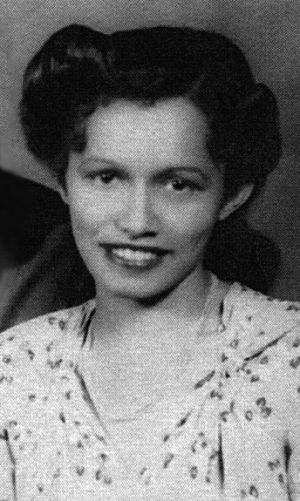

Esther Cooper Jackson

Esther Victoria Cooper Jackson (born August 21, 1917 in Arlington, Virginia; died August 23, 2022 in Boston, Massachusetts) was a civil rights activist, social worker, magazine editor and executive secretary of the Southern Negro Youth Congress.

Esther was the daughter of George Posia Cooper and Esther Georgia Irving Cooper, who served as president of the Arlington branch of the NAACP. She attended segregated schools as a child, graduating from Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Washington D.C. She earned her bachelor's degree at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio in 1938 and went on to complete a master's degree in sociology from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee in 1940, with a thesis entitled "The Negro Woman Domestic Worker in Relation to Trade Unionism".

That research had been inspired by her observation of domestic workers in the dormitories at Oberlin and her experiences performing domestic labor for other domestic workers at a settlement house in Nashville. She attempted to present her research to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) to interest them in a campaign to organize domestic workers under the provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act and National Labor Relations Act, but found little traction. After graduating she accepted a Rosenwald Fellowship researching the attitudes of young Black Americans toward World War II.

Esther had planned to parlay her fellowship research for a doctoral program at the University of Chicago, but during a summer she joined a colleague from Fisk, James E. Jackson at a voting project led by the Southern Negro Youth Conference in Birmingham. They married in 1941 and turned from academic pursuits to full-time activism.

The couple remained in Birmingham, working with Louis and Dorothy Burnham, Ed Strong, Frank and Sallye Davis and others to promote the organization by organizing local councils, and in a larger sense, to empower Black and White workers. Though the group had no formal ties to the Communist Party, many of them, including James Jackson, had been inspired by socialist political movements. As she put it, "Marxism taught my husband to seek the answer here in an alliance of the Negro people with white workers for immediate social gains and the eventual establishment of a social system in which economic exploitation and Jim Crow oppression would be profitable to no one and would cease to exist."

Her Rosenweld project was the basis for a SNYC delegation to Washington D.C. in May 1942 where she participated in meetings with Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, Attorney General Francis Biddle and others to advise on efforts to enlist Southern Black youth into the war effort. James Jackson himself joined the U.S. Army in 1943 and served for 18 months in the Pacific.

Locally, SNYC also worked on efforts to eliminate poll taxes and lobbied the Birmingham Park and Recreation Board to reopen the swimming pool at Tuxedo Park. In January 1946 they organized marches for Black veterans denied voter registration. Esther Jackson served as a delegate to the 1945 World Youth Congress in London, and chaired the American Subcommittee on Problems of Dependent Peoples. Esther was elected chief executive officer of SNYC. In October 1946 her husband resigned from SNYC to accept an appointment as state chair of the Communist Party of Louisiana. He was arrested in November for praising the Russian revolution, but the charges were dismissed. In 1947 the Jacksons moved to Detroit, Michigan to support organizing efforts at the Ford Motor Company. In 1949 Jack was appointed Southern Regional Director for the Communist Party.

Meanwhile, most of the Birmingham group had relocated to Brooklyn, New York by the 1950. James was one of a group of Communist Party officials indicted under the Alien Registration Act in June 1951. He became a fugitive to avoid prosecution. Esther relocated to Brooklyn to rejoin their network of friends there. The FBI kept her and her two young daughters Harriet and Kathryn under constant surveillance. She wrote a pamphlet about the family's persecution which was published by their newly-organized National Committee to Defend Negro Leadership in 1953. The same group also launched the monthly newspaper, Freedom, which featured a column by Paul Robeson. In the late 1950s, she worked as a social worker for the Girls Scouts of America and as an educational director for the New York State Urban League.

After Louis Burnham's death in 1960, Esther and James Jackson worked with W. E. B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois, John Oliver Killens, Jack O'Dell, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Lorraine Hansberry and others to bring to life his goal of launching a quarterly literary journal, which was entitled Freedomways. Jackson served as managing editor of the periodical through its entire run to 1985. The quarterly had a global influence and has been deemed a key precursor to the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. She was honored by the National Alliance of Third World Journalists in 1984 and presented with a lifetime achievement award by the New York Association of Black Journalists in 1989.

James Jackson died in 2007. Esther lived in a retirement community in Boston until her death, which came two days after her 105th birthday in 2022. The couple's papers are archived as part of the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University. Her personal library was transferred to the Charles Evans Inniss Memorial Library at Medgar Evers College / City University of New York, where it has been made accessible as "The Esther Cooper Jackson Book Collection".

Publications

- Jackson, Esther Cooper (1953) This Is My Husband: Fighter for His People, Political Refugee. National Committee to Defend Negro Leadership. National Museum of African American History and Culture. Smithsonian Institution.

- Jackson, Esther Cooper, ed. w/ Constance Pohl (2001) Freedomways Reader: Prophets in Their Own Country. Basic Books ISBN 9780813364520

References

- Adams, Oscar W. (March 10, 1946) "What Negroes Are Doing." The Birmingham News, p. 8B

- Kelley, Robin D. G. (1990) Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press ISBN 9780807842881

- Brown, Sarah Hart (2003) "Esther Cooper Jackson: A Life in the Whirlwind." in Bruce E. Clayton & John A. Salmond, eds. "Lives Full of Struggle and Triumph": Southern Women, Their Institutions, and Their Communities. University Press of Florida ISBN 081302675X, pp. 203–224

- Bond, Jean Carey (2006) "Roots of the Fight for Rights: Esther Jackson and Freedomways magazine." remarks at James and Esther Jackson , The American Left, and the Origins of the Modern Civil Rights Movement symposium at New York University. Republished as "Freedomways Magazine and the Roots of the Fight for Rights" (November 1, 2006) Black Agenda Report

- McDuffie, Erik S. (2008) "Esther V. Cooper's 'The Negro Woman Domestic Worker in Relation to Trade Unionism': Black Left Feminism and the Popular Front." American Communist History. Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 203–209

- Lewis, David Levering; Michael H. Nash & Daniel J. Leab, eds (2010) Red Activists and Black Freedom: James and Esther Jackson and the Long Civil Rights Revolution. Routledge ISBN 9781317990604

- Haviland, Sara Rzeszutek (2015) James and Esther Cooper Jackson: Love and Courage in the Black Freedom Movement. University Press of Kentucky ISBN 9780813166261

- Willis, Samantha (November 22, 2016) "Q&A: Esther Cooper Jackson." Richmond magazine

- Roberts, Sam (September 1, 2022) "Esther Cooper Jackson, 105, Dies; Pioneer of Civil Rights Movement." obituary. The New York Times, p. B11

External links

- James E. Jackson and Esther Cooper Jackson Papers at library.nyu.edu

- Esther Cooper Jackson Book Collection at cuny.edu