Wilson's Raid

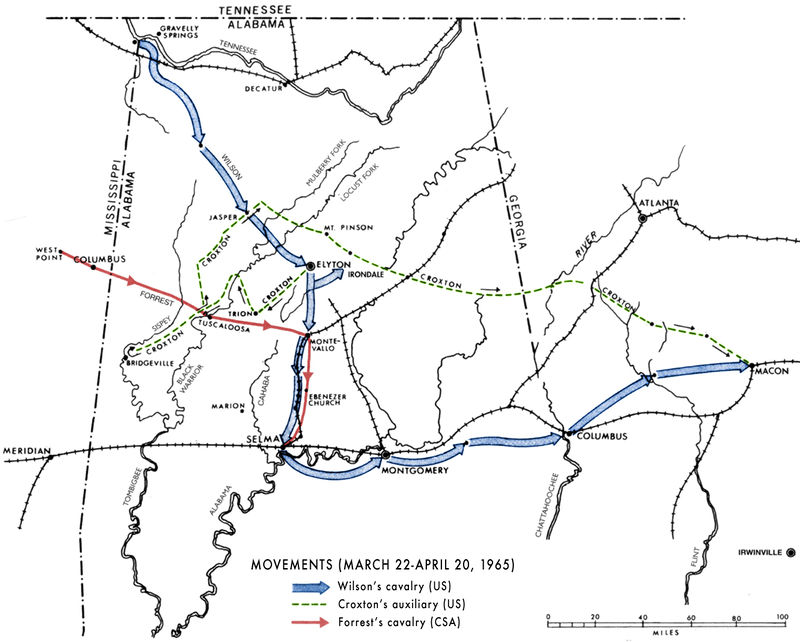

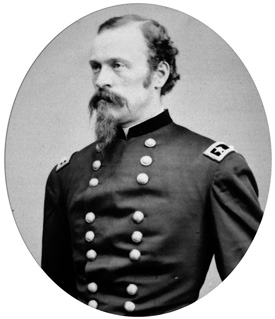

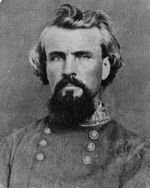

Wilson's Raid was a 28-day, 525-mile long cavalry operation through Alabama and Georgia in March-April 1865. It was the Civil War's largest cavalry raid, and final major engagement. Seeking to break Confederate supply lines and hasten the South's surrender, United States Brigadier General James H. Wilson led his Army Cavalry Corps to destroy Southern manufacturing facilities in Alabama and Georgia. His incursion was opposed unsuccessfully by a smaller Confederate force under Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest. The campaign was successful and curtailed the possibility that Confederate forces might regroup in the west, prolonging Civil War.

Background and opposing forces

By 1865, with the Union navy blockading seaports and the factories of Virginia and Tennessee destroyed or captured, the furnaces in the hills of Alabama were supplying as much as 70% of the iron used by the Confederate war effort. The large blast furnaces at Tannehill, Oxmoor, Irondale and Brierfield together produced as much as 75 tons per day, supplemented by many smaller bloomeries . The Ordnance and Naval Foundry in Selma, manned by a force of nearly 10,000 workers, was one of the last facilities producing cannon, large guns and ammunition.

After his victory at the Battle of Nashville, Union Major General George H. Thomas and his Army of the Cumberland found themselves with virtually no organized military opposition in the heart of the South. At the behest of General Ulysses Grant, Thomas ordered Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson (who commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Military Division of the Mississippi, but was attached to Thomas's army) to lead a raid to destroy the arsenal at Selma, by way of Tuscaloosa, in conjunction with Maj. Gen. Edward Canby's operations against Mobile.

Wilson led approximately 14,000 men in three divisions, commanded by Brig. Gens. Edward M. McCook, Eli Long, and Emory Upton. His corps camped near Gravelly Springs, just north of the Tennessee River in northwest Alabama through the first months of 1865. In addition to 12,000 mounted cavalry men, armed with 7-shot Spencer repeating carbines, Wilson had command of 1,500 foot soldiers with 36 batteries of 12-pound cannons, 58 pontoons for bridge-building, and 60 supply wagons.

With almost the entirety of the Confederate army engaged in North Carolina, Wilson's principal opponent was Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose Cavalry Corps of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana consisted of about 2,500 troopers organized into two small divisions, led by Brig. Gens. James R. Chalmers and William H. Jackson. The campaign also met resistance from two partial brigades under Brig. Gen. Philip D. Roddey and Colonel Edward Crossland, and a few militia acting as home guards.

Campaign

Wilson was delayed in crossing the rain-swollen Tennessee River, but got underway on March 22, 1865, departing Gravelly Springs, Alabama. He sent his forces in three separate columns to mask his intentions and confuse the enemy; Forrest learned very late in the raid that Selma was the primary target. Minor skirmishes occurred at Houston, Alabama on March 25 and the Black Warrior River on March 26, and Wilson's columns rejoined at Jasper on March 27, burning Jasper Methodist Church, the Walker County Courthouse and the Jasper Masonic Lodge before sweeping the countryside to commandeer provisions from farmsteads.

