Hazel Farris

Hazel Farris (born c. 1880; died December 20, 1906 in Bessemer) was a rumored murderer, a possible suicide, and, after her death, a celebrated "mummy". As Hazel the Mummy, her desiccated remains were displayed in traveling carnivals and, later, at the Bessemer Hall of History. She was cremated shortly after a 2002 appearance on "The Mummy Road Show" on the National Geographic Channel.

Legend

University of Alabama folklorist Elaine Katz pieced together a comprehensive composite narrative from various accounts of Farris' life and death:

Hazel, an orphan, became a young beautiful housewife, in Louisville, Kentucky. She and her husband argued over her habit of spending too much money. Over breakfast on August 6, 1905 she announced her intention to purchase a new hat, provoking her husband to blows. During the ensuing struggle she got hold of a pistol and fatally shot her husband. As it happened, three police officers were in the vicinity, walking back to their station. They ran to the house, finding her holding the gun over her husbands body. She turned and killed all three. A crowd gathered and a deputy Sheriff attempted to take her by surprise. He succeeded only in shooting off Hazel's ring finger before she returned a deadly shot. She fled down an alley, eluding pursuers, and, despite a $500 reward, managed to get as far as Bessemer, where she settled to begin a new life.

Accounts differ as to whether she passed herself off as a schoolmarm and drank on the sly, or whether she was more open in her wantonness, working as a madam. In either case, she continued using her married name in her adopted home, a rough town with a reputation for vice and violence. She confided in a suitor, possibly a police officer, who sold her out. As police advanced on December 20, 1906 she locked herself in her room. Rather than submit to arrest and trial, she drank a fatal cocktail of alcohol and poison.

Hazel's body was taken to a nearby furniture store, possibly Adams Vermillion Furniture, which sold coffins and functioned as an informal funeral parlor. Though most accounts refer to her as an orphan, one informant claimed that her father, partner in a 3rd Avenue furniture store, had taken Hazel's corpse and immediately notified her parents in Kentucky. The mother wrote back, asking that he not bury her as she would come to claim the body. She never did appear, due, it seems, to her father's not wanting anything to do with the matter and her lack of funds.

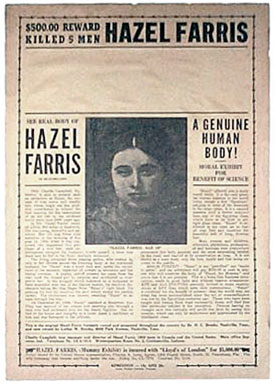

To her caretakers' surprise, Hazel's body did not decay in the usual manner. Instead the body dried to a taut-skinned skeletal 37-pound mummy. Because of her notoriety and the novelty of her preservation, the furniture dealer struck upon the idea of recouping his expenses by charging the curious a dime to see her, propped against a wall in the back of the store. He then sent the body by boxcar to his brother in Tuscaloosa, who exhibited her the same way in his store. A Captain Harvey Lee Boswell also exhibited the "mummy" before traveling showman Orlando Clayton Brooks purchased the body for $25 and added her to his touring menagerie in 1907. Brooks continued to exhibit the mummy for 40 years, carting her around on the running board of his Oldsmobile. He offered a $500 reward to anyone who could demonstrate that the body was not a genuine natural marvel. When rumors spread that rubbing the mummy's hand brought good luck, Brooks offered the opportunity to his patrons at an extra 25¢ charge. Shortly after World War II, Brooks and Hazel even toured Europe, where she was displayed before royal audiences.

The post-war economy did not favor traveling carnival exhibits and Brooks retired to Coushatta, Louisiana where he died in 1950. A disputed account has it that, in his will, Brooks left Hazel's mummy to his then 12-year-old great nephew, under certain conditions revealing a certain feeling of guilt for his crassly commercial treatment of her bodily remains. A note in Hazel's makeshift casket is supposed to have read: "This is Hazel. Take care of her because I haven't. I've shown her as a freak, and I realize now that is not what she is. She must be one of a kind, and she is yours. Never sell her or show her as a freak, and never bury her. I must pay for my crime and so must Hazel. If you ever show her, you must donate all the money to charity, for I did not."

The nephew, who lived in Nashville, Tennessee, did indeed place her on exhibit, offering his own lengthy recounting of Mrs. Farris' history and the miraculous preservation of her remains. As an educational curiosity, Hazel raised funds for schools and churches, mainly in Tennessee. She also became a regular attraction at the Bessemer Hall of History, helping get the museum off the ground. Her final appearance in Bessemer took place in October 1994.

In later years, the corpse passed to the next generation, who were less enamored of the ghastly presence in their home and did not feel bound by their ancestor's wishes. In 2002 she was taken to the Pettus, Owen and Wood Funeral Home for cremation. Before the destruction of the mummy, she appeared on television as the focus of an episode of the National Geographic Channel series "The Mummy Road Show".

No primary documents or accounts were found by the show's producers to authenticate the story of Hazel's murderous exploits. An autopsy performed for the show indicated that, though the body was infused with traces of arsenic, Hazel likely died from pneumonia rather than from ingesting poison. It was surmised that the substance was used in a makeshift attempt at preservation using materials at hand. Arsenic may have been available in the Bessemer area due to its use in mining. The corpse was missing two fingers; one that appeared to have been shot off about a year before death, and the other detached post-mortem. The producers of the program concluded that it was more likely that Hazel's story was invented after the fact to explain the condition of the remains.

See also

References

- Katz, Elaine S. (Winter 1978) "Variation as Relative Perception in the Legend of Hazel Farris". Mid-South Folklore Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 55-64

- Abrams, Vivi. (November 1, 2004) "Bessemer mummy legend endures." The Birmingham News

- "National Geographic probes story of Ada mummy." Claremore Daily Progress

- Quigley, Christine. (1998) Modern Mummies: The Preservation of the Human Body in the Twentieth Century. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786404922

- Conlogue, Jeremy and Ron Beckett. (September 2005) Mummy Dearest: How Two Guys in a Potato Chip Truck Changed the Way the Living See the Dead ISBN 1592285449

External links

- "http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jAQeHCghK0 An Unwanted Mummy" (April 1, 2002) Episode 12 of The Mummy Road Show. National Geographic Channel

- A brief remembrance at Livejournal.com