Birmingham Terminal Station

- This article is about the demolished train station. For the demolished MAX bus terminal, see Birmingham Central Station.

The Birmingham Terminal Station was the primary passenger station for Birmingham from 1909 to the 1950s. It filled two blocks of 26th Street North (now Carraway Boulevard) above the 5th Avenue North underpass.

The station was constructed and operated by the Birmingham Terminal Company, a subsidiary of the Washington D.C.-based Southern Railway, which operated several passenger trains serving Birmingham. During the heyday of rail travel in the 1920s to the early 1950s, the Terminal Station served as the primary arrival point for out-of-town visitors. As automobile and air travel came in to prominence in later years, the building was neglected. It was finally torn down in 1969 to prepare the site for redevelopment for a planned federal office complex. After those plans fell-through the vacant site was eventually used as part of the route of the Red Mountain Expressway.

History

In the early 20th century, Birmingham was served by seven railroads. Six of these joined together to form the Birmingham Terminal Company which set out to develop a landmark passenger station. Acquiring property for the project, the company purchased First Congregational Christian Church and other parcels in 1905.

The company hired Atlanta architect P. Thornton Marye, who would also design Highlands Methodist Church, to prepare plans for a majestic structure. His design was inspired by Beaux-Arts and Byzantine precedents. In 1956 architectural historian Carroll Meeks described Birmingham's station as one of a group of "Burnham Baroque" edifices displaying the influence of World's Fair architecture. The exotic architectural style was somewhat controversial at the time. The Oliver-Sollitt Company of Chicago, Illinois won the contract to construct the station building.

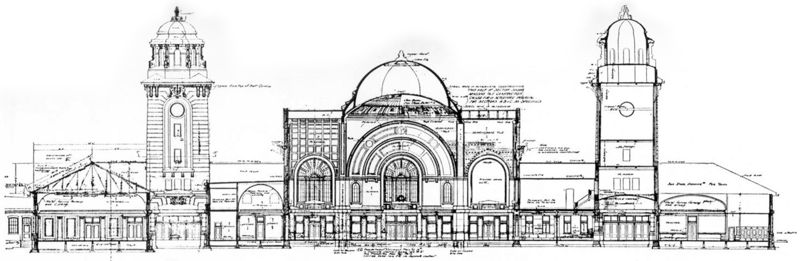

The exterior of the building was primarily brick. Two 130-foot towers topped the north and south wings of its 720 foot length. The central waiting room covered 7,600 square feet and was topped by a central dome 64 feet in diameter reaching 96 feet in height. The dome was constructed using the Guastavino system of layered terra-cotta tiles. At the top of the dome was a skylight of ornamental glass, lit from the openings in the cupola above. The bottom 16 feet of the walls of this main waiting room were finished in gray Tennessee marble.

Connecting to the main waiting room were the ticket office, a separate ladies' waiting room, a smoking room, a barber shop, a news stand, a refreshment stand, and telephone and telegraph booths. Along the north and south concourses were the kitchen, lunch and dining rooms, another smoking room, restrooms, and a 5,200 square-foot "colored" waiting room. The north wing housed two express freight companies while the south was used for baggage and mail transfer.

Outside of the station were ten tracks, designed to accommodate 44 daily passenger trains. A series of overlapping "umbrella" sheds covered the 20-foot wide platforms, with taller sections spanning the tracks. The arrangement provided protection from the rain while still letting in sunlight and fresh air through 10-foot tall openings with 5-foot deep overhangs. Rainwater was conducted through internal drains to subsurface pipes. The exterior platforms and sheds were constructed by the Southern Ferro-Concrete Co..

The station's construction took two years and cost $2 million, approximately $250,000 over budget. The first train to stop at the new platform, nearly two years before the station building was completed, arrived on the evening of June 30, 1907. Station master Lee C. Jones oversaw the first use of the telephone block signal system that guided the Southern Railway train to the south platform at 10:50 PM.

On May 30, 1908 the Illinois Central Railroad line connected Birmingham to Chicago by extending the existing service from Jackson, Tennessee. A large crowd was present for the historic event.

The grand opening of the Terminal Station building occurred on April 6, 1909. A balloon race and a parade, led by Grand Marshal E. J. McCrossin, were held to celebrate.

In 1926 a giant electric sign was erected outside the station at the west end of the underpass. Originally reading "Welcome to Birmingham, the Magic City," it was later shortened to just "Birmingham, the Magic City." It deteriorated over the years due to lack of maintenance and was torn down in 1952, partly because the railroad station was no longer the primary entrance for visitors to the city. City Commissioner James Morgan recommended purchasing smaller signs to place at roadways and the Birmingham Municipal Airport.

