Ban the Beatles

Ban the Beatles was a popular movement against the English rock and roll group, the Beatles, which was provoked by a remark by John Lennon that the group was "more popular than Jesus" and stoked by social conservatives and publicity-seeking radio stations. Tommy Charles and Doug Layton of the upstart Birmingham radio station WAQY-AM are credited with having touched off the movement, which flourished in late Summer of 1966, and has become a key episode in the history of the Beatles' popularity in the United States. The event led the group to suspend touring, and some believe it contributed to their break-up three and a half years later. Details about how the local campaign played out, however, are scarce and sometimes contradictory.

Background

WAQY, referred to on air as "wacky," was founded in 1964 by Bessemer Chevrolet dealer Tom Gloor along with Charles and Layton. It took over the 1000-watt daytime-only frequency formerly used by WEZB-AM and steered its playlists to a milder form of pop music for the segment of the audience that was turned off by the "screaming" and "psychedelic way-out sounds" heard on teen-oriented stations such as the powerhouses WSGN-AM and WVOK-AM.

Meanwhile, in March 1966, John Lennon, was interviewed by a close friend, Maureen Cleave, for a series of lifestyle features in the London Evening Standard. She noted that Lennon was "reading extensively about religion" at the time and quoted him as saying, "Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue about that; I'm right and I'll be proved right. We're more popular than Jesus now; I don't know which will go first—rock 'n' roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me." His words didn't raise much stir in the UK, but the profiles were popular and Beatles publicist Tony Barrow sold the rights to the content to the American teen magazine Datebook, which published them together in their July 1966 issue. The magazine's art editor, Art Unger, ran part of the quote, "I don't know which will go first-rock'n'roll or Christianity," along with other excerpts from the issue on the front cover. (Just above it, on the same cover, was Paul McCartney's quote that "It's a lousy country where anyone black is a dirty nigger!")

WAQY

Charles and Layton usually brought up a current issue to kick off their daily program, hoping to generate a few calls and maybe a little publicity. According to music journalist Paolo Hewitt, it was Layton who first told Charles about Lennon's quote. When Charles read it, he said, "That does it for me. I am not going to play the Beatles any more." They discussed it on their August 4 morning program and heard from numerous listeners who called in, unanimously outraged over the perceived sacrilege.

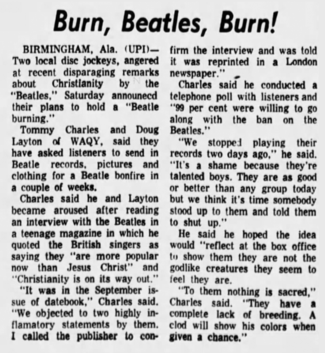

Alvin Benn, a United Press International reporter, happened to hear the show while driving to his office. When he got to his desk he telephoned Charles to get the story. He later recalled in his memoir, "The more he talked, the more I knew it would be something our Atlanta and New York desks would love to get."

An Associated Press report about the campaign launched by WAQY appeared on the front page of The New York Times on August 5 with a Birmingham dateline. It quoted Charles as saying, "We just felt it was so absurd and sacrilegious that something ought to be done to show them they cannot get away with this sort of thing." The report reprinted Lennon's full quote about Christianity and a note that a Beatles spokesman had said the band had no further comment. It ended with the statement that "Several radio stations scheduled bonfires for the burning of Beatles' records and pictures."

As word spread, other stations in the region jumped on the bandwagon. Many of them, which normally played adult standard or country music, were unlikely to have played Beatles records anyway. Louisville, Kentucky's WAKY-FM (also pronounced "wacky") scheduled an hourly 10-second silence for prayer.

In a follow-up announcement on August 8, Charles explained that, "Doug Layton and I are, as you may have heard, leading a protest against the Beatles because of certain anti-Christian and anti-American statements they made which appeared in a national teenage magazine. But, this is your fight, not ours. We are only the leaders. If you, as an American teenager, are offended by statements from a group of foreign singers which strike at the very basis of our existence as God-fearing, patriotic citizens, then we urge you to take your Beatle records, pictures and souvenirs to the pick-up points about to be named, and on the night of the Beatles' appearance in Memphis, August 19, they will be destroyed in a huge public bonfire at a place to be named soon."

