16th Street Baptist Church

16th Street Baptist Church is a large, predominantly African American Baptist church on the corner of 16th Street North and 6th Avenue North. It was the target of the racially-motivated 1963 church bombing that killed four girls in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. The church remains and active congregation, while the building serves as a central landmark in the Birmingham Civil Rights District, right across the street from the Civil Rights Institute overlooking Kelly Ingram Park.

16th Street Baptist Church was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006.

Beginnings

16th Street Baptist Church, first organized as the First Colored Baptist Church on April 20, 1873, was the first black church established in the two-year-old city of Birmingham. The first meetings, organized by Reverends James Readon and Warner Reed, were held in a small building at 12th Street and 4th Avenue North. A site was soon acquired on 3rd Avenue North between 19th and 20th Street for a dedicated building.

In 1882 the church sold that property and built a new church on the present site on 16th Street and 6th Avenue North, completed in 1884. They chose a new name reflecting the building's location, following the cue of the former 2nd Colored Baptist Church, which was located several blocks to the South on 6th Avenue and had taken the name "6th Avenue Baptist Church". The new brick and brownstone building was constructed by the respected Windham Brothers Construction Company, but suffered from structural weaknesses from the start. In 1908 the city condemned the structure and ordered it to be demolished.

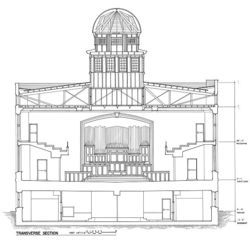

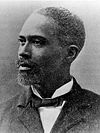

The present building was designed by the prominent black architect Wallace Rayfield was also constructed by the Windham Brothers, and completed in 1911. Differing reports of the cost of construction range from $26,000 to $50,000. In addition to the main sanctuary, the building houses a basement auditorium, used for meetings and lectures, and several ancillary rooms used for Sunday school and smaller groups. Rayfield gave the church a stolid Romanesque style with lightening Palladian and Georgian influences. At the same time, Rayfield and Windham also constructed a parsonage to the immediate left of the church.

As one of the primary institutions in the black community, 16th Street Baptist has hosted prominent visitors throughout its history. W. E. B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune, Paul Robeson, Jackie Robinson and Ralph Bunche all spoke at the church during the first part of the 20th century. The sanctuary also served as one of the largest auditoriums available to the black citizens of Birmingham. Concerts by notable artists such as W. C. Handy frequently animated the building in the evenings.

Civil Rights campaign

- See main article at Birmingham campaign

During the Birmingham campaign of April-May 1963, 16th Street Baptist Church served as a rallying point for African American demonstrators against widespread institutionalized racism in Birmingham. The size and location of the church made it an ideal location from which to send marchers to downtown Birmingham's commercial district, municipal buildings and parks.

In her book Carry Me Home Diane McWhorter recalls that 16th Street Baptist was not a true "Movement church". Revolutionary thinking was actively discouraged from Reverend John Cross' pulpit. The singing was staid and solemn, in contrast to the jubilant gospel that energized poorer congregations. It was, according to her, the only church that charged a fee when its facilities were used by Fred Shuttlesworth's Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights.

In the Spring of 1963, however, Martin Luther King, Jr's stature as the leader of a national non-violent Christian movement helped him to secure the lukewarm support of Cross and John Thomas Porter, pastor of 6th Avenue Baptist Church. The participation of these large middle-class churches pushed the divisions within the black community into the background during the biggest clash between the movement and anti-integrationist forces.

Notably, it was the place where Birmingham's black students were told to meet to launch the Children's Crusade, a last-ditch effort to turn up the pressure on city leaders during the Birmingham Campaign. They held workshops and training sessions to become an organized force that would split into groups to conduct numerous marches throughout the downtown area on May 2-7. With the jails full of demonstrators, Bull Connor launched a counterattack to stop the marches. His order to turn police dogs and fire hoses onto the youthful demonstrators instantly galvanized the consciences of those who had been ambivalent about the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham and across the country.

The mounting tensions escalated into violent clashes between ever-growing numbers of armed law-enforcers, the endless waves of teenagers and children who had joined the organized movement, and the mounting numbers of agitated bystanders drawn into the fight. Pressure to effect a negotiated truce was applied at the Federal level. After several false starts, an agreement to release the jailed demonstrators and begin desegregating businesses and public facilities was announced at a press conference at the A. G. Gaston Motel on May 10.

Bombing

- See main article 1963 church bombing.

This monumental victory for integration was not well-received by Birmingham's organized and violent racist element, particularly the Ku Klux Klan. Several attempts were made on Dr King's life. His brother's house and several churches were bombed during the summer. Tensions mounted as the prospect of school integration approached. On Sunday, September 15, 1963, Bobby Frank Cherry and Robert Edward Chambliss, both Klan members, planted 19 sticks of dynamite and a crude timing device at the base of the church. At 10:22 a.m., the bomb exploded, killing four young girls.