On March 28 the combined corps marched into Jones Valley. After a brief skirmish, the commanders settled into the stateliest homes in Elyton to question the locals and plan raids against the furnaces at Oxmoor and Irondale. As the cavalrymen camped along Red Mountain, one group of officers exchanged fire with a small unit of the home guard at the home of Sheriff Abner Killough at the spring in present-day Avondale Park. According to legend, Mrs Killough, who was home alone, suffered a non-fatal shot to the shoulder, shedding the only blood spilled by war in Jefferson County.

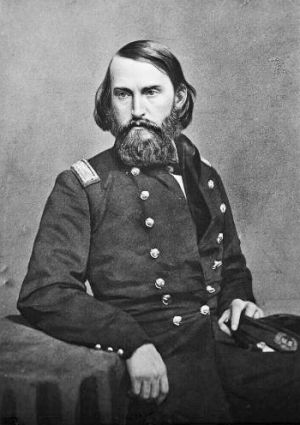

From Elyton, Wilson detached a brigade under Brig. Gen. John T. Croxton and sent them south and west to burn the Roupes Valley Ironworks at Tannehill, Brierfield Furnace and rolling mill in Bibb County, and the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, a training ground for militia and Confederate troops. Other detachments dismantled the Shelby Ironworks and C. B. Churchill's foundry in Columbiana. These movements diverted Chalmer's division away from Forrest's main force.

On March 31, Forrest was routed by the larger, better-armed Union force at Montevallo. The cavalrymen under Chalmers had not arrived to reinforce Forrest, but he could not wait. During the action, Forrest's headquarters were overrun and documents captured that gave valuable intelligence concerning his plans. Wilson dispatched McCook to link up with Croxton's brigade at Trion, and then led the remainder of his force rapidly toward Selma. Forrest made a stand on April 1 at Plantersville, near Ebenezer Church, and was routed once again. The Confederates raced toward Selma and deployed into a three-mile, semicircular defensive line anchored at both ends by the Alabama River.

Battle of Selma

The Battle of Selma occurred on April 2. The divisions of Long and Upton assaulted Forrest's hastily constructed works. The dismounted Union troopers broke through by afternoon, after brief periods of hand-to-hand combat; the militia troops abandoning their positions and fleeing were a primary reason for the entire line breaking. General Wilson personally led a mounted charge of the 4th U.S. Cavalry against an unfinished portion of the line. General Long was severely wounded in the head during the assault. Forrest, who was also wounded, and whose tiny corps was severely damaged, regrouped at Marion, where he finally rejoined with Chalmers. Wilson's men worked for over a week at destroying military facilities before departing for Montgomery, which they occupied on April 12.

Word reached the Union force of the surrender of Robert E. Lee on April 9 and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, but the raid continued, heading east into Georgia. The Battle of West Point, Georgia, occurred on April 16 when the brigade of Colonel Oscar H. La Grange attacked an earthwork defensive position named Fort Tyler. Although the Union men had to bridge a ditch under the fire of two 32-pounder guns inside the earthwork, Fort Tyler was captured. Confederate Brig. Gen. Robert C. Tyler, who had originally commanded the garrison at Selma before Forrest recommended that he evacuate the city, was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter, becoming the last general officer to be killed in the Civil War.

Also on April 16, Upton's division clashed with Confederate forces at Columbus, Georgia, capturing the city and its naval works and burning the "cottonclad" ramming ship, CSS Jackson. On April 20, Wilson's men captured Macon, and Wilson's Raid came to an end, only six days prior to General Joseph E. Johnston's surrender of all Confederate troops in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida to William Tecumseh Sherman in North Carolina.

Aftermath

Wilson's Raid had been a spectacular success. His men captured five fortified cities, 288 cannons, and 6,820 prisoners, at a cost of 725 Union casualties. Forrest's casualties, from a much smaller force, numbered 1,200. Wilson and his commander, George H. Thomas, did not tolerate uncontrolled behavior, such as looting, from their men. Residents accused Wilson's men of sacking Selma after the battle, but during house-to-house fighting, fires broke out, and renegades from both armies, along with escaping slaves, looted. Wilson quickly re-established discipline.

A sad postscript followed the raid. Union prisoners of war were released from Cahaba Prison near Selma by Wilson's Raid. Over 2,000 of these prisoners would be victims of one of the greatest disasters of the era, the explosion of the steamship Sultana on April 27, 1865.

References

- "Wilson's Raid." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 5 Jun 2006, 19:45 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 5 Jun 2006 [1].

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- National Park Service battle description for Selma

- Alabama state history

- Army of the Cumberland website on Wilson's Raid