John Tyler Morgan: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''John Tyler Morgan''' (born June 20, 1824 in Athens, Tennessee; died June 11, 1907 in Washington D.C.) was a Confederate general, Klan leader and six-term U....") |

No edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

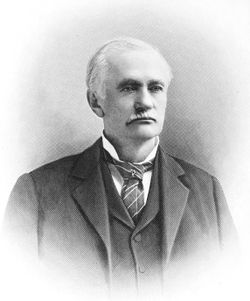

'''John Tyler Morgan''' (born [[June 20]], [[1824]] in Athens, Tennessee; died [[June 11]], [[1907]] in Washington D.C.) was a Confederate general, Klan leader and six-term U.S. Senator. | [[File:John Tyler Morgan.jpg|right|thumb|250px|John Tyler Morgan]] | ||

'''John Tyler Morgan''' (born [[June 20]], [[1824]] in Athens, Tennessee; died [[June 11]], [[1907]] in Washington D.C.) was a Confederate brigadier general, Klan leader and six-term U.S. Senator. | |||

Morgan was the son of George Washington and Mary Frances Irby Morgan. He was educated at home by his mother until moving with the family to [[Calhoun County]] in [[1833]], where he began attending a local frontier school taught by Charles Samuel. He continued his education by reading law under his brother-in-law, Judge [[William Chilton]], in [[Tuskegee]]. Upon his admission to the [[Alabama State Bar]] he opened a practice in [[Talladega]]. After a decade, he relocated to Selma, and also opened an office in the former capital of Cahaba. On [[February 11]], [[1846]] he married Cornelia Willis of Talladega County. They had five children, two of whom died as infants and were buried at their mother's family's [[Thornhill plantation]]. Their son, John H., died in a boating accident in the Potomac in 1885. Their oldest daughter, Mary, served as her father's secretary and died in North Carolina in 1909. The other daughter, Cornelia, lived to 1944. | |||

Morgan was | |||

Morgan was active in local politics and earned a position as an aid to prominent secessionist [[William Yancey]]. He was an elector at the Southern Democrats' convention in Baltimore, Maryland that nominated John C. Breckenridge for president in [[1860 general election|1860]]. He was also a delegate to the [[Alabama Secession Convention]] of January [[1861]]. | |||

During the [[Civil War]] Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, and was assigned to the [[5th Alabama Infantry (CSA)|5th Alabama Infantry]]. He participated in the first Battle of Manassas and was later promoted to Major and then to Lieutenant Colonel under Robert E. Rhodes. He resigned from service in [[1862]], but quickly returned to the war, helping organize the 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers and serving as its Colonel at the Battle of Murfreesborough. | |||

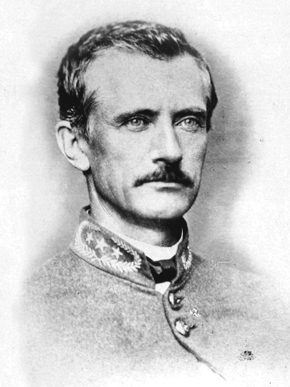

[[File:John Tyler Morgan CSA.jpg|left|thumb|Morgan during the Civil War]] | |||

Morgan declined an offer to follow Rhodes into the Army of Northern Virginia and remained in the west, commanding troops at the Battle of Chickamauga. He was promoted to Brigadier General, commanding the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 9th and 51st Alabama Cavalry regiments during the Knoxville Campaign. His forces were routed by Union cavalry on [[January 27]], [[1864]] and he was reassigned to the Atlanta Campaign, harassing federal troops under William T. Sherman during his "March to the Sea" across Georgia. Morgan spent the last days of the war attempting to organize former slaves into a home guard to oppose the depredations of occupation by Federal troops. | |||

Following the end of the war, Morgan resumed his practice in Selma. After [[James Clanton]] was killed in a duel in Knoxville, Morgan succeeded him as Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. He also returned to politics, aiding the state Democratic party in its successful efforts to retake the state legislature from Reconstruction Republicans in [[1875]]. | |||

