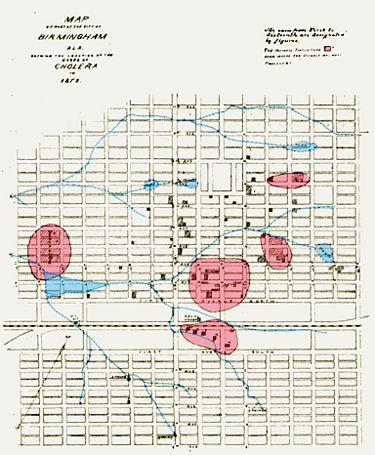

1873 cholera epidemic

The Cholera Epidemic of 1873 afflicted several cities in the Southeastern United States. This outbreak began in Memphis and moved along rail lines to Nashville, Huntsville, Birmingham, and Montgomery. Birmingham was particularly hard hit by the illness due to the lack of urban infrastructure and the poor housing conditions of many citizens. At least 128 people died from cholera, which struck in the height of summer and persisted for several weeks. The outbreak caused about half of Birmingham’s 4,000 residents to flee the city. The effect of the disease combined with a subsequent national financial panic to threaten the survival of the "Magic City".

Outbreak

The disease was first introduced to Birmingham from Huntsville. The first patient, who had been in the city for weeks, became ill on June 12, three days after taking receipt of his bedding, shipped to him from Huntsville, where it had been used in a disease-stricken area. He died within 24 hours of taking sick. The attending physicians did not at first diagnose cholera, and no care was taken to disinfect his bedclothes, which were discarded behind the house. The next cases, two young sisters of the Hughes family, whose members had visited the house of the first patient, also died quickly, with their effects also discarded carelessly into a marshy branch behind their house which fed into a basin on the edge of the "Baconsides" quarter of shanties.

Baconsides became the primary incubator for the disease in Birmingham as its refuse flowed into the same basin in which infected clothing and bedding were washed, and from which water was taken up in barrels for use around the city. Frequent rain showers and summer heat contributed to the climate in which the disease rapidly spread across the city. After a community-wide Fourth of July celebration in Blount Springs, the outbreak became general.

Recovery

While the African American community would remain the hardest hit, the illness moved rapidly through the rest of Birmingham. City leaders ordered that the town bell, which had rung for deaths, no longer be used as its tolling was too frequent and too distressing. Many residents left the city at this point fearing for their health. Fortunately, the epidemic became milder over time and did not spread to Mobile or New Orleans.

Doctor Edward A. Semple of the Alabama Board of Health had organized a corps of nurses to be sent by train from Montgomery to Birmingham in July. However, after Semple received a letter from Mayor James Powell on July 15 stating that, "the cholera is abating rapidly and no new cases reported last night," the nurses were not sent. For the same day, a source credited as, The Birmingham News]] was quoted as printing the following:

"That our opinions in regard to the sickness in this city have been apparently contradictory, is an evidence we have been trying to give correct reports. One day we say the cholera is abating, the next day the mortality report is increased, and we advise people to keep away. This has been the experience of every one who has watched the progress of the epidemic—the hopes of one day have been disappointed by the reality of the next. For the last forty-eight hours the cholera has been very bad and the mortality truly fearful; yet we believe the crisis is over, and that those who have remained in the city had better stay here. With ordinary prudence they are, in our opinion, in no danger. We advise absentees, though, to keep away."

On July 18 the News reported that, "We are authorized by the Board of Health to say there has been no death, nor any case of cholera in the city for the past twenty-four hours."

There are numerous stories of personal courage during this period. Many medical professionals stayed to tend to the sick despite the risk to their own health. Other residents contributed by sharing their private wells and rain cisterns with the community. The News singled out Father John McDonough of St Paul's Catholic Church and Reverend Thomas Davenport of First Methodist Church as the only clergymen who remained in the city, which then boasted six churches. Davenport sent out an appeal for monetary contributions One of the most popular local tales involves Louise Wooster, a local prostitute, who, along with her associates assisted in caring for the sick during this period. Some of these individuals wrote accounts of their experiences during this time.

Physician James Luckie remained in the city through the course of the outbreak, treating the stricken. He himself became the last person reported to have contracted cholera during the outbreak. Fellow physician Mortimer Jordan Jr took Luckie under his own care, and, as secretary of the Jefferson County Medical Society, assumed charge of investigating the course of the epidemic in Birmingham. Afterward he submitted a written report to the Surgeon General of the United States.

Birmingham’s Oak Hill Cemetery contains the grave sites of many of the victims of the cholera epidemic, along with those who cared for them.

References

- "Local Intelligence" (July 16, 1873) Montgomery Advertiser and Mail, p. 3

- quoted in The West Alabamian (July 23, 1873), p. 3

- Jordan, Mortimer H. (August 1874) "Cholera at Birmingham Alabama in 1873", published in The Narrative of the 1873 Cholera Epidemic (1875) Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, pp. 410-414

- Caldwell, H. M. (1892) History of the Elyton Land Company and Birmingham Alabama. Birmingham: Birmingham Printing Company

- Luckie, Mrs. (n. d.) Sketch of the 1873 Cholera Epidemic. On reserve in the Birmingham Public Library Archives in the Ferguson Collection.

- Means, T. A. (1875) Report of a Case of Epidemic Cholera Which Occurred at Montgomery, Alabama in 1873. The Narrative of the 1873 Cholera Epidemic. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office

- Wooster, L. C. (1911) Autobiography of a Magadalen. Birmingham: Birmingham Printing Company.

- Sulzby, James F. (1945) Birmingham Sketches from 1872 through 1921. Birmingham: Oxmoor Press

- Rosenberg, Charles. (1962) The Cholera Years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Norton, Bertha Bendall (1970) Birmingham's First Magic Century: Were You There?. Birmingham: self-published/Lakeshore Press

External Links

- Birmingham Cholera Epidemic of 1873. (August, 1874) Report and map by Mortimer Jordan Jr.