Bull Connor

- This article is about the former Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety. For the newspaper byline psuedonym, see B. U. L. Conner.

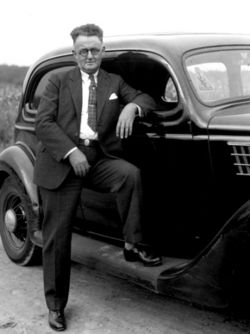

Theophilus Eugene L. "Bull" Connor (born July 11, 1897 in Selma, Dallas County; died March 10, 1973 in Birmingham) was Commissioner of Public Safety for the City of Birmingham from 1937 to 1952 and from 1956 to 1962. He was, throughout his career, one of the most visible and feared enforcers of segregation ordinances, and became an international villain during the Civil Rights Movement. Locally, he was perceived more as a comic figure, and sometimes as an embarrassment, by the almost entirely white electorate.

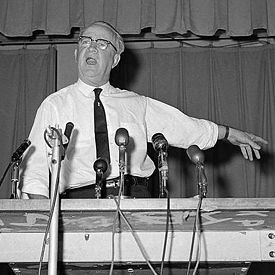

During the 1960s, Connor became a symbol of the fight against integration for using fire hoses and police attack dogs against unarmed, non-violent protest marchers. The spectacle of this being broadcast on national television served as one of the catalysts for major social and legal change in the South and helped in large measure to assure the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; thus, Connor's brutal tactics helped to bring about the very change that he was opposing.

Early life and career

Connor was the son of King and Molly Godwin Connor of Selma.

Connor and his wife, the former Beara Levens, settled in Birmingham in 1922 and had a daughter. Connor worked as a telegraph operator. As a sideline he forwarded baseball reports from the telegraph office to local pool halls, using a megaphone. His "bull horn" and the recognizable egotism of Birmingham Post columnist Dr B. U. L. Conner ran together to give "Old Bull" the nickname that he identified himself with for the rest of his life.

Connor's experience reporting on baseball games led to his hiring as radio announcer for the Birmingham Barons, where he gained much name recognition and popularity. He was known for his ability to stretch the word "out" into two or more syllables.

Connor leveraged that popularity for his first foray into politics. Though he claimed to have entered the race on a lark, he won the Democratic primary for a seat on the Alabama House of Representatives in 1934. As a legislator he supported mainly populist measures. Though he bitterly opposed proposals by Governor Bibb Graves for raising the statewide sales tax and increasing licensing fees, he did vote to extend the state's poll tax. He generally supported a pro-union agenda and voted against an anti-sedition bill meant to stifle union activity. When a controversial bill was entered by William McDermott of Mobile to replace the goldenrod as state flower with the azalea, he suggested a compromise, offering an amendment to name the azalea as Alabama's "assistant state flower".

Connor did not stand for a second term in 1936, instead running to head Birmingham's Department of Public Safety on the scandal-plagued Birmingham City Commission in the 1937 Birmingham municipal election.

Commissioner of Public Safety

In all, Connor served as Commissioner for 23 years between 1937 to 1963 (interrupted by scandal in the early 1950s). He emerged into wider public awareness when he ordered attendees of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare at Municipal Auditorium in 1938 not to "segregate together". First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt defied his order by pulling her chair into the middle of the aisle separating black and white delegates.

On October 1940 Connor defied a court order by padlocking the Galax Theater after a showing of the 1936 film "Club de femmes" (retitled "French Girls Club"). In January 1941 he, along with two city attorneys and police chief T. A. Riley were held in contempt and ordered to spend 48 hours in jail. Upon his release Connor was serenaded by "Happy Days are Here Again" and his office festooned with flowers and a "Welcome Back" banner.

Birmingham Police chief Luther Hollums retired in November 1942 and later blamed Connor for making continued service unbearable. He claimed that "any improvement in the crime situation atained [sic] during the last few years of my service in the department was NOT because of Mr. Connor but, IN SPITE OF Mr. Connor." Hollums went on to cite Connor's habit of swearing loudly in the presence of ladies, along with his interference in the department's work, as, "the LEADING cause of my retiring after 25 years of service, notwithstanding the fact that my health is good and I am still working every day."