In [[1876]] Morgan again served as an elector for Democrat Samuel Tilden, who won the popular vote but narrowly lost to Rutherford Hayes in the electoral college. Morgan was also elected by the [[Alabama State Legislature]] to represent the state in the U.S. Senate. The state's senior senator, [[George Spencer]], a native of New York elected by Alabama's Reconstruction legislature, moved to block his confirmation, but was unsuccessful. Morgan was re-elected in [[1882]], [[1888]], [[1894]] and [[1906]], serving from [[March 5]], [[1877]] until his death. | |||

[[ | |||

At various times during his five terms as Senator, Morgan chaired the Senate Rules Committee, the Foreign Relations Committee, the Committee on Inter-oceanic Canals and the Committee on Public Health and National Quarantine. He was known as a highly-intelligent debater, and once joked that with enough preparation he could talk for three days for or against a bill, but, if unprepared, he could continue indefinitely. | |||

Morgan | Morgan was among the Senate's most vocal white supremacists, supporting the proliferation of "Jim Crow" laws to reinstitute political and economic impotence and social segregation for African-Americans. His filibuster of the Federal Elections Bill of 1890, along with his numerous published writings on the subject, was credited with turning the public against the idea of having federal troops stationed at polling places to enforce voting rights. He was involved in efforts to repeal the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and to resettle African-Americans outside the continental United States. | ||

Morgan | At the same time, Morgan was a leader for Democrats championing the Monroe Doctrine. He pushed for expanded global trade, hoping to boost Alabama's economy through the export of cotton, coal, iron and timber to new overseas markets. To that end he supported enlargement of the U.S. Navy and merchant marine, and the annexation of far-flung territories as spoils from the [[Spanish-American War]]. He championed a planned canal through Nicaragua to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. That canal ultimately was constructed through the isthmus of Panama. Morgan was also a vocal supporter of José Martí's efforts to liberate Cuba from Spanish rule, with the hope that it would become part of the United States. | ||

Morgan also lobbied for reparations from the federal government to rebuild the campus of the [[University of Alabama]], which had been burned by U.S. troops in April [[1865]]. | |||

President Harrison appointed him as an arbiter in a controversy over Bering Sea fisheries in [[1892]]. In [[1894]] Morgan chaired the Senate investigation into the Hawaiian Revolution. He visited the Hawaiian islands in [[1897]] to support their annexation into the United States. President McKinley appointed him in July [[1898]] to the commission charged with establishing a territorial government in Hawaii. | |||

In June [[1907]] Morgan died in Washington D.C. three months after being sworn in for his fifth term in the Senate. [[John H. Bankhead]] of [[Jasper]] was appointed to fill his remaining term. In the House of Representatives on [[April 25]], [[1908]] Alabama congressman [[Tom Heflin]] remembered Morgan and his colleague, [[Edmund Pettus]], as men who did more than than any others to "stay the hideous tide of negro domination," by reversing Reconstruction-era political reforms. | |||

Morgan's body was transported to Selma for burial in that city's Live Oak Cemetery. Afterward the remains of his widow and son, who had predeceased him while they were living in Washington and had been buried in Rock Creek Cemetery there, were exhumed and re-interred alongside him in Selma. They were joined by the younger daughter Cornelia after her death in 1944. | |||

Shortly after his death, the newly-completed [[Morgan Hall]] at the University of Alabama was named in Senator Morgan's honor. He was inducted into the [[Alabama Hall of Fame]] in [[1953]]. Selma's John T. Morgan Academy, founded in [[1965]] as a "segregation academy," was named for the former Senator and held its first classes in his former residence. | |||

{{start box}} | |||

{{succession box | | |||

before= [[George Goldwaite]] | | |||

title= U. S. Senator (Class 2) from Alabama | | |||

years=[[1877]]-[[1907]] | | |||

after= [[John H. Bankhead]] | |||

}} | |||

{{end box}} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* Fry, Joseph A., ''John Tyler Morgan and the Search for Southern Autonomy'', Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press | * Warner, Ezra J. (1959) ''Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders'', Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press ISBN 0807108235 | ||

