Fred Shuttlesworth: Difference between revisions

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Shuttlesworth entered the Civil Rights fray by presenting petitions to the [[Birmingham City Commission]] asking them to hire black officers to the [[Birmingham Police Department]]. He was the main speaker at the January [[1956]] "Emancipation Rally" sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. | Shuttlesworth entered the Civil Rights fray by presenting petitions to the [[Birmingham City Commission]] asking them to hire black officers to the [[Birmingham Police Department]]. He was the main speaker at the January [[1956]] "Emancipation Rally" sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. | ||

On [[February 3]], [[1956]], Shuttlesworth accompanied [[Autherine Lucy]] and her attorney, [[Arthur Shores]] to enroll at the [[University of Alabama]]. At the time, Shuttlesworth was working as the membership chairman for the Alabama chapter of the NAACP. On [[May 26]] of that year, the NAACP was barred by state law from continuing to operate in Alabama, so Shuttlesworth led a group of ministers that founded the [[Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights]] to continue that work. The new group was launched at a mass meeting at [[Sardis Baptist Church]] on [[June 5]] with over 1,000 people in attendance. | |||

In December 1956 the United States Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation on buses in Montgomery was illegal. He announced that the ACMHR would test Birmingham's enforcement of similar segregation laws the day after Christmas. | In December 1956 the United States Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation on buses in Montgomery was illegal. He announced that the ACMHR would test Birmingham's enforcement of similar segregation laws the day after Christmas. | ||

===House bombed=== | ===House bombed=== | ||

On the night of December 25, his [[Fred Shuttlesworth residence|house]] was [[Shuttlesworth residence bombing (1956)|bombed]]. Though he was blown into the basement, he and his family and guests were unharmed. His miraculous survival affirmed his sense of duty to lead and earned a measure of awe from his followers. The next morning, he led a group of 300 demonstrators who boarded Birmingham busses. He filed a suit against the city after 22 of the demonstrators were arrested and fined. | On the night of [[December 25]], his [[Fred Shuttlesworth residence|house]] was [[Shuttlesworth residence bombing (1956)|bombed]]. Though he was blown into the basement, he and his family and guests were unharmed. His miraculous survival affirmed his sense of duty to lead and earned a measure of awe from his followers. The next morning, he led a group of 300 demonstrators who boarded Birmingham busses. He filed a suit against the city after 22 of the demonstrators were arrested and fined. | ||

===SCLC=== | ===SCLC=== | ||

On [[February 14]], [[1957]], Shuttlesworth joined [[Martin Luther King, Jr]], [[Ralph Abernathy]], and several other Southern religious leaders in forming the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on Transportation and Nonviolent Integration. He was installed as the secretary of the group, a position he held for 12 years. In March, Shuttlesworth and his wife [[Integration of Terminal Station (1957)|challenged]] the segregation of the [[Birmingham Terminal Station]] by using the waiting room reserved for whites. | |||

In May, Shuttlesworth expressed his vision of the spiritual movement for righteousness in a speech given to a gathering of black ministers in Washington D. C.: "We have arisen to walk with destiny, and we shall march till victory is won. Not a victory for Negroes, but a victory for America, for right, for righteousness. No man can make us hate; and no men can make us afraid. ... and let History, and they that come behind us, rejoice that we arose in strength, armed only with the weapon of Love..." | In May, Shuttlesworth expressed his vision of the spiritual movement for righteousness in a speech given to a gathering of black ministers in Washington D. C.: "We have arisen to walk with destiny, and we shall march till victory is won. Not a victory for Negroes, but a victory for America, for right, for righteousness. No man can make us hate; and no men can make us afraid. ... and let History, and they that come behind us, rejoice that we arose in strength, armed only with the weapon of Love..." | ||

===Beating=== | ===Beating=== | ||

That September, Shuttlesworth was badly beaten by a crowd while he attempted to enroll two of his daughters, Patricia and Ruby (nicknamed "Ricky"), at [[Phillips High School]]. | That September, Shuttlesworth was badly beaten by a crowd while he attempted to enroll two of his daughters, Patricia and Ruby (nicknamed "Ricky"), at [[Phillips High School]]. Recovering from the blows of bats and bicycle chains at [[University Hospital]], he pledged that attempts to integrate the schools would continue the very next day. | ||