Despite the publicity of having Hollums' letter made public, Connor survived electoral challengers Osa Andrews, Chester Mullins, Marion Hogan and John Rogers in the 1945 Birmingham municipal election.

In May 1948 Connor's officers arrested a U.S. Senator from Idaho, Glen H. Taylor, who was running for Vice President of the United States on the Progressive Party ticket with Henry Wallace. Taylor, who had attempted to speak to the Southern Negro Youth Congress, was arrested for violating Birmingham's segregation laws.

Connor's concerted effort to enforce the law was sparked by the group's reported Communist philosophy, with Connor noting at the time, "There's not enough room in town for Bull and the Commies." On July 18, 1950 the Commission passed an ordinance proposed by Connor that made "communication or voluntarily association" with the Communist Party a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of $100 and 180 days in jail. Connor gave any communists 48 hours to vacate the city.

Political activities

Connor led the Alabama delegation in a walkout of the 1948 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia after the party adopted a plank in its platform affirming the rights of African American citizens to vote, to work, to serve in the armed forces, and to be secure in their persons. As City Commissioner he hosted the hastily-organized 1948 States Rights Democratic Party convention at Municipal Auditorium at which South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond was nominated for president.

In 1950, Connor campaigned for Governor of Alabama on a platform of "protecting employment practices, law enforcement, segregation and other problems that have been historically classified as states' rights by the Democratic party." That bid, along with another attempt in 1954, failed.

Loss of office

In late 1951, Connor became embroiled in a feud with city detective Henry Darnell after Connor's wife claimed to have witnessed an incident of police brutality. Connor investigated and charged Darnell with conduct unbecoming an officer.

On December 26 of that year Connor himself was arrested after having being found in a hotel room with his 34-year-old secretary, Christina Brown a few days after a Christmas party. Connor claimed he had been set up and blamed internal dissension in the Birmingham Police Department. He was convicted in the city's police court, fined $100, and given a 180-day sentence. Attorney T. C. McVea, representing an anonymous group of dissatisfied civil service workers, circulated a recall petition shortly after his conviction. Impeachment proceedings followed, but those efforts hit a dead end when the Alabama Court of Appeals threw out Connor's conviction on June 11, 1952. Connor did not run for the city commissioner position in the subsequent election.

Return to the Commission

After returning to office in 1956, Connor quickly resumed his heavy-handed approach to dealing with perceived threats. One prominent instance came when a meeting at Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth's house with three Montgomery, Alabama ministers was raided. Connor feared that a spread of the bus boycott that had succeeded in Montgomery was imminent. The ministers were arrested for vagrancy. A federal investigation into the arrests followed, but Connor refused to cooperate. Connor ordered the purchase of two armored riot cars, used to intimidate demonstrators and loiterers.

Shuttlesworth had faced continuous dangers in the previous two years, having seen his church bombed twice. He, his wife and a white minister were also attacked by a mob after attempting to use white restrooms at the local bus station.

In 1960, Connor was elected Democratic National Committeeman for Alabama, soon after filing a lawsuit against the New York Times for $1.5 million, for what he said was insinuating that he had promoted racial hatred. Later dropping the amount to $400,000, the case would drag on for six years until Connor lost a $40,000 judgement on appeal.

Connor easily won re-election in 1961 with 61% of the vote in the May 2 Democratic primary and no opposition in the October general election. In March 1962 he kicked off a campaign for Governor of Alabama with a rally at the Temple Theater. He garnered 23,019 votes (3.6%) in the June 3 primary, which was won by George Wallace.

In November 1962, Birmingham voters changed the city's form of government, with the mayor working alongside a separate City Council instead of with two fellow city commissioners. The move had been in response to the extremely negative perception of the city (which had been derisively nicknamed "Bombingham") among outsiders. The most prominent example of this continuing embarrassment came in 1961 when Sidney Smyer, president of the city's Chamber of Commerce was visiting Japan, only to see a newspaper photo of a Birmingham-bound bus engulfed in flames near Anniston.

