Old Town Uptown

Old Town Uptown was the name for the entertainment district carved out of several blocks of Morris Avenue between 20th and 25th Streets in the 1970s.

In 1965 the concept of making the downtown section of Morris Avenue into a protected historic district was presented as one of the recommendations of the "Design for Progress" created by Harland Bartholemew & Associates of Atlanta along with the Birmingham League of Architects. That same year, Bob Moody came to Birmingham to work for Charles H. McCauley & Associates architects and became interested in the possibility of redeveloping the street as an entertainment district.

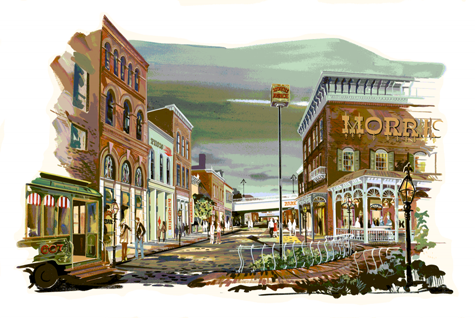

After visiting Gaslight Square in St Louis, Missouri and Underground Atlanta in Atlanta, Georgia, Moody spent two weeks in 1969 researching and sketching concepts, which he began showing to friends. Southern Living executive Roger McGuire encouraged him, and recruited a Chicago developer to come and offer advice. They got McCauley and Charles Snook interested enough to foot the bill for an economic study of the project's feasibility. Other downtown promoters like Temple Tutwiler, James Head, and Ferd Weil encouraged them.

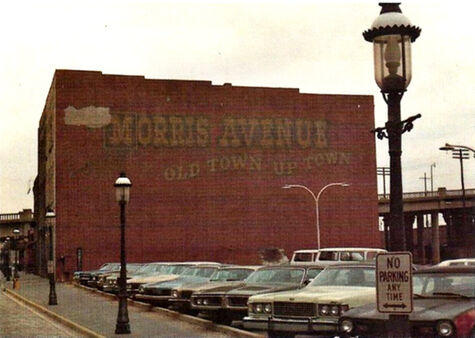

In 1970 Moody organized a presentation at the Parliament House for the owners of the 60-plus properties that could be included in the district. He issued "Morris Bucks" to the majority of them that granted 30-day options to lease the mostly-vacant space to operators. With support from the public, from downtown promoters, and from property owners in the district, the project earned support from Birmingham City Hall, which was anticipating demand for new entertainment options with the opening of the new Birmingham-Jefferson Civic Center. The city spent $1.2 million on streetscaping and other improvements, including cobblestone pavers, textured-concrete sidewalks, and gas-burning light fixtures. They also paid signpainter Neal Snow to paint "Morris Avenue Old Town - Up Town" on the side of the Lacke Building, facing 20th Street.

Meanwhile State legislator Richard Dominick sponsored legislation allowing Morris Avenue to be recognized as the state's first registered historic district. The district was created in 1972 by the Jefferson County Historical Commission and on April 24, 1973 the downtown section of Morris Avenue and 1st Avenue North, between 21st and 24th Streets, became the first site in Birmingham to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Historical Commission took charge of reviewing proposed changes to the exteriors of buildings.

The first businesses began opening in the district in the Summer of 1972, led by Diamond Jim's, Oaks Street and Victoria Station. The development as a whole was given a grand opening celebration on October 15. Despite Moody's vision for a 24-hour business district with a variety of shops and family fare, most property owners opted for higher-profit bar and restaurant tenants. A tourism study by Herdman & Stuckey Travel Investment Corporation projected that 59% of the initial visitors to Morris Avenue would be tourists from outside the area, increasing to 76% after the first six months. Gross income of $800,000 for 100,000 leasable square feet per month was projected by December of the district's first full year.

The district, while popular, proved vulnerable to bad word-of mouth. On August 18, 1977, Nigel Harlan, a Chicago steel executive, was lured into a robbery/murder while unwinding at the Show-Boat Lounge. His body was found in Shelby County three weeks later. A Florida couple was arrested and charged with the killing. The sensational nature of the crime has been blamed for crippling the viability of the fledgling entertainment district.

1978 rejuvenation effort

Am effort to rejuvenate the lagging district was led in 1978 by Richard Mansfield-Jones, whose $18,000 salary was split between the city, the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, and property owners. He acknowledged that the first attempt at creating a lively district "suffered from poor planning, mismanagement, underfinanced investors, poorly promoted parking and a lousy security image."

He took his inspiration not from Gaslight Square, which he criticized for tackiness, but from the the success of another St Louis development, Laclede's Landing. There a redevelopment corporation successfully established a 12-block multi-use historic district with offices and specialty shops. It was hoped that with good planning and investment, the avenue could be reinvigorated and extended, along with trolley service, to a proposed public park at Sloss Furnaces, and by "people movers" or shuttle buses to the Birmingham-Jefferson Civic Center.

At the time, the Alabama School of Fine Arts was proposing to see federal funds for a series of sculpture parks and art shops on Morris Avenue. Metro Bank also discussed the possibility of opening retail shops on the street, and a "mini-mall" was under consideration for the buildings then occupied by the Liberty Trouser Co.

The only public investment to be realized as part of that campaign was a $45,000 refurbishing of the area below the 22nd Street Viaduct into an "piazza".

Later years

Entertainment options on Morris Avenue steadily dwindled, with venues like the Eclectic Theatre, Old Town Music Hall, and Cobblestone bringing intermittent late-night crowds. Only Victoria Station and the long-standing Peanut Depot survived into the 21st century, and were joined briefly by Matthew's Bar & Grill. Most of the buildings on Morris Avenue were redeveloped as professional offices and loft residences. Many are opened during the annual Art Walk festival.

Another revival occurred with the opening of Carrigan's Public House in 2013, construction of the Row5 townhouses in 2017, and several mixed use projects such as Founders Station in 2018, Mercantile on Morris in 2021, and the Armour & Co. building in 2022. The latter three, notably, made explicit connections between Morris Avenue and 1st Avenue North.

References

- Nix, Charles (March 1970) "L&N, city square off to do battle for historic Morris Ave." The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Rewound

- Moody, Bob (October 15, 1972) Morris Avenue Gazette broadsheet

- "Historic register listing boosts Morris Avenue showplace plan." (May 16, 1973) The Birmingham News - via [[Birmingham Rewound]

- Century Plus: A Bicentennial Portrait of Birmingham Alabama 1976 (1976) Birmingham: Birmingham Chamber of Commerce/Oxmoor Press

- "Morris Avenue to be dedicated as historic place June 19." (May 1976) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Rewound

- White, Marjorie Longenecker (1977) Downtown Birmingham: Architectural and Historical Walking Tour Guide. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society.

- Kennedy, Harold (September 2, 1977) "'Mystery man' suspect hunted in Harlan case." The Birmingham News

- Nesbitt, Jim (July 29, 1978) "Morris Avenue–will it make it?" Birmingham Post-Herald, p. C1

- "Morris Avenue part of national trend" (July 29, 1978) Birmingham Post-Herald, p. C1

- Barber, Dean (December 12, 1993) "Night life will return." The Birmingham News

- Archibald, John (September 28, 1997) "Morris Avenue reborn: The one-time entertainment district is again teeming with activity, now as offices and residential lofts." The Birmingham News