===Court cases=== | ===Court cases=== | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Over the next few years the movement was active in petitioning for the removal of [[segregation laws]] and filing lawsuits to protect the civil rights of African American citizens. Funds to support these activities were raised at mass meetings, held weekly on Monday evenings in churches all across the city. The activities of the ACMHR were dogged by intimidation from the [[Ku Klux Klan]]. The Monday meetings were regularly attended by officers of the [[Birmingham Police Department]], who transcribed the speeches. Additional meetings were held during critical moments of action. Bombings increased in frequency at homes, churches and synagogues. | Over the next few years the movement was active in petitioning for the removal of [[segregation laws]] and filing lawsuits to protect the civil rights of African American citizens. Funds to support these activities were raised at mass meetings, held weekly on Monday evenings in churches all across the city. The activities of the ACMHR were dogged by intimidation from the [[Ku Klux Klan]]. The Monday meetings were regularly attended by officers of the [[Birmingham Police Department]], who transcribed the speeches. Additional meetings were held during critical moments of action. Bombings increased in frequency at homes, churches and synagogues. | ||

Shuttlesworth's national reputation was climbing, as well. In [[1958]] he began writing a weekly column for ''The Pittsburgh Courier'', a national black newspaper. | Shuttlesworth's national reputation was climbing, as well. In [[1958]] he began writing a weekly column for ''The Pittsburgh Courier'', a national black newspaper. He was sued by the ''New York Times'' for libel in [[1960]] and was ordered to pay $500,000 in damages. His private car was confiscated. The decision was reversed four years later by the United States Supreme Court. | ||

In [[1961]] Shuttlesworth helped to organize the Alabama leg of the [[Freedeom Rides]], initiated by the Chicago-based Congress for Racial Equality. A Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders was torched in [[Anniston]]. A violent mob met the arrival of a bus in Birmingham on May 14 and badly injured several activists. Commissioner of Public Safety [[Bull Connor]] indicated that police were not available to dispel the violence due to the Mother's Day holiday. | In [[1961]] Shuttlesworth helped to organize the Alabama leg of the [[Freedeom Rides]], initiated by the Chicago-based Congress for Racial Equality. A Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders was torched in [[Anniston]]. A violent mob met the arrival of a bus in Birmingham on [[May 14]] and badly injured several activists. Commissioner of Public Safety [[Bull Connor]] indicated that police were not available to dispel the violence due to the Mother's Day holiday. | ||

On [[August 1]], [[1961]] Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati to accept the pastorate of Revelation Baptist Church. Churches in several midwestern cities had competed for his services and the tripling of his salary allowed him to pay for his children to enroll in college. The safety of his family must also have been at issue as the movement was under siege by violent and well-connected racists. He chose Cincinnati in part because daily air service would allow him to continue leading the ACMHR in Birmingham and to guide the pursuance numerous federal lawsuits he initiated. | On [[August 1]], [[1961]] Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati to accept the pastorate of Revelation Baptist Church. Churches in several midwestern cities had competed for his services and the tripling of his salary allowed him to pay for his children to enroll in college. The safety of his family must also have been at issue as the movement was under siege by violent and well-connected racists. He chose Cincinnati in part because daily air service would allow him to continue leading the ACMHR in Birmingham and to guide the pursuance numerous federal lawsuits he initiated. | ||

In [[1962]] he accompanied King and other to a meeting with Vice President Lyndon Johnson and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, asking them to lead the way in ending racial segregation. The meeting was inconclusive. | |||

Shuttlesworth grew impatient with Reverend King leading up to the 1963 demonstrations. His letters to King after 1959 took a challenging tone, warning that "flowery speeches" were needed less than "the hard job of getting down and helping people." In the wake of Governor [[George Wallace]]'s inauguration pledge to preserve segregation in Alabama "forever"; and following King's failed Albany campaign where city leaders defused the protests by working with moderate Black leaders; the SCLC accepted Shuttlesworth's invitation to come to Birmingham to lead direct action which would force the city's hand. | Shuttlesworth grew impatient with Reverend King leading up to the 1963 demonstrations. His letters to King after 1959 took a challenging tone, warning that "flowery speeches" were needed less than "the hard job of getting down and helping people." In the wake of Governor [[George Wallace]]'s inauguration pledge to preserve segregation in Alabama "forever"; and following King's failed Albany campaign where city leaders defused the protests by working with moderate Black leaders; the SCLC accepted Shuttlesworth's invitation to come to Birmingham to lead direct action which would force the city's hand. | ||

