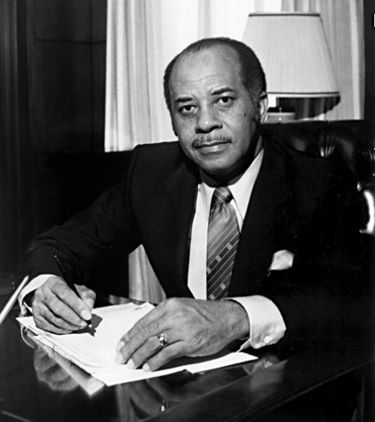

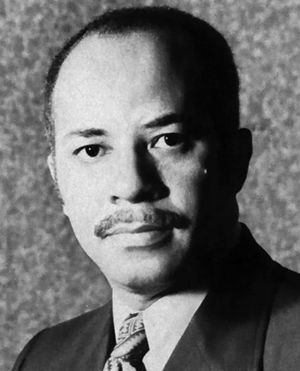

Richard Arrington

Richard Arrington Jr (born October 1934, Livingston, Alabama) was the first African-American Mayor of Birmingham, serving 20 years, from 1979 to 1999. He replaced David Vann and, upon retiring after five terms in office, installed then-City Council president William Bell as interim mayor. After a short term, Bell went on to lose the next election to Bernard Kincaid.

Childhood

Arrington's father moved his family to the steel-town of Fairfield from rural Sumter County when Richard Jr. was five years old, to take a job with U.S. Steel. The steady work was an improvement over sharecropping, but Richard, Sr. still had to supplement the family income by working off-hours as a brick mason.

Arrington's parents emphasized self-reliance, choosing to rent a home rather than stay in workers' housing and shopping at a black-owned cooperative store rather than accept credit at the company commissary. Richard's mother, Ernestine, kept the table filled with home-grown vegetables and made sure that her children made use of the opportunities given them through church and school.

Arrington, while still a teenager, served as secretary of the Sunday School at Crumbey Bethel Primitive Baptist Church. Soon he was Sunday School superintendent, a member of the choir, and eventually elected to the Board of Deacons. He was also a standout student at Fairfield Industrial High School, where he had first decided to study tailoring. With those classes full, he instead learned dry cleaning, graduating in 1951 at the age of 16. Afterwards, he took a job at a cleaner and applied to Fairfield's Miles College.

Academic career

Arrington majored in biology at Miles and excelled in the classroom and as a leader, rising to the presidency of his chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. He was also an officer in the Honor Society and the Thespian Club. In his third year of college, while still living at home, he married Barbara Jean Watts. He graduated cum laude in 1955 and took a position as a graduate assistant at the University of Detroit. While there, he first experienced an integrated social environment and gained the perspective necessary to effectively critique the established segregation of his home town. He earned a master's degree in 1957 and returned to Miles as an assistant professor of science where he taught for six years before entering the University of Oklahoma doctoral program in zoology in 1963. He was, therefore, absent from Birmingham during the most violent clashes between African-American protesters and city authorities in Birmingham. His own account of the period stated flatly: "[I] was never never directly involved, never participated in a single demonstration." Instead, he immersed himself in his studies.

Arrington earned his doctorate at Oklahoma in 1966, completing a dissertation on the "Comparative Morphology of Some Dryopoid Beetles", and, at the urging of Miles president Lucius Pitts, returned to Fairfield as acting dean and director of the Miles College summer school. He was quickly promoted to chair of the Natural Sciences Department and was eventually named Dean of the College.

Political career

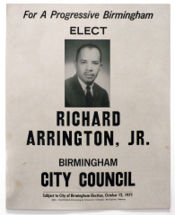

In 1971, Arrington was invited by a group of young African-Americans to consider running for mayor of Birmingham. He declined, but did agree to run for City Council. During his campaign, he pledged to make Birmingham "a city of which all her people can be proud." He campaigned with the endorsement of the Progressive Democrats of Jefferson County, his funding came primarily from white supporters of Miles College. In the general election, he placed third among 29 at-large candidates. He came about 3,000 votes shy of avoiding a run-off in an election where as many as 16,000 votes were invalidated, mostly from African-American precincts.