During the Depression, the station fell into disrepair, but in the late 1930s it again became an important transportation hub for the area and continued to be so through World War II. In 1943 the station got a $500,000 renovation which included sandblasting, new paint, and new interior fixtures. During this period of rebirth, rail traffic peaked at 54 trains per day. Rail continued as the primary form of long-distance transportation in America through the early 1950s.

Railroad service

Birmingham's Terminal Station was used by the Central of Georgia Railroad, Illinois Central Railroad, St Louis-San Francisco Railway, Seaboard Air Line Railroad and Southern Railway.

Major named passenger trains included:

- Central of Georgia and Illinois Central:

- City of Miami, between Chicago, Illinois and Miami, Florida

- Seminole, between Chicago, Illinois and Jacksonville, Florida

- St Louis-San Francisco and Southern Railway:

- Kansas City-Florida Special, between Kansas City, Missouri and Jacksonville, Florida

- Sunnyland, between Memphis, Tennessee and Atlanta, Georgia

- Southern Railway:

- Birmingham Special, between New York City and Birmingham

- Pelican, between New York City and New Orleans, Louisiana

- Southerner, between New York City and New Orleans, Louisiana

Desegregation suit

In December 1956 Carl and Alexinia Baldwin tested the station's compliance with an Interstate Commerce Commission ruling banning segregation among interstate passengers and were arrested on charges of disorderly conduct which were later dismissed. In January 1957, the Baldwins brought a lawsuit against the Birmingham City Commission, the Alabama Public Service Commission, and the Birmingham Terminal Company to desegregate the waiting rooms in Terminal Station. U.S. District Judge Seybourn H. Lynne dismissed the suit saying it was hypothetical.

As a result of that ruling, Fred and Ruby Shuttlesworth again challenged the segregated waiting rooms at the station on March 6. Having announced their intentions in advance, a heavy police guard was present and despite drawing a crowd of angry whites, the couple were able to board their train without incident. However, Lamar Weaver, a white integrationist who had greeted them in the station, was assaulted after being forced to leave the station by police before he could escape in his car.

The Baldwins' case was later appealed to the Fifth Circuit United States Court of Appeals and reversed in January 1958, sending it back to Judge Lynne. In November 1959 he again dismissed the case saying that none of the defendants were "denying or threatening to deny Negroes equal privileges". Appealed again, the Court of Appeals in February 1961 declared that segregation at the station was "in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and the civil rights act," and ordered the District Court to remedy those practices. Judge Lynne therefore enjoined the three organizations from requiring or even compelling segregation based on race at the station.

Decline and demolition

As automobile ownership increased and air travel gained popularity, rail travel suffered. By 1960 only 26 trains per day went through Terminal Station. As early as 1962 the Terminal Station site was being proposed for redevelopment. Mayor Art Hanes and the Birmingham City Commission offered adjacent city-owned land as part of a proposal to construct a $10 million U.S. Postal Service bulk mail handling facility on the terminal site. In that instance, postal officials determined that relocating track and train facilities would be too expensive. By the beginning of 1969 only seven trains still served the station daily.

William Engel of Engel Realty approached Southern Railroad, then the last remaining partner in the Birmingham Terminal Company and sole owner of the station, with plans to demolish the obsolete building and redevelop the site, with a new, smaller passenger station occupying part of the north end. Those plans were generally unknown to the public, as well as to city officials, until the Terminal Company made application to the Alabama Public Service Commission to declare the facility unnecessary and issue a permit for demolition.

That action by the railway prompted some outcry. The Heart of Dixie Railroad Society, the Alabama Historical Society, the Women's Committee of 100, and a few local architects made public appeals to preserve the building. The Railroad Society's Gilbert Douglas was quoted as saying "Birmingham didn't have much by the way of history to start with, and even though some people look upon the building as a monstrosity, it could be a major tourist attraction." Warner Floyd of the state historical society concurred, estimating the the station represented "20 percent of the architectural heritage assets of a city of three-quarters of a million people."

On June 30, 1969, the Public Service Commission held a public hearing at their Montgomery offices. Acknowledging the pleas for historical preservation, the commission stated that, "their authority is limited by law to consider only the convenience and necessity of the traveling public." (Beiman–1969) They also indicated that objections raised by railway craft unions had been resolved by the Terminal Company's assurances that employee rights would be protected.