Revision as of 11:10, 29 June 2008

Frederick Lee Shuttlesworth (born March 18, 1922 in Mugler, Montgomery County) was pastor of Bethel Baptist Church, a founder of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and a tireless leader of Birmingham's Civil Rights Movement. He is now retired and resides in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Shuttlesworth was born in the community of Mugler, in Montgomery County, one of nine children of Alberta Robinson, who later married William Nathan Shuttlesworth. He was raised on a farm in the Oxmoor community near Birmingham and attended Oxmoor Elementary School where he was taught by Israel Ramsey. He entered high school at Wenonah High School, but transferred to Rosedale High School before graduating in 1940.

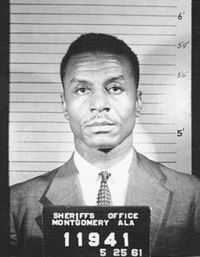

In 1941, Shuttlesworth, who was briefly jailed for operating a family still, married nurse Ruby Keeler. The couple moved to Mobile a year later, where he took a job as a truck driver and started studying to become a mechanic. His pastor there, E. A. Palmer, encouraged him to enter Bible college at the Cedar Grove Academy.

He delivered a sermon at Selma University, a Baptist theological school, in 1945 and decided to follow the call to preaching. He was ordanined in 1948 by Palmer and began preaching in Selma at the First (Colored) Baptist Church while he attended classes at Selma University. He graduated with an A.B. in 1951 and went on to get another A.B. in English from the Alabama State College in Montgomery, which he completed in 1953. Later that year he returned to Birmingham to accept the pastorate of Bethel Baptist Church, where he soon became a leader in the emerging campaign by African Americans to secure fundamental civil rights.

Civil Rights campaign

Shuttlesworth entered the Civil Rights fray by presenting petitions to the Birmingham City Commission asking them to hire black officers to the Birmingham Police Department. He was the main speaker at the January 1956 "Emancipation Rally" sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

On February 3, 1956, Shuttlesworth accompanied Autherine Lucy and her attorney, Arthur Shores to enroll at the University of Alabama. At the time, Shuttlesworth was working as the membership chairman for the Alabama chapter of the NAACP. On May 26 of that year, the NAACP was barred by state law from continuing to operate in Alabama, so Shuttlesworth led a group of ministers that founded the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights to continue that work. The new group was launched at a mass meeting at Sardis Baptist Church on June 5 with over 1,000 people in attendance.

In December 1956 the United States Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation on buses in Montgomery was illegal. He announced that the ACMHR would test Birmingham's enforcement of similar segregation laws the day after Christmas.

House bombed

On the night of December 25, his house was bombed. Though he was blown into the basement, he and his family and guests were unharmed. His miraculous survival affirmed his sense of duty to lead and earned a measure of awe from his followers. The next morning, he led a group of 300 demonstrators who boarded Birmingham busses. He filed a suit against the city after 22 of the demonstrators were arrested and fined.

SCLC

On February 14, 1957, Shuttlesworth joined Martin Luther King, Jr, Ralph Abernathy, and several other Southern religious leaders in forming the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on Transportation and Nonviolent Integration. He was installed as the secretary of the group, a position he held for 12 years. In March, Shuttlesworth and his wife challenged the segregation of the Birmingham Terminal Station by using the waiting room reserved for whites.

In May, Shuttlesworth expressed his vision of the spiritual movement for righteousness in a speech given to a gathering of black ministers in Washington D. C.: "We have arisen to walk with destiny, and we shall march till victory is won. Not a victory for Negroes, but a victory for America, for right, for righteousness. No man can make us hate; and no men can make us afraid. ... and let History, and they that come behind us, rejoice that we arose in strength, armed only with the weapon of Love..."

Beating

That September, Shuttlesworth was badly beaten by a crowd while he attempted to enroll two of his daughters, Patricia and Ruby (nicknamed "Ricky"), at Phillips High School. Recovering from the blows of bats and bicycle chains at University Hospital, he pledged that attempts to integrate the schools would continue the very next day.

Court cases

By 1965, Shuttlesworth was recognized as having brought more suits which reached the U. S. Supreme Court than any other person. He filed suits against the City of Birmingham and the State of Alabama for enforcing segregation laws and for passing and enforcing laws intended to silence him and his supporters. Most of his actions were supported by the NAACP's legal defense fund with help from local movement supporters.

