Vestavia (estate)

Vestavia was the 20-acre Roman-inspired estate which served as the home of former Mayor of Birmingham George Ward on the crest of Shades Mountain. The circular home with its surrounding colonnaded portico was built as a replica of a "Temple of Vesta" in 1925. After Ward's death, the landmark was bought from the estate by developer Charles Byrd and opened as a restaurant and tea room to publicize the residential suburban development he dubbed Vestavia Hills. The property was sold again in 1958 to Vestavia Hills Baptist Church which determined, a decade later, that the building should be demolished.

Planning and design

During a 1907 trip to Italy, Ward purchased a souvenir model of what was then called a "Temple of Vesta" (later believed to have been built to honor Ceres, but now known as the Temple of Hercules Victor). The original was a peripteros-style structure constructed in the 2nd century B.C. in the Forum Boarium in Rome. Like that temple, Ward's "Vestavia" consists of a cylindrical building with twenty columns encircling it. The entablature and upper portion of the inner cella of the original had fallen into ruin before the 12th century. In the late middle ages, the ruin was capped with a conical roof bearing directly on the columns and on brick extensions of the broken walls to enclose a church, called Santo Stefano alle Carozze (St Stephen of the Carriages). It was rededicated in the 17th century as Santa Maria del Sole (St Mary of the Sun).

Ward's model would have been a speculative reconstruction of the original Roman temple. Having made the decision, with his client, to use "the rich vari-colored ores of his native mountains" instead of marble, Ward's architect, William Leslie Welton, simplified the decorative scheme of the original. As Ward put it, "I was compelled to drift toward the simplicity of the Doric, and forego the more attractive Ionic columns with their exquisite detail." (quoted in McDavid-1935)

The columns were 32 inches in diameter at the base, and 28 feet tall (proportions more suited to the Corinthian order than the Doric). The stripped-down stucco entablature capping the columns was 60 feet in diameter. It incorporated molded medallions and garlands of flowers and fruits of a style popular for 18th century interiors.

The portico was 14-feet wide from the outer edge to the wall. The masonry walls of the house itself were constructed of uncoursed sandstone, 2 feet thick at the base, with the chimney flue for the massive fireplace concealed inside. The interior on the main floor was an undivided circular space 28-feet across which Ward used as a living room and library. The interior of the walls, with numerous niches for sculpture, were washed to a soft gray color and the windows draped with gold scrims in summer and red velvet in winter. The bookcases placed between windows were hung from the ceiling on stout metal chains.

A circular wrought iron staircase accessed Ward's bedroom suite above, with a small bath and closet concealed behind partitions. Clerestory windows in a raised part of the attic roof provided natural light. Ward decorated the curving wall with postcard reproductions of paintings from the Louvre.

The lower floor was part basement and partly open to the gardens. There was a large semi-circular dining room with room for 42 seats, and a guest suite, along with the kitchen, pantries, servants' quarters and garage.

Ward also built elaborate gardens on the "upper" 10 acres next to the house, including sculpted topiary hedges, statuary, and miniature temple-style houses for three dogs on the property. A large reflecting pool, stocked with goldfish, was contained within low stone walls which hid green and blue subsurface lights. A tiered fountain featured built-in planters for ferns and flowering vines. Near the entrance to the grounds Ward had built a raised dais with a large bronze bowl on a pedestal flanking a throne-like stone chair from which he could survey his domain.

In a sunken garden, accessed by a path lined with hedges and sculpted pedestals bearing portrait statues, including Caesar, Virgil, Sappho, Chronos, Nidia and Glaucus. These alternated with rose-colored garden lights. Numerous metal trellises in the shape of scallop shells supported different breeds of rose. A broad pool was planted with Egyptian lotus. Another well-shaded pool featured a large statue of Vesta poised on a boulder while emptying two large water pitchers. The gardens continued through a "mystic maze" to muscadine arbors, fruit orchards and a field of clover.

The focal point for the gardens was the Sibyl Temple, a domed garden gazebo or "look out" of the monopteros style. The temple and its hillside base were designed by the firm of Miller and Martin, and completed in 1929. The design of the concrete structure, which was originally painted a muted rose color, seems to have several influences. The siting was probably inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli (sometimes associated with the Tiburtine Sibyl). The domed roof may have been inspired by speculative reconstructions of circular temples. The eight fluted columns have capitals resembling those on the Roman "Tower of the Winds" in Athens.