It was one of a string of dozens of officially "unsolved" bombings that had terrorized "uppity" blacks and progressive agitators in the city for more than a decade, but in this case, the taking of indisputably innocent lives shocked the city, the nation and the world. The bombing is credited with helping push forward passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

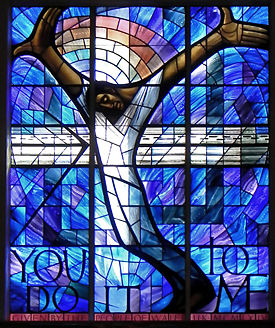

Following the bombing, over $300,000 in unsolicited gifts were received and repairs were begun immediately. The church reopened on June 7, 1964. The Wales Window for Alabama, a stained-glass window depicting a crucified black Christ, designed by the Welsh artist John Petts, was donated by the citizens of Wales and installed in the front window, facing south.

Current status

In 1980, 16th Street Baptist Church was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1993, a team of surveyors for the Historic American Buildings Survey executed measured drawings of the church for archival in the Library of Congress. On February 20, 2006, the church was officially dedicated as a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of the Interior.

As part of Birmingham's Civil Rights District, which is promoted by the city for heritage tourism, 16th Street Baptist Church receives over 200,000 visitors annually. Though the current membership is only around 250, it has an average weekly attendance of nearly 2,000. In addition to greeting visitors and leading tours, members of the church also operate a large drug counseling program. The current pastor is Reverend Arthur Price.

16th Street Baptist Church completed a major restoration of the building in 2008. The first phase of the $3 million restoration project, aimed at eliminating water infiltration below grade, was completed in July 2006. The second phase, which included repairs and restoration of the exterior, was completed in September 2008. That work included the re-creation of the church's historic neon sign and the installation of a memorial plaque at the location of the 1963 bombing. Artur Davis spoke at the dedication service on September 14. The church fell about $700,000 short of their fund-raising goal for the project, leaving interior finishes untouched.

A $500,000 grant from the National Park Service's African American Civil Rights Grant Program, awarded in 2017 with the commitment of $50,000 in matching funds from the City of Birmingham, allowed 16th Street to contract for the restoration of wooden pews and stained glass windows. Another $500,000 grant, awarded in 2018, helped fund the church's third phase of renovations. 16th Street Baptist has also received support from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund to go toward an endowment for long-term maintenance.

In March 2023 the Jefferson County Commission allocated $900,000 of its American Rescue Plan Act funds toward the church's planned visitor and educational building. A $7.5 million campaign to raise funds for construction of that building and ongoing conservation of the church's historic buildings was launched in early 2024.

Pastors

- James Redding and Warner Reed, 1873-1876

- A. C. Jackson, 1876-1882

- William Pettiford, 1883–1893

- T. L. Jordan, 1893-1898

- Charles Fisher, 1898-1910

- J. R. Whitted, 1911-1916

- Alfred C. Williams, 1916-1920

- Charles Fisher (2nd term), 1921-1930

- S. A. Owens, 1930

- A. B. Coleman, 1932

- David Frederick Thompson, 1932-1943

- Luke Beard, 1945-1960

- John Cross, 1962–1967

- James Crutcher, 1968–1982

- Christopher Hamlin, 1990–2001

- Arthur Price, 2001–present

References

Books

- Boothe, Charles Octavius (1895) Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama: Their Leaders and Their Work Birmingham: Alabama Publishing Co. Documenting the American South (2001) University of North Carolina Library

- Branch, Taylor (1988). Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954 -1963, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671687425.

- Corley, Robert G. (1979). The Quest for Racial Harmony: Race Relations in Birmingham, Alabama, 1947-1963, Ph.D. Dissertation, Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia.

- Eskew, Glenn T. (December 1997). But For Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807846678.

- Satterfield, Carolyn Green. (1976) Historic Sites of Jefferson County, Alabama. Prepared for the Jefferson County Historical Commission. Birmingham: Gray Printing Co.

- Fallin, Wilson (July 1997). The African American Church in Birmingham, Alabama, 1815-1963: A Shelter in the Storm, New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 0815328834.

- Hamlin, Christopher M. (April 1998). Behind the Stained Glass: a History of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Birmingham, AL: Crane Hill. ISBN 1575870835.

- Fazio, Michael W. (2010) Landscape of Transformations: Architecture and Birmingham, Alabama. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 9781572336872

Articles

- "From early days blacks bound to the church." (December 19, 1971) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Norris, Toraine (February 17, 2006). "Sixteenth Street Baptist named U.S. landmark." The Birmingham News

- McMillan, Aneesa (July 14, 2006). "Work begins on 2nd phase of renovation." The Birmingham News

- Spinks, Amie A. (November 2004) "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Sixteenth Street Baptist Church." - accessed January 24, 2007

- Garrison, Greg (September 15, 2007) "Sixteenth Street Baptist wrapping up restoration." The Birmingham News

- Garrison, Greg (September 14, 2008) "Sixteenth Street Baptist Church radiates from light of new sign." The Birmingham News

- Garrison, Greg (March 12, 2018) "Sixteenth Street Baptist Church renovation underway." The Birmingham News

- Henderson, Jesse (May 21, 2021) "Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Sunday Worship, Redefining History and Reaching Community" Magic City Religion

- Morris, Williesha (September 10, 2023) "16th Street Baptist celebrates 150-year ‘legacy of resilience’ in Birmingham." AL.com

- Garrison, Greg (February 19, 2024) "Historic 16th Street Baptist Church starts $7.5 million fundraising campaign." AL.com

External links

- 16th Street Baptist Church website

- 16th Street Baptist Church at the Historic American Building Survey

- 3-D model of 16th Street Baptist Church by Jordan Herring