Organization

Over the next few years the movement was active in petitioning for the removal of segregation laws and filing lawsuits to protect the civil rights of African American citizens. Funds to support these activities were raised at mass meetings, held weekly on Monday evenings in churches all across the city. The activities of the ACMHR were dogged by intimidation from the Ku Klux Klan. The Monday meetings were regularly attended by officers of the Birmingham Police Department, who transcribed the speeches. Additional meetings were held during critical moments of action. Bombings increased in frequency at homes, churches and synagogues.

Shuttlesworth's national reputation was climbing, as well. In 1958 he began writing a weekly column for The Pittsburgh Courier, a national black newspaper. He was sued by the New York Times for libel in 1960 and was ordered to pay $500,000 in damages. His private car was confiscated. The decision was reversed four years later by the United States Supreme Court.

In 1961 Shuttlesworth helped to organize the Alabama leg of the Freedeom Rides, initiated by the Chicago-based Congress for Racial Equality. A Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders was torched in Anniston. A violent mob met the arrival of a bus in Birmingham on May 14 and badly injured several activists. Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor indicated that police were not available to dispel the violence due to the Mother's Day holiday.

On August 1, 1961 Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati to accept the pastorate of Revelation Baptist Church. Churches in several midwestern cities had competed for his services and the tripling of his salary allowed him to pay for his children to enroll in college. The safety of his family must also have been at issue as the movement was under siege by violent and well-connected racists. He chose Cincinnati in part because daily air service would allow him to continue leading the ACMHR in Birmingham and to guide the pursuance numerous federal lawsuits he initiated.

In 1962 he accompanied King and other to a meeting with Vice President Lyndon Johnson and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, asking them to lead the way in ending racial segregation. The meeting was inconclusive.

Shuttlesworth grew impatient with Reverend King leading up to the 1963 demonstrations. His letters to King after 1959 took a challenging tone, warning that "flowery speeches" were needed less than "the hard job of getting down and helping people." In the wake of Governor George Wallace's inauguration pledge to preserve segregation in Alabama "forever"; and following King's failed Albany campaign where city leaders defused the protests by working with moderate Black leaders; the SCLC accepted Shuttlesworth's invitation to come to Birmingham to lead direct action which would force the city's hand.

Project C

Shuttlesworth termed the Spring 1963 demonstrations Project C for "confrontation". Knowing that if the conflict came to a head, the city -- and the nation -- would either have to side with integration, or with Bull Connor, the SCLC led a campaign of non-violent mass demonstrations.

Perceiving what was at stake, business and civic leaders had already put the wheels in motion to remove Connor and roll back the most oppressive segregation ordinances and practices. In fact, he had lost the mayoral election to moderate Albert Boutwell just days before. A group of ministers publicly expressed their sympathy for victims of injustice while pleading for patience and submission while they negotiated for a peaceful resolution. Their Call for Unity, published in The Birmingham News became the framework on which King, jailed on Connor's orders for violating the city's parade ordinance on April 12, 1963, constructed his eloquent and persuasive Letter from Birmingham Jail.

The demonstrations, which had started in earnest with sit-ins at downtown lunch counters, continued. Shuttlesworth led a march to Birmingham City Hall to petition for civil rights on April 6, but was blockaded by police who arrested the marchers after they knelt to pray. A state court issued an injunction specifically prohibiting the group from continuing to demonstrate. Connor vowed to jail as many people as broke the law. Members of the movement voted to continue in defiance of the law and not to stop until their demands were met. The game was set and Shuttlesworth joined King and Ralph Abernathy, clad in work clothes, on the April 12 march which led to King's incarceration. In the days following, hundreds of demonstrators were jailed. Shuttlesworth filed another suit against the city claiming that the parade permit was denied for unconstitutional reasons and that his arrest was, therefore, illegal. The United States Supreme Court found in his favor in 1969.

In early May, children joined the demonstrations. Teenage students were recruited to march, but younger children demanded to be able to participate. They, too, are herded off to jail. In early May, with the jails packed full, Connor ordered fire hoses and police dogs used to contain the demonstrators. While the movement still insisted on non-violent protest, the escalation in tactics touched both sides and threatened to break open. On May 8 firemen knocked Shuttlesworth off his feet in front of 16th Street Baptist Church, which was a rallying point for daily marches. He was hospitalized for a bruised rib.

