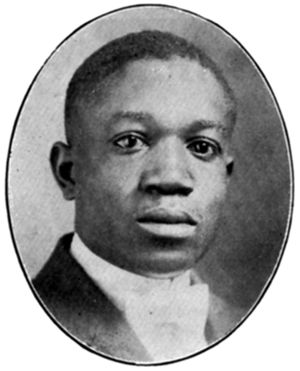

A. G. Gaston

Arthur George Gaston (born July 4, 1892 in Demopolis (Marengo County) – died January 19, 1996 in Birmingham) was an African-American entrepreneur who established a number of businesses in Birmingham, catering primarily to black customers under the city's ingrained segregation. Though not a vocal supporter of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, he did provide support to the movement and played a significant role in the struggle to integrate Birmingham in the 1950s and 60s.

Early life

Gaston was born to Tom and Rosa McDonald Gaston in Demopolis, but grew up in the home of his grandparents, Joe and Idella Gaston. He moved to Birmingham as a boy in 1905 when his mother, the cook for the Loveman family, was brought to the city.

Gaston served in the army in France in World War I, then went to work in the mines run by Tennessee Coal & Iron Co. in Fairfield. He hit on the plan of selling lunches to his fellow miners, then branched into loaning money to them at twenty-five percent interest. While still working at the mine he began offering burial insurance to co-workers and to the community at large though the Booker T. Washington Burial Society. In the 1920s, as part of a deal for the hand of his wife, Creola, he partnered with his father-in-law Dad Smith to establish the mortuary firm of Smith & Gaston Funeral Home.

Business

Driven out of Fairfield because of Smith's political differences with the mayor, he bought property on the edge of Kelly Ingram Park in downtown Birmingham, where he moved the Smith & Gaston business, in 1938. Gaston extended his business holdings throughout the neighborhood and beyond, opening a savings and loan in the early 1950s, the first black-owned financial institution in Birmingham in more than forty years. Smith & Gaston sponsored gospel music programs on local radio stations and launched a quartet of its own. In 1954 Gaston built the A. G. Gaston Motel on the site adjoining Kelly Ingram park where the mortuary had once stood.

Civil Rights Movement

While his father-in-law had been an active supporter of voting rights and his second wife was a founder of the National Council of Negro Women, Gaston himself had kept a low political profile through most of the 1940s and 1950s. He offered financial support to Autherine Lucy, who had sued to integrate the University of Alabama, and had provided financial assistance to residents of Tuskegee who faced foreclosure because of their role in a boycott of white-owned businesses to protest their disenfrachisement. When Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth founded the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights in the wake of the outlawing of the NAACP in the State of Alabama in 1956, the group held its first meeting at Smith & Gaston's offices.

Gaston was far more reluctant to confront white authorities and the white business establishment directly. When students at Miles College, a historically black college in Fairfield, attempted to use sit-ins and boycotts to desegregate downtown Birmingham in 1962, Gaston used his position as a member of the board of trustees of the institution to dissuade them from continuing their campaign while he pursued negotiations with them. Those negotiations produced some token changes, but no significant progress toward desegregating the stores or hiring black employees.

When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, represented locally by Rev. Shuttlesworth, proposed to support those students' demands in 1963 by widespread demonstrations, challenging both Birmingham's segregation laws and Local Police Commissioner Bull Connor's authority, Gaston opposed the plan and tried to deflect the campaign from public confrontation into negotiations with white business leaders. Gaston tried to talk Martin Luther King Jr out of going through with the planned Easter boycott of downtown business and may have bailed him out of jail against his wishes in April 1963.

At the same time, Gaston provided King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy with rooms at his motel at a discount and free meeting rooms at his offices nearby throughout the campaign. He maintained a public show of support for the campaign and not only took part in the meetings with local business leaders. but insisted that Shuttlesworth be brought in since "he's the man with the marbles".

That unity nearly dissolved, however, after Abernathy made some comments about unidentified "Uncle Tom's" and Dr King made it clear that he would press forward with his plans for confrontation. Gaston issued a press release in response in which he obliquely criticized King by lamenting the lack of communication between white business leaders and "local colored leadership".

That press release exposed a significant rift between the activists in the movement. Shuttlesworth described Gaston as a "super Uncle Tom" to the press while complaining that he overcharged for his motel rooms. The leaders of the movement were eager, however, to avoid any public airing of those differences; Shuttlesworth soon apologized, SCLC leaders treated the press release as an expression of support for their campaign while Dr King announced creation of a special committee of local leaders, including Gaston, to meet every morning to approve each day's plans.

That committee had no real power, however, as became clear when the movement encouraged school children to march against segregation on May 2, 1963. Gaston protested the strategy, telling King "Let those kids stay in school. They don't know nothing." King replied, "Brother Gaston, let those people go into the streets where they'll learn something." The demonstrations continued.

Unknown persons attempted to blow up the part of the Gaston Motel where King and Abernathy were staying on May 12, 1963. Later that day Alabama State Police dispatched to clear Kelly Ingram Park invaded the motel, clubbing those who could not escape. Unidentified persons later threw firebombs at Gaston's house, a day after he and his wife had attended a state dinner at the White House with President Kennedy.

Gaston remained disaffected from Dr King, urging him to stay away, in a statement released in September, 1963, after Dr King announced plans to return to Birmingham to resume demonstrations. As it turns out, Dr King did not revive the campaign.

Radio

In 1976 Gaston was approached by WENN general manager Joe Lackey about a loan that would allow the station's mostly black staff to join with him to purchase it from its out-of-town owners. Instead, Gaston bought the station himself, triggering a walkout by the on-air staff. Gaston's BTW Broadcasting Service recovered and became a leading voice in the black community.

Kidnaping

Just after midnight on the morning of January 24, 1976 Gaston and his wife were assaulted and Gaston was abducted from his home, handcuffed and forced into the back of his own 1972 Cadillac El Dorado under a pile of blankets. Minnie, also cuffed and suffering a dislocated shoulder, regained consciousness and alerted the funeral home, which in turn contacted police. The car was located soon later with Gaston inside. The driver, Charles Lewis Clayborn, Jr was taken into custody and later convicted and sentenced to life in prison. The Gastons were treated at Baptist Medical Center Montclair. Minnie, in particular, remained haunted by the brutal attack and arranged for guards to patrol the couple's home for a while afterward.

Retirement

In his later years Gaston began turning over more of his business to subordinates and he and his wife spent more time away from Birmingham at their condominium in Fort Myers, Florida.

Gaston died in 1996 at age 103. He left behind three companies, the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, A. G. Gaston Construction, and CFS Bancshares. The City of Birmingham owns the motel, which it plans to make into an annex to the Civil Rights Institute, which was built on the site of the old insurance building. His net worth was estimated to be more than $130,000,000 at the time of his death.

Birmingham City Schools' A. G. Gaston School in Roosevelt City is named for Gaston.

References

- Gaston, A. G. (1968) Green Power: The Successful Way of A. G. Gaston. Troy:A. G. Gaston Boy's Club/Troy University Press

- Carol, Jenkins; Elizabeth Gardner Hines (December 2003). Black Titan, A.G. Gaston and the Making of a Black American Millionaire. New York: One World/Ballantine ISBN 0345453476

- Branch, Taylor (1988). Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954 -1963. New York: Simon & Schuster ISBN 0671687425

- "A. G. Gaston" (November 28, 2009) Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia - accessed January 21, 2010