Operation Pride

Operation Pride was a federally-funded housing code enforcement program launched in Birmingham's Druid Hills, Fountain Heights and Norwood neighborhoods in 1966. It was the first implementation of a new kind of "urban renewal", one that aimed to eliminate substandard housing by encouraging existing property owners to make their own improvements.

To that end, the program administered funds from the Renewal Assistance Administration of the Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide low-interest loans or grants for home improvements and to contract for the construction and repair of curbs, gutters, sidewalks, street lights and traffic signals in an effort to reverse a trend of urban decline.

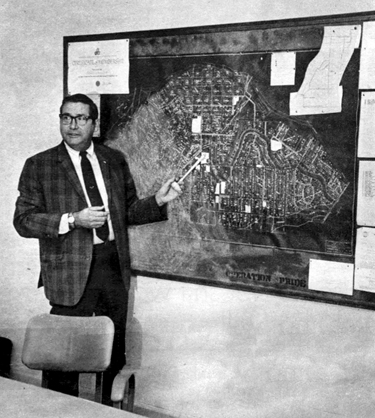

In addition to providing incentives for improvements, the agency, operating on behalf of the Jefferson County Health Department, was also charged with enforcing the city's "Minimum Housing Ordinance", which provided that all residential properties would either have to be brought up to standard or condemned and demolished. Despite a delay in accessing funds, by 1969 director Robert Reese could report that of the 3,091 residential structures in the project area, 300 were found to already be in compliance, 1,100 had been brought up to code, 300 were in the process of being improved, 97 were vacated and 88 more were demolished. In accomplishing this milestone, $2 million had been spent by property owners on improvements and another $2.6 million in new construction had taken place. The agency issued 219 warnings of legal action, but had brought only eight cases to court.

Nevertheless, many area residents, beset by fears of the effects of racial integration, resented the portrayal of their neighborhood as substandard and perceived federal involvement as a threat. Some property owners agreed to make improvements, but refused the financial incentives offered by Operation Pride. The agency was frequently portrayed as part of a concerted effort to integrate the neighborhoods in which it operated. Others judged that the neighborhood was doomed anyway and that the improvements were a waste of money and an unnecessary impediment to the expected change to commercial and industrial uses.

More specifically, the program was criticized for pushing certain contractors on residents at inflated prices—a charge which Reese denied, saying that some unethical contractors misrepresented themselves to residents and that the agency had driven them out.

The program was set to expire in December 1970.

References

- "Operation Pride: Carrot & Stick" (December 7, 1969) In Dixieland (Birmingham News magazine), pp. 8-9 - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections