Art Hanes

Arthur Jackson Hanes Sr (born October 19, 1916; died May 8, 1997) was the 21st Mayor of Birmingham, serving as president of the Birmingham City Commission from 1961 until the change to a Mayor-Council form of government in 1963.

Hanes was a notable opponent of racial integration in Birmingham, but he also opposed the high-profile, heavy-handed style of his colleague, Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor. Hanes' administration closed Birmingham's city parks rather than comply with a federal judge's order to integrate them. A referendum which changed Birmingham's government to a Mayor and City Council in 1963 opened the way for the election of moderate Albert Boutwell. Hanes and his fellow commissioners fought the change, but finally surrendered his office on April 23.

After leaving office, Hanes remained a popular figure in the segregationist movement, headlining public rallies. In 1977 he was the lead attorney in Robert Chambliss' unsuccessful defense against new charges brought against him from the 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church.

Early life and career

Hanes was the son of a Methodist minister James Oscar Hanes and the former Emma Barton. He played baseball and football while a student at Woodlawn High School and Birmingham-Southern College. For the BSC Panthers football team he starred as a fullback with the nickname "Chicken". After graduating from law school he became an FBI agent in Washington D.C. and Chicago, Illinois. He returned to Birmingham as chief of security for the Hayes Aircraft Corporation under Lew Jeffers. It fell to him, as a former FBI agent and colleague of the airmen, to clandestinely inform the families of the four U.S. pilots shot down in the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

Hanes represented Eastern Birmingham on the Birmingham Board of Education in the late 1950s. A vocal proponent of racial segregation, Hanes served as master of ceremonies for a large meeting of Alabama's White Citizens Councils at Municipal Auditorium in 1955 and also spoke to gatherings of the John Birch Society.1.

Mayoral campaign

Hanes was recruited to run for President of the Commission after Jimmy Morgan stepped down2.. His strongest opponent in the race was Tom King. Hanes won the endorsement of the Birmingham News. In the May 2 primary King garnered 1,500 more votes than Hanes, who came in second in the field of seven.

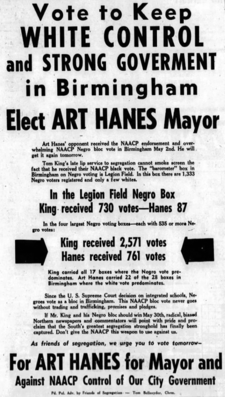

Hanes' campaign was helped by unofficial supporters who were free to exploit racial tension in the city. Before the runoff, flyers from the Committee to Keep Birmingham White claimed that King was funded by the NAACP and that his campaign pledge to upgrade the city's airport was a step down Atlanta's accommodationist path3.. On May 8 King met with Connor at Birmingham City Hall and was caught in a staged photograph shaking hands with a black man. According to rumors, the man had been paid $20 by City Hall staffer Clint Bishop to grab at the candidate as he left the building.4. The News switched its support to King the following Sunday, May 14, blaming Hanes for raising the "scarecrow" of race divisions5..

Tensions over integration were raised even higher later that day by the arrival of Freedom Riders at the Trailways Bus Station. Under Connor's direction, Birmingham Police delayed their arrival, giving gathered anti-integration vigilantes several minutes to viciously beat the Freedom Riders without interference. King spoke out against the violence while Hanes pledged "if my opponent is elected tomorrow that this will be hailed as the fall of the South's greatest segregation stronghold."6.

In the May 30 runoff Hanes beat King 21,133 to 17,385.

Mayor of Birmingham

In his inaugural address of November 6, Hanes voiced support for proposals to merge nearby suburbs into Birmingham to foster economic growth (an idea later defeated as the One Great City campaign). He later opposed efforts to incorporate all of Jefferson County under a unified government, and was less than enthusiastic about absorbing the public debt of Mountain Brook while predicting that unless at least some of the white suburbs could be annexed, that continued white flight would insure that, "an undesirable class will gain control of Birmingham."7.

The first major action of the new Commission was to hold good on a threat made in the final days of Morgan's administration to close all public parks rather than comply with an order from Judge Hobart Grooms that they would have to be integrated.8. In April 1962 the City Commission responded to a boycott of downtown stores by pulling support for a food distribution program operated by Jefferson County which largely benefitted black families. Hanes suggested that if the NAACP was directing African Americans to protest that it could take charge of feeding them, too.9.

Also in 1962, Hanes appointed a commission to plan for implementation of the 1961 Birmingham comprehensive plan for massive redevelopment of the City Center with elevated pedestrian skyways.10.

