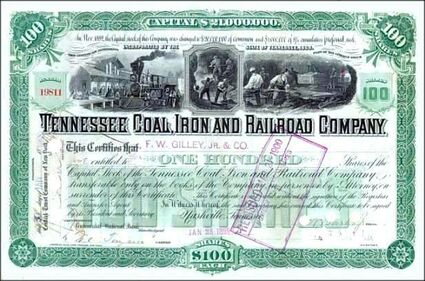

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely within the state of Tennessee, it relocated its headquarters to Birmingham in 1895, from then onwards operating almost exclusively around the Birmingham region. With a sizable real estate portfolio, it owned the Birmingham satellite towns of Ensley and Fairfield, where it located two large steel mills, the latter employing a peak of upwards of 4500 workers during World War II.

At one time the second largest steel producer in the USA in terms of assets and output, TCI was listed on the first Dow Jones Industrial Average index in 1896. This brought it into direct competition with its principal rival, the United States Steel Corporation, with which it merged in 1907 after banker J.P. Morgan exploited turbulence on the financial markets by procuring a majority stake in Tennessee Company shares from a troubled New York brokerage firm. Subsequently, Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad operated as a subsidiary of U.S. Steel for 45 years, until it became a division of its parent company in 1952. The Tennessee Coal & Iron Division of U.S. Steel continues to operate the Fairfield steel plant to this day as the largest such steel works in Alabama, with a total output of 2.4 million tonnes of raw steel per annum.

History

Early history

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad was founded as the Sewanee Furnace Company,1 a small mining concern established in 1852 by Nashville entrepreneurs1 seeking to exploit Tennessee's rich coal reserves and the 19th century railroad boom. After losing money the business was sold to New York investors in 1859, and was reorganized as the Tennessee Coal and Rail Company,1 but the outbreak of the Civil War the following year and the severing of ties between North and South saw the fleeting company repossessed by local creditors. It became Tennessee's leading coal extractor over the next decade,1 mining and transporting coal around the towns of Cowan and Tracy City in the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee,2 and soon branched out into coke manufacture.1 This practice of both extracting and moving coal to market by building private rail tracks was not unusual at the time, as by owning the tracks that served their mines businesses could undercut rivals at market by saving money on transportation. It is worth noting that it was through this method that the hugely successful Standard Oil Trust gained a near-monopoly in the petroleum industry during the same period, though John D. Rockefeller never owned the rails, he merely extracted concessions from their owners. A Thomas O'Connor purchased the company in 1876 and expanded the business into iron manufacture in order to stimulate coke sales, building a blast furnace near Cowan.1 The business was subsequently renamed the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company.

In 1886 the Tennessee Coal Iron & Railroad Company purchased the Birmingham-based Pratt Coal & Iron Company from Enoch Ensley, who was subsequently made president of the Tennessee Company. By 1888 the company was comprised of five divisions: The Birmingham Division, which operated the two Alice Furnaces (180 tons/day capacity) and Linn Iron Works; the Pratt Mines Division, supplying most of the district with coal and coke; the Ensley Division, with four furnaces at the Ensley Works (600 tons/day capacity); the South Pittsburgh Division with three furnaces in Pittsburgh, Tennessee and the Cowan Division with one furnace and mines in Cowan, Tennessee. The vice-president in Birmingham was T. T. Hillman.

In 1895 the company moved its headquarters to Birmingham, signaling the relative unimportance of operations in the company's native state.2

Canny investments and the purchase of major competitors in 1888 and 1892, under the direction of financier Hiram Bond, TCI Corporate General Superintendent, saw the firm rapidly grow. The corporation was for several decades one of the few major successful heavy industries based in the largely agricultural and textile-dependent postbellum Southern United States,3 by a wide margin the largest blast furnace operator in the South and at one time the second largest steel producer on the continent.23 Its 1900 asset sheet listed 17 blast furnaces, 3256 beehives and 120 Solvay coke ovens, 15 red ore mines (in the Birmingham District only - by 1899 the company had successfully researched how to effectively utilize the high-phosphorus Birmingham district ore and ceased to utilize Tennessee iron),2 as well an extensive network of railroads.