The estate was reached by a driveway paved with crushed white limestone and secured behind a massive wrought iron gate flanked by stone piers topped with planters. The remaining "lower" half of Ward's property below the access road was left in a "rustic" condition, with a few winding pathways.

Landmark status

Vestavia became one of Birmingham's best-known attractions, visible from the Montgomery Highway and depicted on postcards. A fully-illustrated story about the design and construction of the house was published in the Italian magazine La Rivista, edited by Arnaldo Mussolini, brother of dictator Benito Mussolini.

Ward held numerous garden parties there, where servants would dress as Roman soldiers and guests would come wearing togas. Local residents would also drive near the home, and Ward occasionally had public tours of his estate. Harpers magazine editor George Leighton described one such occasion in his 1937 study of Birmingham:

In the afternoon, over beyond Red Mountain which walls in the sprawling city, a local capitalist has opened his grounds to visitors. His mansion, built in imitation of a Roman temple, is cylindrical in shape, made of bits of ore cemented together. By the steps of the mansion stand two black servants in white jackets. One has a felt hat under his arm, the other carries a cap in his hand. Each has pinned to his jacket a green-felt label embroidered in yellow with the Roman standard, the letters SPQR, and his name; Lucullus for one, Caius Cassius for the other. Under a tree is an elaborate sort of Roman throne, tinted green and bronze. Above, swinging from a branch, is a radio concealed in a bird house. Nearby are two dog houses, built like miniature Parthenons, with classic porticoes and tiny pillars. One is labelled Villa Scipio. There is a pool filled with celluloid swans and miniature galleons and schooners. Scattered about are more benches, urns, and painted-plaster sculptures. Among the shrubs and pink-rose hedges trail a procession of men and women, marveling at the splendors, but tired and oppressed by the overpowering heat. Toward sundown the crowd thins out; the Fords and Chevrolets go crossing down the hill.

Lynn Reeves reported later that "Lucullus" was the name given to the cook, "Cataline" to the chauffeur, and "Pompey" and "Marcellus" to the gardeners. Plantings included a bower of cypress, laurel, and chinaberry trees and a pond with Egyptian lotus, lillies, irises and orchids. When Ward was receiving guests, he lit a green-colored beacon. A red light indicated that the gates were closed, and a white light shone during private parties. More strings of lights throughout the gardens formed a "constellation" visible at night from far below. The Alabama Powergram noted that Ward was at one time, "the largest rural electrical customer in the state."

Regular events hosted by Ward included an annual dinner for Latin students from Ramsay High School, a "Blossomtime Festival" with area pageant queens, and numerous piano concerts or listening parties featuring his automatic Victrola VE 10-50 record changer. Notable guests at Vestavia included George Washington Carver, Better Homes and Gardens editor Elmer Peterson, and Arnaldo Mussolini, the brother of the fascist dictator.

Sale

Ward died in 1940. He had intended for the Sibyl Temple to serve as his mausoleum, with a vault constructed into its foundations. However, Jefferson County law prevented him from being buried on the grounds, and he was interred at Elmwood Cemetery instead.

A codicil appended to Ward's will, dated April 13, 1940, stipulated that the house and upper 10 acres would pass to his neices, and lower 10 acres of his estate, including the Sybil temple, would be given to Jefferson County or the city of Birmingham as a public park. Because his debts exceeded his assets, the executors of the estate listed both properties for sale for about $30,000. The estate went unsold for several years, and fell into disrepair. In 1947 it was purchased by developer Charles Byrd who opened a restaurant in the building, which he called the Vestavia Roman Rooms as an attraction for the new residential subdivision of Vestavia Hills.