In the run-off, Arrington faced five opponents for three remaining seats. He won his seat easily, becoming, the first African-American elected to that office in Birmingham. Attorney Arthur Shores was the first to take a seat in the Council, but had been appointed to a vacant seat by George Seibels in 1968.

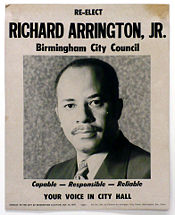

Arrington was elected chair of the Council's Transportation and Communication Committee. After two years of quiet service, he introduced an ordinance requiring city departments to formulate hiring plans that included affirmative action goals and to contract business to companies that hired minorities. With opposition from the business community, the latter action failed, but the departmental hiring ordinance made it out of council to be vetoed by Seibels. Revised proposals that established recruitment programs and prohibited contracting with openly discriminatory firms were later passed. His next major controversy was to push for a formal investigation of the shooting of an African-American suspect while he was under police custody. The hearing was inconclusive, but opened the door to a more serious look at police procedures. Arrington's perseverance in exposing police brutality, a cause Arrington was involved in through the Community Action Committee before entering politics, had a galvanizing effect. It solidified his support in the black community while angering business interests that wished to avoid more negative publicity for the city.

It was arguably an instance of such brutality, however, that opened the door for Arrington to challenge David Vann for the mayor's office. Vann's incapacity to satisfy the demand for swift action following the fatal police shooting of Bonita Carter, an unarmed 20-year-old woman near the scene of a convenience store robbery left him vulnerable. Arrington secured support from respected Black leaders in the city for a run for mayor, and also endeavored to secure support from white business leaders should he make it to a runoff. As a candidate, Arrington promised to shut down "whiskey, dope and gaming houses" and upgrade street lighting as part of a larger effort to crack down on criminal activity. He promised to tighten the city budget and improve fiscal policies. He also pledged to bring in a diverse staff and to hold frequent meetings with community and business leaders to generate productive ideas for civic improvement. He also pledge to encourage small business, establish a tenant-landlord code that would provide incentives to improve rental housing, and to upgrade the role of community resource officers to reach out to neighborhoods.

Arrington was by far the biggest vote-getter in the 1979 primary and went on to eke out victory against conservative candidate Frank Parsons in the runoff. In his inaugural address, Arrington told the story of his parents moving to Birmingham for an opportunity, and how that story is really everybody's story in Birmingham. He acknowledged the historic importance of the occasion, but insisted that he entered office humbly and pledged to give his very best to the office of mayor.

During his second term, Arrington aggressively pursued an annexation strategy first proposed under Vann's leadership. Birmingham acquired a 7,000-acre parcel northeast of downtown where it developed the Birmingham Turf Club and also used the "long lasso" doctrine to pick up other city-owned areas in Birmingport, Oxmoor Valley and along the U.S. Highway 280 corridor.

In a 1985 interview, Arrington said he had not decided whether to run for a third term. He noted that offers to return to academia were beginning to dry up. He bought a 40% stake in James Parker's Chapel Funeral Service, and formed a consulting company to cultivate clients for Time Energy Systems of Houston, Texas. He was quoted as saying, "If I serve another term, I don't want to be caught in a situation where I don't have any viable alternatives except to stay in the mayor's office, because I don't think I'd like to do it again (for a fourth term)."

Arrington was re-elected to his fourth term in the 1991 Birmingham mayoral election, winning 63 percent of the overall vote, including 95 percent of African American votes and just under 15 percent of white votes. The election was held under the shadow of an investigation by U.S. Attorney Frank Donaldson into an alleged kickback scheme with Atlanta architect Tarlee Brown. The mayor was charged with contempt when he failed to hand over documents about political appointees made from his office. Arrington argued that the investigation was part of a pattern of harassment of African American elected officials by the FBI. Donaldson and his aides countersued, claiming that Arrington's public statements slandered his office.

| Preceded by: David Vann |

Mayor of Birmingham 1979–1999 |

Succeeded by: William Bell (interim) |

Personal life

Arrington and his wife, the former Rachel Reynolds, had eight children.