Nationwide

Soon news photographers were documenting groups of teens who had gathered with their Beatles materials to be destroyed. Footage showed young people stomping on records and cheering as fires consumed piles of paraphernalia. One such crowd, filmed as they laughed and stuffed a metal trash can with Beatles materials, was gathered at Ralph Fowler's Service Station on 1st Avenue North at 17th Street. Young people in the crowd held signs reading "Beatles Stinks" [sic] and depicting Lennon as the devil, with horns and a goatee.

Reporters around the South gathered interviews from teenagers, ministers and others who expressed varying levels of bemusement or rage over the controversy. One interview with a man wearing a Ku Klux Klan robe, was filmed just outside Memphis' Mid-South Coliseum where the Beatles were scheduled to perform. Grand Dragon Bob Scoggin tossed Beatles records onto the base of a burning cross in Chester, South Carolina on August 11.

Band manager Brian Epstein became increasingly concerned about the possibility of violence during the remainder of the scheduled worldwide tour. Demonstrations against the band were also staged in Mexico City, South Africa, Spain and Japan (where the controversy was focused on the threat to Japanese culture rather than to Christianity). Lennon apologized for the comment, or at least for its perception, in an interview in Chicago, Illinois that same month.

At the urging of Mayor William Ingram, who proclaimed that, "The Beatles will be dead and forgotten, literally and figuratively, in a relatively short time," the Memphis City Council voted to cancel the concerts there, stating that its municipal facilities were not to be "used as a forum to ridicule anyone's religion." Due to contractual obligations, however, the shows went ahead as planned. The evening performance was interrupted by a firecracker thrown onto the stage. Others protests were staged across the country, including the final show at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, California.

The long tour was a strain on the band's members who were eager to spend more time in the studio exploring new sounds than in arenas playing their earlier hits for delirious seas of young fans. The group never again toured the United States. Interviewed in 1968, Lennon referred to the US protestors as "fascist Christians." Ten years later he expressed gratitude for the threats that gave them an excuse to curtail their exhausting touring schedule: ""if I hadn't said [that] and upset the very Christian Ku Klux Klan, well, Lord, I might still be up there with all the other performing fleas! God bless America. Thank you, Jesus." Lennon was murdered in December 1980 by Mark David Chapman, a born-again Christian who referred to the "more popular than Jesus" remark as "blasphemy."

Aftermath

WAQY's promised bonfire never actually took place, perhaps in part because a city ordinance specifically prohibited public bonfires. There are mentions of the station announcing that it would obtain a tree-shredder from the city instead. On August 13, the day after the Beatles performed at International Amphitheatre in Chicago, the Associated Press sent out a story quoting Charles as saying, "We have called off our planned destruction of the Beatle [sic] records and other things we have collected."

It is likely that the bulk of the materials sent to the station were just thrown away. J. Willoughby, son of Layton's later broadcast partner John Ed Willoughby, remembers Layton saying that he "could have made a fortune" from the albums sent to him for destruction. Willoughby also recalled that both Layton and Charles enjoyed the Beatles' music.

References

- Benn, Alvin (July 30, 1966) "Burn, Beatles, Burn!" UPI / Alabama Journal, p. 14

- "Comment on Jesus Spurs a Radio Ban Against the Beatles" (August 5, 1966) Associated Press/The New York Times

- "Ban Called Off" (August 13, 1966) AP / Montgomery Advertiser, p. 11

- Benn, Alvin (2006) Reporter: Covering Civil Rights...And Wrongs in Dixie. AuthorHouse ISBN 9781420861877

- Hewitt, Paolo (2012) Love Me Do: 50 Great Beatles Moments London: Quercus Publishing ISBN 1780873298

- Dean, Charles J. (July 31, 2014) "Do you remember smashing Beatles records 48 years ago today?" The Birmingham News

- Murrmann, Mark (August 12, 2014) "Burn Your Beatles Records!. Mother Jones

- "More popular than Jesus" (April 29, 2015) Wikipedia - accessed May 14, 2015

- Carlton, Bob (July 15, 2015) "Birmingham and Crimson Tide radio legend Doug Layton dies at 81." The Birmingham News

- Willoughby, J. (March 4, 2016) "The Beatles' breakup may have had roots in Alabama." The Birmingham News

- Taylor, Drew (November 30, 2021) "2 Alabama radio hosts started the ‘Ban the Beatles’ movement in 1966." CBS42.com