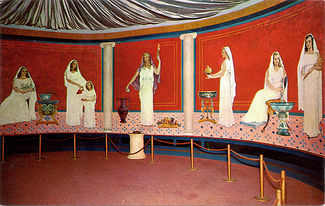

Byrd hired renowned church architect and decorator Viggo F. E. Rambusch to assist local architect Charles Snook with plans for the restoration of the estate in 1948. The upstairs bedroom suite was remade into a recreated "altar room" with new interior murals to match the artwork found in the Roman original. Young socialites posed for the robe-clad figures in the 88-foot by 13-foot work executed by Frances O'Brien. A larger kitchen and banqueting room was added on to the basement. The restaurant served steaks and seafood in the evenings and soups and sandwiches at lunch. Of particular note were Mrs Ewing Steele's orange rolls, which later became a staple at The Club on Red Mountain. Patrons were allowed to bring their own bottles of wine, paying a nominal corkage fee.

A chandelier and benches were removed from the Sibyl Temple in the garden during those renovations. In 1950 Robert Jemison gave Byrd eight marble columns salvaged from the People's Bank, which he used to create a pergola which served as a backdrop for an outdoor stage.

Demolition and relocation of Sibyl Temple

The suburban City of Vestavia Hills was incorporated in 1950, using a drawing of Ward's estate on its official seal. On March 4, 1958 the newly-formed Vestavia Hills Baptist Church purchased the property of the estate and moved its worship services from the Vestavia City Hall to the former banqueting room, raising the old dance floor for the pulpit and installing the choir in the former bandstand. A former hothouse was converted into a baptistry and former storage and utility rooms added by Byrd were enlarged into nurseries. The original rooms of the house and the gatehouse were used for Sunday School classes and office space. Pastor John Wiley observed that his congregation was repeating a pattern established by the early church, which made churches of former pagan temples in the Roman empire.

In a late 1950s brochure, the church acknowledged the need for expansion: "We plan to erect a first building for our educational activities. Later we shall build a new sanctuary. The original structure shall be maintained for its beauty and historical association." An $800,000 fund-raising campaign was started in 1962, with the idea that four new buildings would be put up around the temple. During that campaign, it was estimated that an additional $120,000 would be needed to relocate utilities and repair the 1925 structure. By 1968 the church revised its building plan to include the removal of Ward's former home. The church ran an advertisement in the Wall Street Journal offering the house as, "free for the taking," but received no legitimate offers.

The Women's Civic Club of Birmingham, the Women's Committee of 100 and the Women's Chamber of Commerce joined in opposing the demolition plans and wrote and telephoned area leaders to plea for its preservation. The Alabama Historical Commission backed their efforts in 1969. The protests failed, however, and the the congregation voted to proceed with demolition in 1970. The statuary, kitchenwares and other trappings were sold at public auction which netted $2,971 for the building fund. The event was the public's last opportunity to explore the deteriorating house, which was demolished in April 1971.

The church donated the smaller Sibyl Temple to the Vestavia Hills Garden Club, which moved it to its current location on the mountain at Highway 31. The Temple serves as a symbol for the city of Vestavia Hills, marking the northern entrance into the city, while the main estate building still appears on the city's official seal.

Gallery

References

- McDavid, Mittie Owen (1935) "Vestavia: Classic Home of George Battey Ward" in Historic Homes of Alabama and Their Traditions. Birmingham Branch, National League of American Pen Women, pp. 308-314

- Leighton, George R. (August 1937) "Birmingham, Alabama: The City of Perpetual Promise". Harpers Magazine. No. 1407. pp. 225-242. Republished in Five Cities: The Story of their Youth and Old Age (also published as America's Growing Pains: The Romance, Comedy & Tragedy of Five Great Cities) New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 100-139

- "Vestavia Hills Baptist Church" undated flyer (c. 1960)

- Reeves, Lynn (April 18, 1971) "Passed through many eras. Soon it'll be a memory" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Rewound

- Whiting, Marvin Yeomans (2000) Vestavia Hills, Alabama: A Place Apart Birmingham: Vestavia Hills Historical Society

- Riley, Cindy (Summer 2004). "Vestavia's Sibyl Temple." Alabama Heritage. University of Alabama Press

- "3 civic clubs launch drive to save Vestavia" (November 1968) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Rewound

- Fazio, Michael W. (2010) Landscape of Transformations: Architecture and Birmingham, Alabama. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 9781572336872

- Markham, Madoline (October 1, 2017) "The Legendary Lore of the Vestavia Temple" Vestavia Hills magazine

External links

- Interior photo on Flickr.com