John Henry: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

:''This article is about the folk hero. For the former CFO of the [[Jefferson County Finance Department]], see [[John Henry (CFO)]].'' | |||

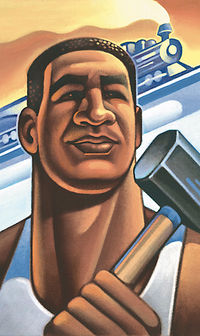

[[File:John Henry stamp.jpg|right|thumb|200px|1996 USPS stamp depicting John Henry]] | |||

'''John Henry''' is an African-American folk hero who has been the subject of numerous songs, stories, plays, and novels. | '''John Henry''' is an African-American folk hero who has been the subject of numerous songs, stories, plays, and novels. | ||

Like other "Big Men" such as Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, and Iron John, John Henry served as a mythical representation of a particular group within the melting pot of the 19th-century working class. In the most popular story of his life, Henry | Like other "Big Men" such as Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, and Iron John, John Henry served as a mythical representation of a particular group within the melting pot of the 19th-century working class. In the most popular story of his life, Henry was born into the world big and strong. He grew to be one of the greatest "steel-drivers" in the railroad-building age. As the story goes, the owner of the railroad bought a steam-powered hammer to do the work of his driving crew. In a bid to save his job and the jobs of his men, John Henry challenged the machine to a contest. John Henry out-muscled the steam hammer, but in the process, he succumbed to exhaustion and died. Older songs refer to him driving blasting holes into rock rather than driving spikes into rail ties. | ||

The truth about John Henry is obscured by time and myth, but one account identifies him as a slave born in [[Alabama]] in the 1840s | The truth about John Henry is obscured by time and myth, but one account identifies him as a slave born in [[Alabama]] in the 1840s who fought his famous battle with the steam hammer along the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in Talcott, West Virginia. A statue and memorial plaque have been placed along a highway south of Talcott as it crosses over the tunnel in which the competition may have taken place. | ||

The railroad historian Roy C. Long found that there were multiple Big Bend Tunnels along the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway. Also, the C&O employed multiple black men who went by the name "John Henry" at the time that those tunnels were being built. Though he could not find any documentary evidence, he believes on the basis of anecdotal evidence that the contest between man and machine did indeed happen at the Talcott, West Virginia site due to the presence of all three (a man named John Henry, a tunnel named Big Bend, and a steam-powered drill) at the same time at that place.< | The railroad historian Roy C. Long found that there were multiple Big Bend Tunnels along the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway. Also, the C&O employed multiple black men who went by the name "John Henry" at the time that those tunnels were being built. Though he could not find any documentary evidence, he believes on the basis of anecdotal evidence that the contest between man and machine did indeed happen at the Talcott, West Virginia site due to the presence of all three (a man named John Henry, a tunnel named Big Bend, and a steam-powered drill) at the same time at that place.<sup>1</sup>. | ||

The part-time folklorist John Garst has argued that the contest instead happened at the [[Coosa Tunnel]] or the [[Oak Mountain Tunnel]] of the [[Columbus and Western Railway]] (now part of [[Norfolk Southern Railway|Norfolk Southern]]) near [[Leeds]] on September 20, [[1887]]. | The part-time folklorist John Garst has argued that the contest instead happened at the [[Coosa Tunnel]] or the [[Oak Mountain Tunnel]] of the [[Columbus and Western Railway]] (now part of [[Norfolk Southern Railway|Norfolk Southern]]) near [[Leeds]] on [[September 20]], [[1887]]. Based on railroad documents that correspond with the account of C. C. Spencer, who claims to have witnessed the contest, he speculates that John Henry may have been a man named Henry who was born a slave, owned by [[P. A. L. Dabney]], the father of the chief engineer of that railroad, in [[1844]].<sup>2</sup> The city of Leeds honored John Henry's legend with an exhibit in its [[Bass House]] historical museum and held the first [[John Henry Days]] festival on [[September 20]], [[2007]].<sup>3</sup> In [[2008]], John Henry Days was incorporated into the inaugural [[Leeds Folk Festival]], set to be an annual event. | ||

While | Gart's version of the legend is undermined by the fact that John Henry appeared in ballads in the 1870s, before the event he documented in Leeds. Researcher Scott Reynolds Nelson proposes that clues from the earliest documented versions of the song, such as the line, "They took John Henry to the white house, and buried him in the sand," point to the Virginia State Penitentiary, which housed black convicts in a white-painted bunkhouse and [[convict lease system|leased]] their labor to the C&O Railway. Nelson uncovered records of a John William Henry who was sent to work at the Lewis Tunnel in West Virginia in the 1870s, and verified that steam hammers were tested at that site in the same period. The fact that there is no record at the prison of his death or release suggests to Nelson the possibility that he died while he was in the railroad's custody. | ||

