Gorgas Steam Plant

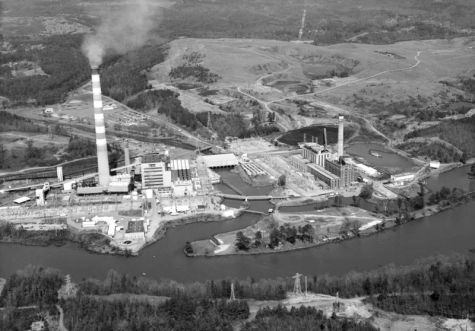

The William Crawford Gorgas Electric Generating Plant, also known as the Gorgas Steam Plant or Plant Gorgas, was a 3-unit, 1 million kilowatt, coal-fueled electrical generation facility located on a 1,250 acre site at the confluence of Baker Creek and the Mulberry Fork of the Black Warrior River in Walker County, near the town of Parrish.

The plant was constructed in 1917 by the Alabama Power Company as the Warrior Reserve Steam Plant. The United States government financed the construction of a second unit at the site in 1918. Alabama Power purchased that unit in 1923 and began construction of a third unit. Upon completion in 1924 the plant was renamed in honor of former Surgeon General of the Army William C. Gorgas, who had testified on behalf of the utility in a series of lawsuits claiming that the construction of Lay Dam was responsible for an outbreak of mosquito-borne illnesses.

Over the years Alabama Power added seven more generating units and opened its own Gorgas Mine to help supply coal to the plant. In order to attract reliable workers, the company paid high salaries and provided free housing, utilities, medical care, schools and recreational facilities in the town of Gorgas.

Until the 1950s, waste products from the plant's operation, including fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, flue gas emission control residuals, and wastewater were discharged directly into the river. A new low-volume wastewater treatment pond, "Rattlesnake Lake", was created by building a stacked-stone dam on Rattlesnake Creek on the opposite bank of Mulberry Fork in 1953. Wastewater from the plant was piped under the river to reach the pond, which at full pool reached a level about 80 feet above the river. It was raised another 55 feet in the 1970s.

In 2002 Alabama Power added selective catalytic reduction (SCR) scrubbers to the plant's stacks, reducing output of a nitrogen oxide, a key contributor to ground-level ozone. In 2006 Plant Gorgas ranked as the seventh most-polluting coal plant in the United States as measured by impounded coal combustion waste. The utility explained that the ranking was best explained as a function of the large capacity of the plant rather than as an issue with its management. An "ash pond improvement project" commenced in 2007. It involved raising the dam by 15 more feet and creating a new relief spillway and upstream slope protections to increase the pond's capacity to 17.3 million cubic yards. Gypsum waste was redirected to a series of lined treatment ponds totaling about 18 acres to the northwest of the plant. New sulfur dioxide and particle scrubbers were installed in 2008. In 2013 a 21-acre lined landfill for gypsum removed from the treatment ponds went into service. That was followed in 2014 by a 33-acre lined for coal combustion residuals (CCR)

In 2015, shortly after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency published new rules requiring the monitoring of groundwater and management of effluent from coal-burning plants, the power company announced plans to close and cover its ash ponds and convert all of its coal-fired plants to dry-storage. Additional work to bring the plant into compliance with environmental laws and regulations was completed in 2014 at a cost of $380 million. Installation of a large "baghouse" intended to capture mercury. Units 6 and 7 were retired in 2015 and disassembled over the next two years. Costs associated with compliance projects were cited in a January 2019 consumer rate increase.

Runoff from the dam is discharged into the Mulberry Fork and is regulated by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management. In 2018 ADEM cited Plant Gorgas along with five other coal-burning electrical plants for, "violating the state's clean water laws by contaminating groundwater," primarily with arsenic. The company was fined $450,000 at each site.

Closure and demolition

Plant Gorgas was shut down on April 15, 2019, prior to the deadlines set by ADEM for submitting reports on the extent and source of groundwater contamination and the proposed measures to remediate the pollution and close the ash ponds. Company officials and members of the Alabama Public Service Commission blamed unnecessary federal regulations for causing the shutdown. Some workers remained on site to close the coal ash pond and secure the site. Alabama Power announced that it planned to recover approximately $740 million in "net investment costs" related to the plant, plus a profit margin, by increasing rates for electrical power consumers.

By 2020 Alabama Power announced that Rattlesnake Lake contained approximately 25,000,000 cubic yards of CCR, while its bottom ash landfill held another 3,800,000 cubic yards, and its CCR landfill held another 60,000 cubic yards. At that time the gypsum pond contained 340,000 cubic yards, and the gypsum landfill had no gypsum or CCR in it. The utility planned to remediate the gypsum pond by removal and its bottom ash landfill by closure in place.

In May 2020 Jackson Demolition of Schenectady, New York won the $44 million contract to demolish the Gorgas Steam Plant structure, plus an additional $9 million contract for site restoration. The top 400 feet of the main 750-foot chimney was dismantled robotically by subcontractor Pullman Services of Columbia, Maryland. Three boiler houses and the remaining vent stack were demolished by implosion by subcontractor Controlled Demolition of Phoenix, Maryland on September 9, 2021. Another subcontractor, Veit Co. of Rogers, Minnesota, was hired to dismantle a large storage building which had been constructed over Baker Creek and a 450-ton barge unloading structure on Mulberry Fork. Jackson salvaged 60,000 gross tons of ferrous metal and 4 million pounds of nonferrous metal for recycling, and reused 15,000 tons of concrete as part of the site fill.

References

- Atkins, Leah Rawls (2006) Developed for the Service of Alabama: The Centennial History of the Alabama Power Company, 1906-2006 Birmingham: Alabama Power Company. ISBN 0978675304

- Sturgis, Sue (January 5, 2009) "Coal's ticking timebomb: Could disaster strike a coal ash dump near you?" Facing South. Institute for Southern Studies

- Snazderman, Michael (July 10, 2015) "Gorgas baghouse nearing completion." Alabama NewsCenter (owned by Alabama Power)

- Pillion, Dennis (September 30, 2015) "Alabama Power expects to close coal ash ponds 'eventually' due to new EPA rules." The Birmingham News

- Pillion, Dennis (March 2, 2018) "Alabama Power fined $1.25 million over coal ash ponds." The Birmingham News

- Pillion, Dennis (December 6, 2018) "Alabama coal ash ponds do not meet EPA groundwater rules, must permanently close." The Birmingham News

- Pillion, Dennis (January 4, 2019) "Alabama Power blames rate increase on coal ash costs." The Birmingham News

- Pillion, Dennis (February 20, 2019) "Alabama Power to shutter coal plant, cites environmental laws." The Birmingham News

- Howell, Ed (February 21, 2019) "Gorgas plant closing April 15 after 102 years." Daily Mountain Eagle

- Pillion, Dennis (March 3, 2019) "Alabama Power customers to pay $740 million after coal plant closes." The Birmingham News

- "Alabama Power, project partners implode retired Plant Gorgas structures." (September 9, 2021) Alabama NewsCenter (Alabama Power Co.)

- Gaetjens, Bob (July/August 2022) "Breaking down big demo jobs: With a tricky site and 250 assets to consider, Jackson Demolition’s careful planning got the job done at Plant Gorgas in Alabama." Construction & Demolition Recycling

External links

- Aerial photographs of Plant Gorgas for the Historic American Engineering Record (Jet Lowe, 1994)