* | * Fry, Joseph A.(1985) "John Tyler Morgan's Southern Expansionism," ''Diplomatic History'' | ||

* Fry, Joseph A. (1992) ''John Tyler Morgan and the Search for Southern Autonomy'', Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 0870497537. | |||

* Upchurch, Thomas Adams (April 2004) "Senator John Tyler Morgan and the Genesis of Jim Crow Ideology, 1889-1891." ''Alabama Review'' | |||

* Upchurch, Thomas Adams (May 28, 2014) "[http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1508 John Tyler Morgan]". Encyclopedia of Alabama - accessed February 22, 2016 | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* [http:// | * [http://www.archives.state.al.us/famous/j_morgan.html John Tyler Morgan] at the Alabama Hall of Fame | ||

* [http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=8760 John Tyler Morgan] at Findagrave.com | |||

* [http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CDOC-107sdoc11/pdf/GPO-CDOC-107sdoc11-2-89.pdf Carl Gutherz's 1893 portrait of Morgan] | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, John T.}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, John T.}} | ||

[[Category:1824 births]] | [[Category:1824 births]] | ||

[[Category:1907 deaths]] | [[Category:1907 deaths]] | ||

[[Category:Attorneys]] | |||

[[Category:U.S. Senators]] | [[Category:U.S. Senators]] | ||

[[Category:Confederate veterans]] | [[Category:Confederate veterans]] | ||

[[Category:Ku Klux Klan]] | [[Category:Ku Klux Klan]] | ||

[[Category:Alabama Hall of Fame]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:53, 22 February 2016

John Tyler Morgan (born June 20, 1824 in Athens, Tennessee; died June 11, 1907 in Washington D.C.) was a Confederate brigadier general, Klan leader and six-term U.S. Senator.

Morgan was the son of George Washington and Mary Frances Irby Morgan. He was educated at home by his mother until moving with the family to Calhoun County in 1833, where he began attending a local frontier school taught by Charles Samuel. He continued his education by reading law under his brother-in-law, Judge William Chilton, in Tuskegee. Upon his admission to the Alabama State Bar he opened a practice in Talladega. After a decade, he relocated to Selma, and also opened an office in the former capital of Cahaba. On February 11, 1846 he married Cornelia Willis of Talladega County. They had five children, two of whom died as infants and were buried at their mother's family's Thornhill plantation. Their son, John H., died in a boating accident in the Potomac in 1885. Their oldest daughter, Mary, served as her father's secretary and died in North Carolina in 1909. The other daughter, Cornelia, lived to 1944.

Morgan was active in local politics and earned a position as an aid to prominent secessionist William Yancey. He was an elector at the Southern Democrats' convention in Baltimore, Maryland that nominated John C. Breckenridge for president in 1860. He was also a delegate to the Alabama Secession Convention of January 1861.

During the Civil War Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, and was assigned to the 5th Alabama Infantry. He participated in the first Battle of Manassas and was later promoted to Major and then to Lieutenant Colonel under Robert E. Rhodes. He resigned from service in 1862, but quickly returned to the war, helping organize the 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers and serving as its Colonel at the Battle of Murfreesborough.

Morgan declined an offer to follow Rhodes into the Army of Northern Virginia and remained in the west, commanding troops at the Battle of Chickamauga. He was promoted to Brigadier General, commanding the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 9th and 51st Alabama Cavalry regiments during the Knoxville Campaign. His forces were routed by Union cavalry on January 27, 1864 and he was reassigned to the Atlanta Campaign, harassing federal troops under William T. Sherman during his "March to the Sea" across Georgia. Morgan spent the last days of the war attempting to organize former slaves into a home guard to oppose the depredations of occupation by Federal troops.

Following the end of the war, Morgan resumed his practice in Selma. After James Clanton was killed in a duel in Knoxville, Morgan succeeded him as Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. He also returned to politics, aiding the state Democratic party in its successful efforts to retake the state legislature from Reconstruction Republicans in 1875.