Truce

In the meantime, the SCLC and City officials, with help from representatives of the U. S. Department of Justice, reached a truce. The ACMHR was not formally represented at the negotiations and Shuttlesworth vociferously demanded additional terms. A new settlement was reached two days later, which he outlined at a press conference in the courtyard of the A. G. Gaston Motel. While Shuttlesworth, still weak from his injury, adjourned from the event, even collapsing on the way out, King continued to speak of the great victory for democracy that was accomplished in Birmingham.

The following Saturday an outburst of bombings and arsons occurred, including a pair of blasts at the Gaston Motel. Leaders on both sides pleaded for peace, but tensions continued to rise during the summer leading up to the first year of integrated schooling in Birmingham. Shortly after school started, a bomb exploded at 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four girls and touching off a renewed crisis on the streets.

Shuttlesworth continued to play a leadership role demonstrations across the state, including the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965 that drew national support and ushered in the Civil Rights Act, a true victory for the movement.

Later life

Back home in Cincinnati, Shuttlesworth organized the Greater New Light Baptist Church in Cincinnati's North Avondale neighborhood in 1966 and continued to work actively for social and economic justice for African Americans. He has led protests of public utilities and the Cincinnati Police Department and even led protests in Washington against Reagan-era funding cuts for social services.

Shuttlesworth became a landlord in the 1970s, at one point owning more than 80 rental units. In 1988 he founded the Shuttlesworth Housing Foundation to assist low-income families with homeownership programs. A series of sexual harassment suits were filed against him, but none went to trial. He filed a countersuit alleging that another housing organization was fabricating the harassment claims, but a Federal Judge ruled in 1995 that there was no evidence of a conspiracy.

He served briefly in 2004 as the President of the SCLC, resigning in protest at the organization's "deceit, mistrust and ... lack of spiritual discipline and truth."

In August 2005 a benign brain tumor was removed. Shuttlesworth retired from the ministry in March 2006 a few days shy of his 84th birthday. In 2006 he married the former Sephira Bailey, 47 (he and his first wife, Ruby, seperated in 1969). He suffered a stroke on September 5, 2007. After spending a few months recovering at a nursing home, he returned to Birmingham for three weeks of therapy at the Lakeshore Rehabilitation Center. He accepted a "Live the Dream Award" from the city in February 2008. He was released from the hospital in April and moved into an apartment in the Watts Building downtown.

Shuttleworth's four children, Patricia, Ruby, Fred Jr, and Carolyn all went to college and became teachers. He has eleven grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Honors

In 1992 a statue of Shuttlesworth was placed directly in front of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which he helped to create. The Institute created the Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award in 2002, honoring him as the first recipient as well as the award's namesake.

F. L. Shuttlesworth Drive, renamed in 1988 is a four mile stretch of Huntsville Road from 27th Street North in Norwood to Erwin Dairy Road near Tarrant. There is also a North and South Fred Shuttlesworth Circle (the former North and South Crescent Avenues) in Cincinnati.

In 2001 President Clinton awarded Shuttlesworth the Presidential Citizens Medal. In 2008 Mayor Larry Langford proposed renaming the Birmingham International Airport the "Fred Shuttlesworth Birmingham International Airport" in his honor.

References

- Manis, Andrew M. (1999) "A Fire You Can't Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham's Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth." Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817309683

- White, Marjorie Longenecker (1998) A Walk to Freedom: The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society. ISBN 0943994241

- Branch, Taylor (1988) Parting The Waters; America In The King Years 1954-63. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671460978

- Manis, Andrew M. (Summer-Fall 2000) "Birmingham's Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth: unsung hero of the civil rights movement." Baptist History and Heritage. - accessed January 17, 2007

- Curnutte, Mark (January 20, 1997) "In the Name of Civil Rights: The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth carries on a 40-year fight as the movement's 'battlefield general'." Cincinnati Enquirer - accessed January 20, 2007.

- "The Champion" (November 26, 1965) Time Magazine.

- Walton, Val (February 19, 2008) "Rev. Shuttlesworth to return to Birmingham for post-stroke therapy." Birmingham News

- Garrison, Greg (June 29, 2008) "Legacy, history of civil rights icon Fred Shuttlesworth." Birmingham News