While the legend of John Henry may or may not be factual, the story made Henry an important symbol of the working man, an archetype of the tragic futility of resisting the loss of traditional labor roles to new technologies in the 19th century. Some labor advocates interpret the legend as saying that even if you are the most heroic worker of time-honored practices, management remains more interested in efficiency and production than in your health and well-being; though John Henry worked himself to death, they replaced him with a machine anyway. Thus the legend of John Henry has been a staple of leftist politics, labor organizing and American counter-culture for well over a hundred years. | |||

==In popular culture== | ==In popular culture== | ||

Many versions of the John Henry ballad have been recorded by blues, folk, and rock musicians, including Leadbelly, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, Mississippi John Hurt, Woody Guthrie, [[Big Bill Broonzy]], [[Odetta]], Johnny Cash, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Fred McDowell, John Fahey, Harry Belafonte, Roberta Flack, Dave Van Ronk, and the [[Drive-By Truckers]]. | |||

Henry was the subject of the 1931 Roark Bradford novel ''John Henry'', illustrated by noted woodcut artist J. J. Lankes. The novel was adapted into a stage musical in [[1940]], with Paul Robeson starring in the title role. | |||

In [[1996]] the U.S. Postal Service issued a 32-cent first-class stamp with a painting of John Henry by David LaFleur. | |||

In [[2000]], Walt Disney | In [[2000]], Walt Disney produced a short animated film based on John Henry, written by Shirley Pierce and directed by Mark Henn. The creators collaborated with the Grammy Award winning group "The Sounds of Blackness" to create all new songs for the film. The film was one of seven finalists for the 2001 academy awards in its category, but was not given a wide theatrical release. A slightly cut-down version was included in the [[2001]] video compilation ''Disney American Legends'' and has been made available to schools and shown on the Disney Channel. | ||

The John Henry legend and its place in contemporary society is the focus of Colson Whitehead's 2001 novel ''John Henry Days'', which was shortlisted for a Pulitzer Prize. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 22: | Line 30: | ||

# Long, Roy C. (1991) "Big Bend Times". ''C&O History'' | # Long, Roy C. (1991) "Big Bend Times". ''C&O History'' | ||

# Garst, John (2002). "Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress". ''Tributaries: Journal of the Alabama Folklife Association''. No. 5. pp. 92–129 | # Garst, John (2002). "Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress". ''Tributaries: Journal of the Alabama Folklife Association''. No. 5. pp. 92–129 | ||

# Thornton, William (September 3, 2006) "Leeds' plans for saluting Henry." '' | # Thornton, William (September 3, 2006) "Leeds' plans for saluting Henry." {{BN}} | ||

* Nelson, Scott Reynolds (2006) ''Steel Drivin{{'}} Man: John Henry: The Untold Story of an American Legend.'' New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195300109 | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 30: | Line 39: | ||

*[http://www.newhouse.com/archive/story1c012402.html Folklore Researcher Places Legendary John Henry in Alabama] | *[http://www.newhouse.com/archive/story1c012402.html Folklore Researcher Places Legendary John Henry in Alabama] | ||

[[Category:Folk heroes | {{DEFAULTSORT:Henry, John}} | ||

[[Category:Leeds | [[Category:Folk heroes]] | ||

[[Category:Railroad workers | [[Category:Leeds]] | ||

[[Category:Railroad workers]] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:05, 29 January 2022

- This article is about the folk hero. For the former CFO of the Jefferson County Finance Department, see John Henry (CFO).

John Henry is an African-American folk hero who has been the subject of numerous songs, stories, plays, and novels.

Like other "Big Men" such as Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, and Iron John, John Henry served as a mythical representation of a particular group within the melting pot of the 19th-century working class. In the most popular story of his life, Henry was born into the world big and strong. He grew to be one of the greatest "steel-drivers" in the railroad-building age. As the story goes, the owner of the railroad bought a steam-powered hammer to do the work of his driving crew. In a bid to save his job and the jobs of his men, John Henry challenged the machine to a contest. John Henry out-muscled the steam hammer, but in the process, he succumbed to exhaustion and died. Older songs refer to him driving blasting holes into rock rather than driving spikes into rail ties.

The truth about John Henry is obscured by time and myth, but one account identifies him as a slave born in Alabama in the 1840s who fought his famous battle with the steam hammer along the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in Talcott, West Virginia. A statue and memorial plaque have been placed along a highway south of Talcott as it crosses over the tunnel in which the competition may have taken place.