Engel also appeared at the hearing, at which time he announced that the site would be used for a $10 million federal office plaza, incorporating two large office buildings and a new motel, along with a smaller passenger station. One six-story building would house a consolidated service center for the U.S. Social Security Administration with a 1,200-space parking lot adjoining it. Engel estimated that the project would create about 3,000 jobs. The commission voted to approve the demolition permit.

The T. M. Burgin Demolition Company began demolishing the station on September 22, although the main terminal platform was maintained until the new, smaller terminal building was built nearby. By December the station's land was completely cleared. Expressing regret for the loss afterward, Mayor George Seibels said, "We just didn't have enough information to try to coordinate the various interests that would have had to come together to save it."

Meanwhile, Engel's deal with Southern Railroad was never completed because another developer, Franklin Haney of Chattanooga, Tennessee, won the contract for a new Social Security Administration building, which was completed in 1974 on the north side of 11th Avenue North, between 19th Street North and 21st Street North.

Legacy

The open land where the Terminal Station once stood eventually solved another problem for the city. The original plans for the Red Mountain Expressway would have involved the destruction of 100 to 150 apartments in the Central City Housing Project (now the site of the Park Place Hope VI project). With the station gone, the expressway route was pushed slightly eastward, avoiding the projects. The portion of the expressway going through the former Terminal Station property was not built until the late 1980s.

A 7.32-acre section of the former station site lying to the east of the expressway was put on the market by Norfolk Southern in 2011 with an asking price of $2.7 million.

The Terminal Station's destruction is now often used as a rallying cry for local preservation groups. Whenever an historic Birmingham structure is threatened, those involved in trying to preserve it often point to the Terminal Station as an example of what Birmingham has lost in the past.

A temporary exhibition on the Birmingham Terminal Station's history, curated by Marvin Clemons, was on display at the Vulcan Center in late 2019. As part of the exhibit, retired engineer and model railroader Gene Clements constructed a 1:48 (O scale) model of the building.

A former Western Union clock from the Terminal Station, owned by Randy Adamy, is displayed at O'Henry's Coffees in Homewood.

A photograph of the station appears in perforated metal panels installed in 2015 on the south wall of the Birmingham National Garage adjoining Jemison Flats, facing Morris Avenue. A mural depicting the Terminal Station was painted on the side of Saab Tire & Automotive by Stephen Smith in 2018.

References

- "First Train Will Steam Into the Big New Terminal Station at 10:50 P.M." (June 30, 1907) The Age-Herald

- J. M. K. (July 11, 1907) "A Splendid Terminal". Manufacturer's Record. pp. 815-816

- Marye, P. Thornton (July 14, 1909) "The New Terminal Station, Birmingham, Ala." The American Architect. Vol. 96, No. 1751 - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Index of Railway Stations" (December 1954) Official Guide of the Railways. Vol. 87, No. 7, p. 1276

- "Terminal Station Is Desegregated By Court Order". (April 25, 1961) Birmingham Post-Herald

- "Terminal site too small, post office officials decide." (May 1962) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Rewound

- Richardson, Charles (January 13, 1969) "Terminal awaits last `all-aboard'". The Birmingham News

- Hobson, Elaine (June 26, 1969) "Committee Seeks To Save Terminal". Birmingham Post-Herald, p. 19

- Beiman, Irving (June 30, 1969) "$10 million multi-story building proposed for Terminal Station site." The Birmingham News, p. 1

- Edge, Lynn (July 2, 1969). "Terminal Station hailed in 1909 as desire fulfilled". The Birmingham News

- Gallups, Jerry (September 22, 1969). "Doomed Station Awaits The Ball". Birmingham Post-Herald

- Kelly, Mark (May 28, 1998) "Terminated Station: The Rise and Fall of Birmingham's Terminal Station". Black & White, pp. 14-17

- Clemons, Marvin and Lyle Key (2007) Birmingham Rails: The Last Golden Era from World War II to AmTrak. Birmingham: Red Mountain Press ISBN 9780615143538

- Morse, Suzanne W. (2009) "The One That Got Away" in Smart Communities: How Citizens and Local Leaders Can Use Strategic Thinking to Build a Brighter Future. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0470435461 , pp. 153-56

- Gray, Jeremy (October 17, 2018) "How Birmingham's iconic Terminal Station was lost to a wrecking ball in 1969." The Birmingham News

External links

- Birmingham Terminal Station (Ala.) collection at Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Proposal for Virtual Preservation of Historic Architecture website by D. Lee Cox

- "A confrontation at Terminal Station" narrated slideshow of Fred Shuttlesworth's protesting of segregation at the station at al.com