Connor attempted to run for mayor, but lost on April 2, 1963. He and his fellow commissioners then filed suit to block the change in power, but on May 23, the Alabama Supreme Court voted against the lawsuit, ending a 23-year tenure in the post for Connor.

Project Confrontation

The day after the April election, civil rights leaders, led by Dr Martin Luther King Jr, began "Project Confrontation" in Birmingham, actively provoking Connor and his subordinates (and, by extension, other Southern police officials). King's arrest during this period provided him the opportunity to compose his legendary "Letter from Birmingham Jail" The goal of this movement was to cause mass arrests and subsequent inability of the judicial and penal systems to deal with this volume of activity. One key strategy was the use of children to further the cause, a tactic that was criticized on both sides of the issue. The short-term effect only increased the level of violence used by Connor's officers, but in the long term the project proved successful in stimulating the nation's conscience.

Birmingham Post-Herald columnist Duard Le Grand summed up the contexts in which Connor's actions were seen:

The difference between the societies of the South and the rest of the nation, far more than the Bull Connors and Gene Talmadges and the Tom Heflins, kept the regions eyeing each other uneasily for so long, and made it possible for Connor, during the 1963 demonstrations, to perform simultaneously a comic role for his local audience and the part of a heavy on the nightly television news shows in the rest of the country.

At the end it was the society which produced him that changed, rather than Connor. With an enlarged electorate and a wide range of federal civil rights laws in force, Birmingham looked elsewhere for the entertainment-cum-leadership which Connor so long provided.

On June 3, 1964, Connor returned to a government post when he was elected to head the Alabama Public Service Commission.

Stroke and later life

Connor suffered a stroke on December 7, 1966 that left him confined to a wheel chair for the rest of his life. He won another term in the 1968 election, but was defeated in 1972, putting an end to his long political career.

He was present in Haleyville's police station on February 16, 1968, when 911 was first used as an emergency telephone number in the United States.

Another stroke on February 26, 1973, weeks before his death, left him unconscious. Survivors included his widow and daughter, and his brother, King Edward Connor. He is buried at Jefferson Memorial Gardens East in Trussville.

References

- "Battle Lines Drawn for Flower Contest" (March 10, 1936) The Tuscaloosa News

- "In Re Willis" (1941) Supreme Court of Alabama. 5 So. 2d 716

- DuBose, Hugh (April 27, 1945) "Bull Connor A Mad Man And A Thorn In Cooper Green's Side, Say Chief Hollums And Mullins." Alabama Radio News, Vol. 5, No. 7

- "Birmingham officials pass anti-red action." (July 19, 1950) The Tuscaloosa News

- "Police Commissioner Connor and a woman found in hotel room" (December 22, 1951) The Birmingham News, p. 1

- "Petition for recall of 'Bull' Connor is signed by hundreds." (January 16, 1952) Florence Times-Daily

- "Eugene 'Bull' Connor Dies at 75", (March 11, 1973) Associated Press

- "Eugene ‘Bull’ Connor Dies at 76; Police Head Fought Integration" (March 12, 1973) The New York Times

- Le Grand, Duard (March 17, 1973) "Eugene Connor was shaped by society in which he lived." Birmingham Post-Herald, reprinted in LaMonte, Ruth Bradbury, ed. (1978) A Singular Presence: Duard Le Grand, Newspaperman. Birmingham: Friends of the Birmingham Public Library

- Nunnelly, William A. (1991) Bull Connor. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press ISBN 0817304959

- "Bull Connor" (March 28, 2006) Wikipedia - accessed March 28, 2006

- Kimerling, Solomon P. & Pamela Sterne King (May 10, 2012–October 2013) "No More Bull: Birmingham's Revolution at the Ballot Box" Weld for Birmingham

External links

- Segregation at All Costs: Bull Connor and the Civil Rights Movement. National History Day documentary