The railroad historian Roy C. Long found that there were multiple Big Bend Tunnels along the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway. Also, the C&O employed multiple black men who went by the name "John Henry" at the time that those tunnels were being built. Though he could not find any documentary evidence, he believes on the basis of anecdotal evidence that the contest between man and machine did indeed happen at the Talcott, West Virginia site due to the presence of all three (a man named John Henry, a tunnel named Big Bend, and a steam-powered drill) at the same time at that place.1.

The part-time folklorist John Garst has argued that the contest instead happened at the Coosa Tunnel or the Oak Mountain Tunnel of the Columbus and Western Railway (now part of Norfolk Southern) near Leeds on September 20, 1887. Based on railroad documents that correspond with the account of C. C. Spencer, who claims to have witnessed the contest, he speculates that John Henry may have been a man named Henry who was born a slave, owned by P. A. L. Dabney, the father of the chief engineer of that railroad, in 1844.2 The city of Leeds honored John Henry's legend with an exhibit in its Bass House historical museum and held the first John Henry Days festival on September 20, 2007.3 In 2008, John Henry Days was incorporated into the inaugural Leeds Folk Festival, set to be an annual event.

Gart's version of the legend is undermined by the fact that John Henry appeared in ballads in the 1870s, before the event he documented in Leeds. Researcher Scott Reynolds Nelson proposes that clues from the earliest documented versions of the song, such as the line, "They took John Henry to the white house, and buried him in the sand," point to the Virginia State Penitentiary, which housed black convicts in a white-painted bunkhouse and leased their labor to the C&O Railway. Nelson uncovered records of a John William Henry who was sent to work at the Lewis Tunnel in West Virginia in the 1870s, and verified that steam hammers were tested at that site in the same period. The fact that there is no record at the prison of his death or release suggests to Nelson the possibility that he died while he was in the railroad's custody.

While the legend of John Henry may or may not be factual, the story made Henry an important symbol of the working man, an archetype of the tragic futility of resisting the loss of traditional labor roles to new technologies in the 19th century. Some labor advocates interpret the legend as saying that even if you are the most heroic worker of time-honored practices, management remains more interested in efficiency and production than in your health and well-being; though John Henry worked himself to death, they replaced him with a machine anyway. Thus the legend of John Henry has been a staple of leftist politics, labor organizing and American counter-culture for well over a hundred years.

In popular culture

Many versions of the John Henry ballad have been recorded by blues, folk, and rock musicians, including Leadbelly, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, Mississippi John Hurt, Woody Guthrie, Big Bill Broonzy, Odetta, Johnny Cash, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Fred McDowell, John Fahey, Harry Belafonte, Roberta Flack, Dave Van Ronk, and the Drive-By Truckers.

Henry was the subject of the 1931 Roark Bradford novel John Henry, illustrated by noted woodcut artist J. J. Lankes. The novel was adapted into a stage musical in 1940, with Paul Robeson starring in the title role.

In 1996 the U.S. Postal Service issued a 32-cent first-class stamp with a painting of John Henry by David LaFleur.

In 2000, Walt Disney produced a short animated film based on John Henry, written by Shirley Pierce and directed by Mark Henn. The creators collaborated with the Grammy Award winning group "The Sounds of Blackness" to create all new songs for the film. The film was one of seven finalists for the 2001 academy awards in its category, but was not given a wide theatrical release. A slightly cut-down version was included in the 2001 video compilation Disney American Legends and has been made available to schools and shown on the Disney Channel.

The John Henry legend and its place in contemporary society is the focus of Colson Whitehead's 2001 novel John Henry Days, which was shortlisted for a Pulitzer Prize.

References

- "John Henry (folklore)." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 8 Sep 2006, 02:39 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 8 Sep 2006 [1].

- Long, Roy C. (1991) "Big Bend Times". C&O History

- Garst, John (2002). "Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi: A Personal Memoir of Work in Progress". Tributaries: Journal of the Alabama Folklife Association. No. 5. pp. 92–129

- Thornton, William (September 3, 2006) "Leeds' plans for saluting Henry." The Birmingham News

- Nelson, Scott Reynolds (2006) Steel Drivin' Man: John Henry: The Untold Story of an American Legend. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195300109

External links

- John Henry - The Steel Driving Man Includes a page with the updated abstract of Garst (2002) above.

- John Henry, Present at the Creation

- John Henry Statue at Heritagepreservation.org

- Folklore Researcher Places Legendary John Henry in Alabama