In 1876 Morgan again served as an elector for Democrat Samuel Tilden, who won the popular vote but narrowly lost to Rutherford Hayes in the electoral college. Morgan was also elected by the Alabama State Legislature to represent the state in the U.S. Senate. The state's senior senator, George Spencer, a native of New York elected by Alabama's Reconstruction legislature, moved to block his confirmation, but was unsuccessful. Morgan was re-elected in 1882, 1888, 1894 and 1906, serving from March 5, 1877 until his death.

At various times during his five terms as Senator, Morgan chaired the Senate Rules Committee, the Foreign Relations Committee, the Committee on Inter-oceanic Canals and the Committee on Public Health and National Quarantine. He was known as a highly-intelligent debater, and once joked that with enough preparation he could talk for three days for or against a bill, but, if unprepared, he could continue indefinitely.

Morgan was among the Senate's most vocal white supremacists, supporting the proliferation of "Jim Crow" laws to reinstitute political and economic impotence and social segregation for African-Americans. His filibuster of the Federal Elections Bill of 1890, along with his numerous published writings on the subject, was credited with turning the public against the idea of having federal troops stationed at polling places to enforce voting rights. He was involved in efforts to repeal the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and to resettle African-Americans outside the continental United States.

At the same time, Morgan was a leader for Democrats championing the Monroe Doctrine. He pushed for expanded global trade, hoping to boost Alabama's economy through the export of cotton, coal, iron and timber to new overseas markets. To that end he supported enlargement of the U.S. Navy and merchant marine, and the annexation of far-flung territories as spoils from the Spanish-American War. He championed a planned canal through Nicaragua to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. That canal ultimately was constructed through the isthmus of Panama. Morgan was also a vocal supporter of José Martí's efforts to liberate Cuba from Spanish rule, with the hope that it would become part of the United States.

Morgan also lobbied for reparations from the federal government to rebuild the campus of the University of Alabama, which had been burned by U.S. troops in April 1865.

President Harrison appointed him as an arbiter in a controversy over Bering Sea fisheries in 1892. In 1894 Morgan chaired the Senate investigation into the Hawaiian Revolution. He visited the Hawaiian islands in 1897 to support their annexation into the United States. President McKinley appointed him in July 1898 to the commission charged with establishing a territorial government in Hawaii.

In June 1907 Morgan died in Washington D.C. three months after being sworn in for his fifth term in the Senate. John H. Bankhead of Jasper was appointed to fill his remaining term. In the House of Representatives on April 25, 1908 Alabama congressman Tom Heflin remembered Morgan and his colleague, Edmund Pettus, as men who did more than than any others to "stay the hideous tide of negro domination," by reversing Reconstruction-era political reforms.

Morgan's body was transported to Selma for burial in that city's Live Oak Cemetery. Afterward the remains of his widow and son, who had predeceased him while they were living in Washington and had been buried in Rock Creek Cemetery there, were exhumed and re-interred alongside him in Selma. They were joined by the younger daughter Cornelia after her death in 1944.

Shortly after his death, the newly-completed Morgan Hall at the University of Alabama was named in Senator Morgan's honor. He was inducted into the Alabama Hall of Fame in 1953. Selma's John T. Morgan Academy, founded in 1965 as a "segregation academy," was named for the former Senator and held its first classes in his former residence.

| Preceded by: George Goldwaite |

U. S. Senator (Class 2) from Alabama 1877-1907 |

Succeeded by: John H. Bankhead |

References

- Warner, Ezra J. (1959) Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press ISBN 0807108235

- Fry, Joseph A.(1985) "John Tyler Morgan's Southern Expansionism," Diplomatic History

- Fry, Joseph A. (1992) John Tyler Morgan and the Search for Southern Autonomy, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 0870497537.

- Upchurch, Thomas Adams (April 2004) "Senator John Tyler Morgan and the Genesis of Jim Crow Ideology, 1889-1891." Alabama Review

- Upchurch, Thomas Adams (May 28, 2014) "John Tyler Morgan". Encyclopedia of Alabama - accessed February 22, 2016

External links

- John Tyler Morgan at the Alabama Hall of Fame

- John Tyler Morgan at Findagrave.com

- Carl Gutherz's 1893 portrait of Morgan