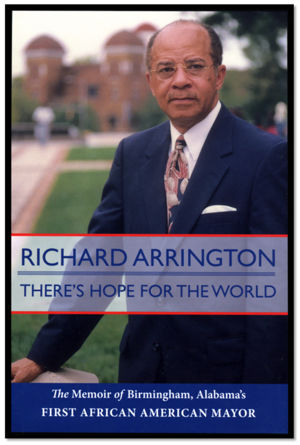

In his retirement, Arrington moved to the suburb of Hoover and kept a relatively quiet profile. In 1999 he was named the founding director of Alabama State University's "Center for Leadership and Public Policy". He described the $72,000 per year position as a consulting job, which he performed from home. In 2008 he completed a memoir of his years in office entitled There's Hope for the World.

In 2009 Arrington began to re-engage with Birmingham politics. He moved his voting registration from his Hoover home to the home he still kept in Vinesville. In March he and Earl Hilliard formed a "New Jefferson County Citizens Coalition" to support candidates for the 2009 Birmingham City Council election. The failure of his slate to generate voter support and the presence of other strong candidates convinced Arrington not to throw his hat in the ring for the 2009 Birmingham mayoral election.

As a trustee he helped to create the University's "Center for Leadership and Public Policy", which hired Richard Arrington as its first interim director.

Arrington was inducted into the Alabama Academy of Honor in 2015 and was presented with the Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in 2017.

In 2018 Arrington cooperated with federal prosecutors who charged former city attorney Donald Watkins with fraud and conspiracy. He testified that Watkins had asked him to circumvent banking regulations by taking out personal loans from Alamerica Bank and then loaning that money to Watkins. That same year he was appointed to the Jefferson County Community Service Committee, and subsequently elected as chair.

Publications

- Arrington, Richard (2008) There's Hope for the World: The Memoir of Birmingham, Alabama's First African-American Mayor Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press

References

- Friedman, Richard (October 19, 1979) "'Organization' brought Arrington commanding lead" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Frieden, Kitty (November 18, 1979) "Here's a list of promises Arrington hopes to keep" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Franklin, Jimmie Lewis (1989) "Back to Birmingham: Richard Arrington Jr, and His Times" Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press

- Kelly, Mark (October 20-November 10, 2005) "Toward a New Birmingham: A Four Part Series on the Life and Times of Richard Arrington, Jr." Birmingham Weekly.

- Bass, Jack. (July 18, 1974) "Oral History Interview with Richard Arrington." Southern Oral History Program, Series A: Southern Politics. Manuscripts Department. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. - accessed September 6, 2007

- White, Dave (July 28, 1985) "Arrington: He's wondering what he'll do when political game is over" The Birmingham News, p. 2A - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Smothers, Ronald (January 20, 1992) "Charge Against Mayor Strikes Chord in Birmingham." The New York Times

- "With 700 Supporters Rallying Round, Birmingham Mayor Goes to Prison." (January 24, 1992) Associated Press/The New York Times

- "Birmingham Mayor Richard Arrington Wins Fifth Term as Chief Exec." (November 6, 1995) Jet, Vol. 88, No. 6, pp. 4–5

- Owen, Sallie (August 26, 1999) "Richard Arrington will head Alabama State University's Center for Leadership and Public Policy." Montgomery Advertiser

- Bryant, Joseph D. (October 11, 2008) "Arrington recalls tenure as Birmingham mayor in new memoir." The Birmingham News

- "Arrington aiming for mayor?" (March 26, 2009) The Birmingham Times

- Whitmire, Kyle (March 16, 2019) "An Alabama fraud story: The many faces of Donald Watkins." The Birmingham News