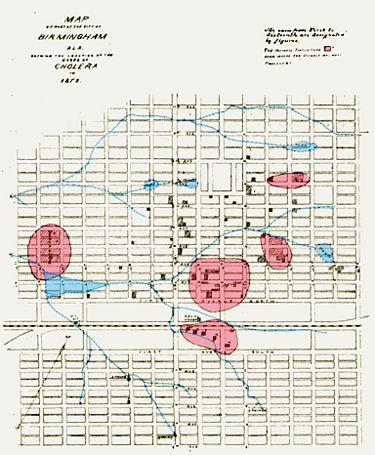

1873 cholera epidemic

The Cholera Epidemic of 1873 afflicted several cities in the Southeastern United States. This outbreak began in Memphis and moved along rail lines to Nashville, Huntsville, Birmingham, and Montgomery. Birmingham was particularly hard hit by the illness due to the lack of urban infrastructure and the poor housing conditions of many citizens. At least 128 people died from cholera, while half of Birmingham’s 4,000 residents fled the city.

The disease was first introduced to Birmingham from Huntsville. The first patient, who had been in the city for weeks, became ill on June 12, three days after taking receipt of his bedding, shipped to him from Huntsville, where it had been used in a disease-stricken area. He died within 24 hours of taking sick. The attending physicians did not at first diagnose cholera, and no care was taken to disinfect his bedclothes, which were discarded behind the house. The next cases, two young sisters of the Hughes family, whose members had visited the house of the first patient, also died quickly, with their effects also discarded carelessly into a marshy branch behind their house which fed into a basin on the edge of the "Baconsides" quarter of shanties.

Baconsides became the primary incubator for the disease in Birmingham as its refuse flowed into the same basin in which infected clothing and bedding were washed, and from which water was taken up in barrels for use around the city. Frequent rain showers and summer heat contributed to the climate in which the disease rapidly spread across the city.

After a community-wide Fourth of July celebration in Blount Springs, the outbreak became general. While the African American community would remain the hardest hit, the illness moved rapidly through the rest of Birmingham. City leaders ordered that the town bell, which had rung for deaths, no longer be used as its tolling was too frequent and too distressing. Many residents left the city at this point fearing for their health. Fortunately, the epidemic became milder over time and did not spread to Mobile or New Orleans.

There are numerous stories of personal courage during this period. Many medical professionals stayed to tend to the sick despite the risk to their own health. Other residents contributed by sharing their private wells and rain cisterns with the community. One of the most popular local tales involves Louise Wooster, a local prostitute, who, along with her associates assisted in caring for the sick during this period. Some of these individuals wrote down accounts of their experiences during this trying time. Birmingham’s Oak Hill Cemetery contains the gravesites of many of the victims of the cholera epidemic, along with those who cared for them.

References

- Caldwell, H. M. (1892) History of the Elyton Land Company and Birmingham Alabama. Birmingham: Birmingham Printing Company

- Jordan, M. H. (1875) Cholera at Birmingham Alabama in 1873. The Narrative of the 1873 Cholera Epidemic] Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office

- Luckie, Mrs. (n. d.) Sketch of the 1873 Cholera Epidemic. On reserve in the Birmingham Public Library Archives in the Ferguson Collection.

- Means, T. A. (1875) Report of a Case of Epidemic Cholera Which Occurred at Montgomery, Alabama in 1873. The Narrative of the 1873 Cholera Epidemic. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office

- Wooster, L. C. (1911) Autobiography of a Magadalen. Birmingham: Birmingham Printing Company.

- Sulzby, James F. (1945) Birmingham Sketches from 1872 through 1921. Birmingham: Oxmoor Press

- Rosenberg, Charles. (1962) The Cholera Years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Norton, Bertha Bendall (1970) Birmingham's First Magic Century: Were You There?. Birmingham: self-published/Lakeshore Press

External Links

- Birmingham Cholera Epidemic of 1873. (August, 1874) Report and map by Mortimer Jordan, Jr.