Charles Linn

Charles Linn (born Karl Erik Engelbert Sjödahl June 13, 1814 in Pohja, Finland; died August 7, 1882 in Birmingham) was a sailor, wholesaler, banker and industrialist.

Linn was the son of Erik Johan Sjödahl, chief inspector of the Billnäs Bruk ironworks, and his wife, the former Engla Gustava Collin. The family was of Swedish descent and lived near Pohja, on the southwestern coast of Finland, which was then a part of the Kingdom of Sweden and subject to the crown of Russia. Karl was enrolled at the Imperial Academy in Åbo (Turku), but the school was destroyed by fire in 1827. He was then apprenticed to a pharmacist in Jakobstad, but he left that position to stow away aboard a ship headed across the Atlantic.

When the crew discovered him, he was put to work as a cabin boy until he could be returned home. During the voyage he began to learn some English from the other sailors. In April 1830 he returned to the sea as part of the crew of a merchant ship. Over the next decade he made the Atlantic crossing many times. In a notation in his family bible he put the number of crossings at 53, and in a letter even claimed to have completed three full circuits of the globe, though these appear to be exaggerations. On June 13, 1833 he registered as an immigrant to the United States in New York City.

Sjödahl apprenticed as a maker of matches and pursued that trade in New York, Savannah, and New Orleans. There he accumulated enough capital to purchase a backpack of tinware, which he set off to peddle inland. He worked his way as far as Montgomery by 1838 and he resumed making and selling matches while sleeping on cotton bales at the riverside. After a while he partnered with Thomas Joseph in the fruit business. He continued to make matches to sell at their stand, even after it expanded with a bakery. To make it easier to do business, Sjödahl petitioned the state legislature to change his name to "Carl Linn", which was further Anglicized to "Charles".

Going back out on his own, Linn began transporting eggs and chickens to Mobile. From that beginning he opened his own mercantile house in 1840. His business grew and eventually brought him a significant income, despite a failed brickmaking venture. He purchased a large farm and made three voyages home to Finland. On his second trip he was married to his childhood sweetheart, the former Emelie Antoinette Forss, at Koskis on September 5, 1842. Linn brought her to Alabama as his wife. They had four children: Elvina Charlotte ("Ellen"), Charles W. (1846), Antoinette "Annie" Aurelia, and Edward. Emelie died in Montgomery on February 16, 1852 from complications related to Edward's birth.

Linn did not remain long without a helpmate. On December 28 of the same year he married the former Eliza Jane Summerlin of Montgomery. Over the next decade she bore him four more children: Mary Eliza, Lizzie Jane, George Thomas and George Marion, two of whom died in infancy. At the outbreak of the Civil War Linn sold his business interests and conducted his family to safety in Dresden, Germany. In a conversation with a fellow passenger on the way from Helsingfors (Helsinki) to Åbo, Linn expressed his opinions of the war:

Hearing me speak English, he immediately opened a conversation on the subject of the revolutionary movement in the United States. He did not know what we were fighting for; thought the North was acting very badly; regarded the people of the South as an oppressed and persecuted race; believed in slavery; considered the Lincoln government a perfect despotism, etc. In short, his views were a general epitome of the speeches, proclamations, and messages of the leading rebels throughout the South. I listened to him with great patience. He had an interesting family on board, all of whom spoke English; and what struck me as peculiar, a species of negro English common in the Southern States.

"Sir," said I, at length, "you surprise me! I had not expected to meet so strong an advocate of slavery and slave institutions in this latitude. Can it be possible that you are a Finn?"

"Yes, sir," he answered, "a genuine Finn—now on a visit to my native country after an absence of twenty-five years."

"Then you must have lived in the South?"

"Yes, sir; in Montgomery, Alabama. I have property there. It was getting pretty bad there for a family, and thought I had better pay a visit to Finland while the war was going on."

This accounted for the peculiar sentiments of my fellow-traveler! He seemed to be a very nice old gentleman, and I was sorry to find him tinctured with the heresies of rebellion. Farther conversation with him satisfied me that if he could get his property out of Montgomery, and put it in Massachusetts, he would be a very respectable Union man. I don’t think his heart was in the movement, though his pocket, doubtless, felt a considerable interest in it. (Brown-1867)

Linn's oldest son, Charles W. Linn, returned with him to Mobile, where they purchased a 193-foot long steam-driven sidewheel riverboat, the Kate Dale, and contracted with the Confederate Quartermaster Bureau as "blockade runners", transporting cotton and cattle hides to trade in Cuba for gold and badly-needed supplies. The expenses, risks and profits of these voyages were to be split between the owners and the government. In fact, the venture was successfully prevented by the Union blockade, and the Kate Dale was captured by the gunboat U.S.S. R. R. Cuyler on her maiden voyage near the Tortugas on July 14, 1863. Linn and his son were taken prisoner and sent to New York to stand trial as war criminals. They were both paroled, however, and after the end of the war the two Linns joined the wholesale grocery firm of Flash, Lewis & Co. in New Orleans, recruiting fellow Finns from the docks as workers. He made two more trans-Atlantic voyages in the late 1860s. He brought his family back to Montgomery in 1866, and later, in 1869, he brought 53 Finnish immigrants to Alabama, many of whom settled in the communities of Silverhill and Thorsby.