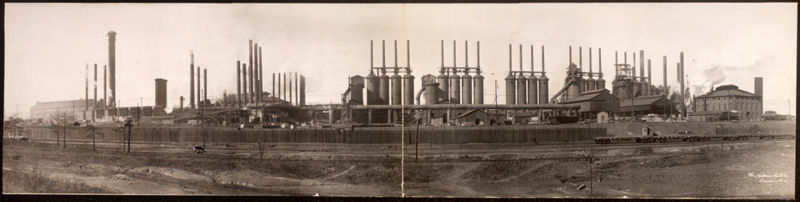

Following the Panic of 1893 the company shifted its primary interests from railroads to steel.1 The TCI's largest industrial plant was located in Ensley, a company town founded in 1886 on the outskirts of Birmingham by Memphis entrepreneur and first president of Tennessee Coal, Iron and Rail, Enoch Ensley. Ensley (map of) was served by the company's railroads, namely the sizable Birmingham Southern Railroad, which TCI had just purchased, and from 1899 contained four 200-ton blast furnaces. In 1906 two more furnaces were constructed and 40,000 tonnes of steel were produced that year, feeding Ensley's integrated rail, wire and plate mills. The company was fiercely competitive with the larger Pittsburgh steel companies to the north, owing to the remarkable fact that all the natural resources required to produce steel were located in abundance within a relatively small radius of the Birmingham mills.4

Listing on the Dow Jones Index and merger with US Steel

The Tennessee Company's status was bolstered when it became one of the first 12 companies to be listed on the inaugural Dow Jones Industrial Average index compiled in May 1896.5 The size of TCI, as well as its enviable position on the exclusive Industrial Average, attracted the attention of banker and tycoon J.P. Morgan and his recently formed conglomerate, the United States Steel Corporation, the USA's leading steel producer and the successor to the enormous Carnegie and Federal steel empires. Morgan launched a takeover bid in a unique power play by exploiting a sudden financial panic in 1907, a period of intense financial turmoil which saw numerous runs on banks, an economic recession and a halving of the value of the New York stock market from its 1906 peak.6

During the height of the crisis, concern arose regarding a wealthy Wall Street investment banking firm, Moore and Schley. The company was heavily involved in a large speculative pool operation in Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad, and had secured huge loans from the major Wall Street banks against 6 million TCI shares.6 As the nervous banks began to call these loans in, the firm found that the tumbling price of its shares had left it insolvent.7 Morgan recognized that if Moore and Schley failed and confidence in the nation's economy took a further dive, hundreds more business failures would follow and the consequences would be catastrophic. Morgan resolved to aid the company and hastily requested that U.S. Steel purchase Moore's $30 million stake in Tennessee Company stock in order to inject liquidity into the firm.6

Morgan's altruism should not be overplayed. TCI was U.S. Steel's largest competitor at the time8 and controlled lucrative coal and ore deposits. Hence Morgan's proposition, which amounted to the sale of TCI to U.S. Steel, would be to his own personal advantage as a major shareholder in U.S.S Corp. E. H. Gary, president of U.S. Steel, agreed in principle to the acquisition, yet argued that without careful political maneuvering the deal would encounter troublesome federal anti-trust litigation.6 His corporation dominated the American steel industry at the time, regardless of any further expansion, and had always maneuvered with care to avoid the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. The purchase of TCI would undoubtedly be seen as an effort to create a monopoly. Morgan himself knew all too well the power of the Act - one of his earlier combinations, the Northern Securities Company, had met its fate at its hands in a landmark test case.8 In response to his concerns, Morgan sent Gary to negotiate the deal with President Theodore Roosevelt himself,6 encouraging his colleague to lie extensively about the nature of the merger8 (which he euphemistically called a 'public service')2 in order to allay the fears of the president, a notorious 'trust buster', that the deal would be to the detriment of the American steel industry and the nation's economy as a whole. Roosevelt was convinced to grant the transaction antitrust immunity, a decision which, after the mania and desperation of the panic had calmed, attracted extreme anxiety amongst the population and saw Roosevelt heavily criticized for.7 Indeed, in 1911 the federal government sought to undo what it perceived to be Roosevelt's mistake and (without success) attempted break U.S. Steel up. In the mean time, Moore and Schley was saved from collapse, the panic immediately subsided6 and Morgan was rewarded with a valuable prize - a controlling majority in TCI. U.S. Steel immediately replaced Tennessee Coal, Iron and Rail on the Dow Jones Index, where it remained until 1991.9

Division of U.S.S. Corp.

