Willie Mays

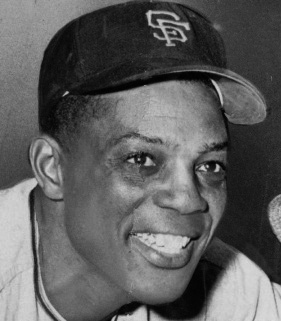

Willie Howard Mays Jr (born May 6, 1931 in Westfield) is a former baseball player who was twice named National League player of the year, appeared in 24 All-Star Games, won 12 Gold Gloves, and was inducted to the Baseball Hall of Fame on the first ballot after becoming eligible in 1979.

Mays, the son of Negro League baseball player Willie "Cat" Mays and high school sprinter Annie Satterwhite, was recognized early in life as a gifted athlete. His parents never married and he was raised largely in Fairfield by his aunts, Sarah and Ernestine. His father taught him to play ball, and he actually played first base for two innings for his father's Fairfield Stars when he was 10 years old. He starred in baseball, football and basketball at Fairfield Industrial High School while continuing to play with the Stars in the Industrial Leagues.

In 1946 the then 15-year-old Mays made his professional debut with the New York Cubans. He played with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos some the next season before joining the Birmingham Black Barons as a $250 per month part-timer. He played baseball on weekends and continued his schooling during the week. He helped the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons to a 55-21 record and the Negro American League pennant. The Black Barons lost the final Negro Leagues World Series to the Homestead Grays.

Under the tutelage of the Black Barons' Piper Davis, Mays developed into a powerful and patient hitter. His batting average rose to .311 in 1949 and .330 in 1950. On the day he graduated from high school that year he signed a $15,000 per year contract with the New York Giants. He spent two years with the Trenton Giants and Minneapolis Millers. After 35 games with the AAA Millers in 1951 he was hitting .477 and earned his call up to Polo Grounds to play in the big leagues.

Mays debuted on May 25, 1951 but went hitless in his first 13 at bats. On his 14th trip to the plate, he homered off Warren Spahn before returning to his rookie slump. Giants manager Leo Durocher had confidence in his young center fielder. After 121 games he was hitting .274 with 20 home runs and 68 runs batted in. It was his brilliant fielding, however, that contributed to his winning the National League's Rookie of the Year award and to the Giants' claiming the pennant from their rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers.

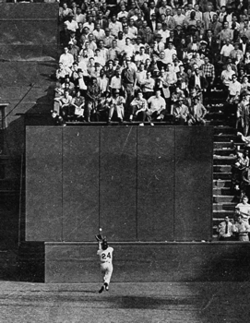

In 1952 Mays was drafted into the Army. He played on baseball teams at Fort Eustis in Newport News, Virginia but was never sent overseas. Upon his return to the Giants he enjoyed a stellar 1954 season, batting .345 with 41 home runs, 110 runs batted in and 119 runs scored. He was the league's Most Valuable Player and led the Giants to a World Series title over the Cleveland Indians. His over-the-shoulder running catch of Vic Wertz's long hit, followed by a quick-turnaround that prevented a runner from scoring, is still remembered as "The Catch". After the "Gold Glove" award was created in 1957, Mays won 12 consecutive times.

In 1958 the Giants relocated to San Francisco, California. They won another pennant in 1962 and made Mays their team captain, the first African American so honored in the major leagues, in 1964. He was named the National League's most valuable player for the second time that year. He was also asked by teammate Bobby Bonds to serve as godfather to his son, Barry.

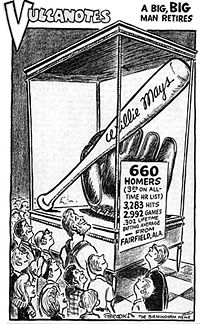

In 1966 Mays signed a contract making him this highest-paid player in baseball history. He hit his 500th career home run in 1969, and was the first player to surpass 3,000 hits and 500 home runs for his career (two peak years of which were lost to his military service). The Sporting News named him their "Player of the Decade" for the 1960s. In 1972 the aging star was traded to the New York Mets where he played two seasons as a part-time first baseman. He broke Stan Musial's record for the most All-Star nominations in 1973 and announced his retirement later that year.

Mays finished his career with 660 home runs, 3,283 hits, 1,903 runs batted in, 338 stolen bases, and a career batting average of .302. As a fielder he recorded 7,752 put outs with 156 errors, with a 0.981 fielding percentage. He remained with the club as a hitting coach until 1979.

After baseball

1979 marked a high and a low for Mays' legacy. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, but also banned from the sport by commissioner Bowie Kuhn for working as a greeter at the Park Place Casino in Atlantic City. He was reinstated, along with Mickey Mantle, by Peter Ueberroth in 1985. The following year he was hired as a Special Assistant to the President of the San Francisco Giants.

Mays had never been formally celebrated in his home town. He did visit as a guest of Mayor George Seibels to speak at a Youth Opportunity Drive in Collegeville and Marks Village in 1968, but turned down many other invitations. He was even absent when he was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 1977. On October 31, 1981 visited Birmingham for Willie Mays Day, highlighted by a parade and the presentation of a key to the city during halftime of the Magic City Classic. Since then he has returned to the Classic as its "ambassador" in 2000 and served as a host of a February 26, 2006 throwback game produced by ESPN at Rickwood Field with amateur players in the uniforms of the Birmingham Black Barons and Bristol Barnstormers. Mays has been supportive of efforts to develop a Negro Leagues Museum in the city.

He was also a member of the inaugural class of the Birmingham Barons Hall of Fame in 2005. Mays' jersey number, 24, is used throughout the Giants' AT&T Park, the address of which is "24 Willie Mays Plaza". The right-field wall of the stadium is 24-feet tall. A 9-foot-tall bronze statue of Mays stands outside the stadium. May 24 is celebrated as "Willie Mays Day" in San Francisco. In New York, the service road connecting Harlem River Drive between 155th and 163rd Streets near the Polo Grounds was dedicated as "Willie Mays Drive" in 2008. Mays was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama on November 24, 2015.

Locally, the former 66th Street Park in Fairfield was re-named in his honor in 1985 and a two-block section of 1st Avenue South fronting Regions Field was renamed "Willie Mays Drive" in 2016. Also in 2016, a portrait statue of Mays making "The Catch", by Caleb O'Connor and Craig Wedderspoon, was installed on the 14th Street South side of the ballpark. The commission honored Birmingham Barons owner Don Logan as part of the Alabama-Mississippi Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society's "Legacy of Leadership" series.

In 2000 Mays served as Ambassador for the Magic City Classic at Legion Field.

References

- Mays, Willie & Charles Einstein (1966) Willie Mays: My Life In and Out of Baseball. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc.

- Linge, Mary Kay (2005) Willie Mays: A Biography. New York: Greenwood Press

- Hirsch, James S. (2010) Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend. New York: Scribner. ISBN 1416547907

- Ruffin, Herbert G. (October 8, 2010) "Willie Mays". Encyclopedia of Alabama - accessed May 27, 2011

- "Willie Mays" (May 26, 2011) Wikipedia - accessed May 27, 2011

External links

- Willie Mays at baseball-reference.com

- Willie Mays' Hall of Fame induction speech at baseballhall.org