Linn sold his share in Flash, Lewis & Co., though Charles W. remained, and rejoined the rest of his family at their farm in Montgomery. Not long afterward James Powell and other investors in the Elyton Land Company interested him in the idea of opening a bank in the newly-founded City of Birmingham. He agreed and launched the National Bank of Birmingham in 1872 with $50,000 in gold. It was the first bank in the city, and the first in Northern Alabama chartered under the National Bank Act.

In 1873 Linn was elected to the Birmingham Board of Aldermen to serve in Mayor James Powell's administration. Later that year, Linn replaced his first bank building with the monumental 3-story National Bank of Birmingham building on the corner of 1st Avenue North and 20th Street at a time when the city's future was doubtful. The building became known as Linn's Folly, and it was there that Linn hosted the legendary New Year's Eve Calico Ball that signaled the city's emergence from a cholera epidemic and the nationwide financial panic.

In 1874 Linn created a small park, popularly called Linn's Park on the half-block behind the Relay House. George Marion Linn died in 1874, followed by his mother, Eliza Jane, on February 10, 1875. Linn married the former Fannie H. Clark on August 24 of the same year.

In 1875 Linn was elected to the board of managers for the Cooperative Experimental Coke & Iron Company, a venture proposed by Frank O'Brien to establish the commercial viability of iron made from local resources. That same year he purchased machine shop equipment from the former Confederate Iron Works in Selma and established the Birmingham Car & Foundry Company, which quickly expanded into the Linn Iron Works, operated by skilled workers brought in from Cleveland and Cincinnati.

On Saturday June 11, 1881 he hosted a celebration of his 67th birthday at Linn's Park with bands, ice cream, and speeches. The day was also marked by an eclipse of the moon. He died a little over a year later, in August 1882.

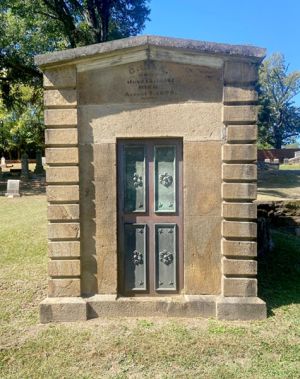

Before his death Linn issued a bold proclamation, which was later reproduced on a bronze plaque mounted on the side of his mausoleum at Oak Hill Cemetery:

I shall have my tomb built upon a high promontory above the town of Birmingham, in which you men profess to have so little faith, so that I may walk out on Judgment Day and view the greatest industrial city of the entire South.

The Linn Iron Works was absorbed along with the Alice Furnace Company into the Pratt Coal & Iron Company, which was later acquired by the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company, and eventually by U.S. Steel.

Downtown's Linn Park was re-named for Linn in the 1980s. The Linn-Henley Research Library is also named in honor of Linn and his descendants. A 1971 portrait painting of Linn by W. W. S. Wilson hangs in the stairwell. In 2005 Linn was inducted into the Birmingham Business Hall of Fame.

In 2013 a statue of Linn, sculpted by Branko Medenica, was installed at Linn Park by the Alabama-Mississippi Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The commission honored MS campaign chair Arthur Henley, a Linn descendant. During the 2020 George Floyd protests a group of vandals toppled the statue and damaged its base. As of May 2022 the statue had not re-erected.

References

- Brown, J. Ross (1867) The Land of Thor. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston, p. 239–240

- Dubose, John Witherspoon (1887) Jefferson County and Birmingham, Alabama: Historical and Biographical Birmingham: Teeple & Smith, Publishers; Caldwell Printing Works.

- Molton, Thomas Hunter (1922) Molton Family and Kinsmen. Birmingham: Birmingham Publishing Company

- Moyne, Ernest J. (April 1977) "Charles Linn: Finnish-Swedish Businessman, Banker, and Industrialist in Nineteenth-Century Alabama." The Swedish Pioneer Historical Quarterly. Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 97-105.

- Corley, Robert G. and Marvin Yeomans Whiting, editors (July 1979) Dedication. Journal of the Birmingham Historical Society. Vol. 6, No. 2

- Hall, Andy (August 24, 2014) "An Unlikely Blockade Runner, cont." Dead Confederates, A Civil War Era Blog

External links

- Charles Linn at Findagrave.com

- Charles Linnat Geni.com