TCI was not fully incorporated into the U.S.S Corp., and continued to operate as an extremely profitable8 subsidiary of its parent company well into the 20th century. Immediately following the merger, former National Tube Company manager George Crawford was made president of TCI.

Crawford oversaw the conglomerate's major investments in TCI industrial properties, and also headed an elaborate social welfare program aimed at improving the division's labor force. In 1910, work began to create a new, larger TCI plant at the center of a new company town west of Ensley, initially named "Corey" after an executive who later committed suicide, prompting it to be renamed Fairfield2. The steel works there opened in 1917. With the discovery of new coking coal and ore deposits in the region, and with the aid of U.S. Steel's enormous capital, the Fairfield works were quickly expanded with the construction of new steel mills and rail links. Notable developments included the completion of several rolling mills in 1917,2 which produced ship materials for the nearby shipbuilding plants in Chickasaw, in support of America's sudden entry into World War I. In 1920 a direct rail line between Fairfield and Birmingport, the new port of Birmingham on the Warrior River was opened.2 This was followed by the completion of the High Ore Line Railroad,2 connecting Red Mountain and the Fairfield works. Trains literally rolled down the hill from mine to mill. In 1923 a merchant steel mill was completed,2 followed by the opening of a sheet products mill in 1926.2

TCI proved to be so efficient at making cheap steel that a post-merger internal tariff (the 'Pittsburgh Tariff') was levied by U.S. Steel in 1909 against all steel coming out of the Birmingham region. This was an effort to negate the competitive edge of Birmingham steel over U.S. Steel's own Pittsburgh product.4

TCI's independence as a separate legal entity from its parent corporation ended in 1952, a century after the founding of the Sewanee Furnace Company, when the it became the Tennessee Coal & Iron Division of U.S. Steel.2 The memory of the historic importance of TCI was not lost when, in 1960, a short book to celebrate the Tennessee Company's centenary was published by U.S.S. Corp.: Biography of a Business.2 Decline began in 1962 when a majority of the mines in the Birmingham region were closed2 as cheap Venezuelan ores and foreign coal began to be favored by the steel business. The 1970s and 80s brought about a downsizing and eventual consolidation of the Fairfield and Ensley works,2 mirroring the general decline of heavy industry in the USA throughout those decades.

The Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company's longest-lasting legacy, the massive Fairfield Works, was shuttered in 2015.

References

- Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company. (April 9, 2009). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed May 13, 2009.

- Hillstrom, Kevin; Laurie Collier (2005). The Industrial Revolution in America: Iron and Steel, Railroads, Steam Shipping. ABC-CLIO. pp. 71. ISBN 1851096205.

- John Stewart (2006-07-15). "Capital Improvements and Corporate Development Timeline for TCI with selected parallel local developments in the Birmingham District". Retrieved on 2008-05-10.

- Encyclopedia Britannica (2008-05-10). "Furnaces of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company, Ensley, Alabama, 1906". Retrieved on 2008-05-10.

- John Stewart (2006-07-15). "Birmingham Rails, TCI & RR section, p2". Retrieved on 2008-05-10.

- djindixes.com (2008-05-10). "What happened to the original 12 companies in the DJIA?". Retrieved on 2008-05-10.

- Citizendium (2007-12-06). "Panic of 1907". Retrieved on 2008-05-12.

- Markham, Jerry W. (2002). A Financial History of the United States. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765607301.

- Brogan 1999 p445

- Global Financial Data (2008-03-28). "Dow Jones Industrial Average History". Retrieved on 2008-05-11.

- "Report on the Fairfield Plant". 2008-05-10. Retrieved on 2008-05-10.

- Paul V. Arnold (2006-09-01). "U.S. Steel's Fairfield Works". Retrieved on 2008-05-11.

- U.S. Steel (2006-07-25). "U.S. Steel Fairfield Works". Retrieved on 2008-05-11.

Further reading

- Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company: Description of Plants and Mines with Illustrations (July 1900) Birmingham: Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Co./New York: Isaac H. Blanchard Co.

- Biography of a Business (1960) United States Steel Corporation ISBN B000R2Q8CU

- Birmingham Rails: Yesterday and Today

- Brogan, Hugh (1999). The Penguin History of the USA. Penguin. ISBN 13 978-0-140-25255-2.