Selective Buying Campaign

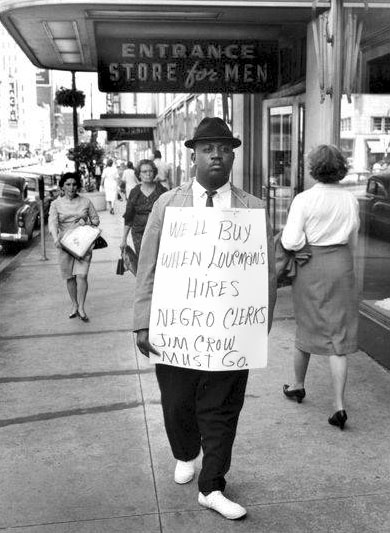

The Selective Buying Campaign was a non-violent demonstration organized by local college students to pressure Birmingham merchants to desegregate their stores and begin hiring African American clerks. The campaign, modeled after the Montgomery Bus Boycott, aimed to make visible the economic power of black shoppers. It was conducted in March-June 1962, and again in advance of the Birmingham Campaign in the Spring of 1963, timed to coincide with Easter shopping season.

The initial campaign was planned by student leaders from Miles College, Daniel Payne College, Booker T. Washington Business College and Birmingham-Southern College. The students, led by Korean War veteran and Miles College student Frank Dukes and faculty member Jonathan McPherson formed an "Anti-Injustice Committee" (AIC). The committee drafted a list of demands which included the desegregation of public buildings and businesses and the hiring of African Americans in stores and government departments. Dukes and his committee met with Sidney Smyer, James Head, Emil Hess, Roper Dial and other white business leaders. Those meetings proved unproductive, so the committee began planning a public demonstration.

Dukes approached the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce for information on department stores "for a school project". He learned that merchants operated on about a 12-15% margin while black shoppers accounted for about 25% of sales. Because "boycotts" as such were illegal, The AIC published leaflets proposing "selective buying" as a form of demonstration, knowing that if they caused a 50% decrease in black spending, that the stores' profits would vanish. The group coordinated closely with the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and was advised by its founder, Fred Shuttlesworth. It was also advised by Miles president Lucius Pitts.

In addition to attempts to enlist public participation, the campaign relied on its leaders to picket on the streets, confronting black shoppers who were ignorant or unsupportive of the campaign. In a few instances, demonstrators publicly shamed consumers into returning items already purchased, or even seized merchandise and tossed it back into the store or otherwise damaged it. Those instances were exaggerated by rumor and the threat of confrontations kept many people, both black and white, away from downtown stores during the campaigns.

The effect of the coordinated actions was great, with some stores reportedly experiencing as much as a 40% decline in profits. Several stores made token efforts to comply with the demands of the campaign leaders by removing "whites only" signs from drinking fountains, dressing rooms, restrooms and elevators. None hired African American clerks, however. The Birmingham City Commission reacted swiftly to merchants it deemed in violation of the city's segregation ordinances, however, and threatened to revoke the stores' business licenses.

The campaign had a secondary effect of increasing awareness of organized resistance to segregation and injustice. It provided a precedent for successful public demonstrations and did succeed in demonstrating, to an extent, the real economic influence of the black community. Dukes and other AIC members participated in the plans for large-scale nonviolent protests conducted by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in April 1963. Dukes served as a campus organizer, march leader and security guard during that campaign.

References

- Dukes, Donna (January 28, 2015) "Trying to Grasp a Force of Nature: The Selective Buying Campaign of 1962" The Struggle Continues