At the beginning of his administration, the unpopular park closing had prompted the formation of a coalition of "business progressives" desperate to prevent more "black eyes" for the city. In a July 1962 interview, Birmingham Post-Herald columnist James Jones referred to the policy of "token" integration which had apparently succeeded in limiting bad publicity and racial tension in Atlanta. Hanes responded that, "as far as I'm concerned there's a great principle involved and I'm not willing to yield."11.

Sidney Smyer chaired a landmark bi-racial meeting on December 1. Hanes, who had pledged during his campaign to "sit down and talk to any group" was invited to attend, but declined. The conference was ineffective at bridging the widening gap between the races, but it did lead toward efforts to change the city's form of government under the banner of progress. That campaign gathered enough petition signatures to force a referendum on November 6, 1962. The decision to change was made by a margin of 700 votes. Hanes declined to throw his hat into the race for Mayor, set for April 2, 1963, just as the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were finalizing plans for their Birmingham campaign of mass demonstrations.

The sitting commission refused to leave office when new Mayor Albert Boutwell and the first Birmingham City Council were sworn in on April 15, claiming that by law they had been elected to serve full four-year terms. Until Judge Edgar Bowron ruled against the Commission on April 23 the city had two governments acting in parallel, sharing City Hall and taking up the same agendas. It was during that period that the most intense confrontations of "Project C" were taking place on the streets and despite the confusion, Connor clearly controlled the city's physical response to the demonstrators.

| Preceded by: Jimmy Morgan |

Mayor of Birmingham 1961–1963 |

Succeeded by: Albert Boutwell |

Later life

After leaving the mayor's office Hanes remained a popular speaker for anti-integration groups. When Birmingham City Schools were set to be integrated in the fall of 1963, he was quoted as saying, "I would like to see a solid wall of white citizens around the schools when the Negroes try to get in."12. He supported a movement led by Raymond Rowell to once again petition for a referendum on the city's form of government, unsuccessfully seeking a return to the Commission system.13. In another speech, he lambasted the Methodist church for including a quotation from W. E. B. DuBois in one of its publications. He declared that DuBois had, "a long and sordid record of affiliations with pro-Red groups."14.

Hanes also returned to the practice of law, earning acquittals for Klansmen accused of murdering civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo, briefly defending James Earl Ray in 1968, and defending Bob Chambliss in the murder trial brought in 1970 against the men suspected in the 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church.

Hanes died in 1997. He was survived by two sons, Art Jr and Thomas. He was buried at Elmwood Cemetery. Art Hanes Boulevard and Art Hanes Circle off Montclair Road were named in his honor by the developer, who was a member of his Sunday school class at East Lake United Methodist Church.15.

Notes

- McWhorter-2001, p. 181

- McWhorter, Diane (May 30, 1984) Interview with James Head, cited in McWhorter-2001, p. 180

- Morgan, Charles (1964) A Time to Speak. New York, New York: Harper & Row, cited in McWhorter-2001, p. 196

- McWhorter-2001, p. 197

- Birmingham News (May 14, 1961), quoted in Nunnelly-1991, p. 94

- Birmingham News (May 31, 1961), quoted in Nunnelly-1991, p. 111 and McWhorter-2001, p. 243

- Jones-1962

- Birmingham News (December 9, 1961), quoted in Nunnelly-1991, p. 114

- Eskew, Glenn T. (1987) The Alabama Christian Movement and the Birmingham Struggle for Civil Rights, 1956-1963. M.A. thesis, University of Georgia, cited in Nunnelly-1991, p. 122

- Connerly-2005, p. 205

- Jones-1962

- Nunnelly-1991, p. 172

- Hanes-1963

- Brown-1963

- Garrison-2020

References

- Jones, James (July 17, 1962) "Too Far Reaching-- Mayor Opposes Metro Proposal" Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Hanes, Arthur J. (August 25, 1963) "Voice of the People: Hanes Replies to Critic" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Brown, Don (August 25, 1963) "Birmingham totters on the mixing brink" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Nunnelly, William A. (1991) Bull Connor. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817304959

- "Art Hanes, 80, Mayor Who Closed Birmingham Parks to Bar Blacks." (May 10, 1997) New York Times

- McWhorter, Diane (2001) Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0743226488

- Connerly, Charles E. (2005) The Most Segregated City in America: City Planning and Civil Rights in Birmingham, 1920-1980. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813923344

- Solomon, Jon (February 20, 2013) "Art Hanes Jr.: Son of segregationist Birmingham mayor says dad privately tried to integrate." The Birmingham News

- Garrison, Greg (July 30, 2020) "Birmingham firefighter asks why segregationist mayor has streets named for him." The Birmingham News