Kelly Ingram Park: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Kelly Ingram Park''' is a four acre park located on [[Block 44]] in between [[16th Street North|16th]] and [[17th Street North|17th Street]]s and [[5th Avenue North|5th]] and [[6th Avenue North]] in the [[Birmingham]]'s [[Civil Rights District]]. The park, just outside the doors of the [[Sixteenth Street Baptist Church]], served as a central staging ground for large-scale demonstrations during the [[Civil Rights movement]] of the [[1960s]]. | |||

[[Image:Kelly Ingram Park 2010.jpg|center|thumb|800px|Kelly Ingram Park in 2010]] | |||

==History== | |||

[[Image:Kelly Ingram.jpg|left|thumb|85px|[[Kelly Ingram]]]] | |||

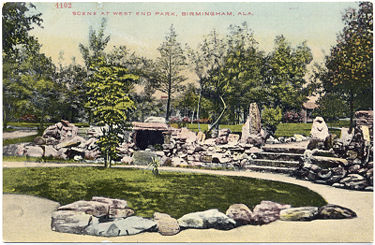

[[Image:West End Park postcard.jpg|right|thumb|375px|Postcard view of West End Park]] | [[Image:West End Park postcard.jpg|right|thumb|375px|Postcard view of West End Park]] | ||

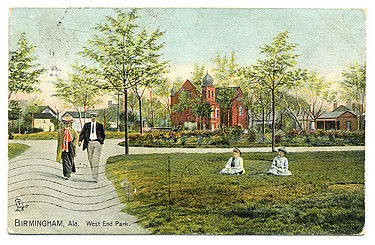

''' | [[Image:West End Park postcard 1906.jpg|right|thumb|375px|View of the park, with [[Temple Emanu-El]] in the background, c. 1906]] | ||

First known as '''West Park''', the block was set aside as a park by the [[Elyton Land Company]] as part of the original [[Plat of Birmingham]] created by [[William Barker]]. Along with two other park blocks ([[Linn Park]] (Central Park) and [[Marconi Park]] (East Park), it was sold to the City of Birmingham on [[February 21]], [[1883]] for a nominal price of $10. | |||

In the early days the park featured a stone grotto. [[16th Street Baptist Church]], [[Henley School]], and [[Temple Emanu-El]], at 1631 [[5th Avenue North]] were prominent landmarks surrounding the park at the turn of the century. West Park was sometimes called '''West End Park''', though there is some confusion with another park, an athletic field where [[7th Street North]] reached the railroad tracks west of [[Alice Furnace]], that was also commonly referred to as [[Slag Pile Field]]. | |||

West Park was renamed in [[1932]] for local firefighter [[Osmond Kelly Ingram]], who was the first sailor in the [[United States Navy]] to be killed in [[World War I]]. A [[Kelly Ingram monument|monument to Ingram]], consisting of a massive boulder with attached bronze plaques, was erected in the northwest corner of the park. | |||

==Civil Rights Movement== | ==Civil Rights Movement== | ||

{{Main|Birmingham Campaign}} | {{Main|Birmingham Campaign}} | ||

Reverends [[Martin Luther King | Reverends [[Martin Luther King Jr.]] and [[Fred Shuttlesworth]] directed the [[Birmingham Campaign|organized boycotts and protests]] of [[1963]] which centered on Kelly Ingram Park. It was here, during the first week of May [[1963]] that Birmingham police and firemen, under orders from Public Safety Commissioner [[Bull Connor]], confronted demonstrators, many of them children, first with mass arrests and then with [[police dogs and firehoses]]. Images from those confrontations, broadcast nationwide, spurred a public outcry which turned the nation's attention to the struggle for racial equality and helped insure the passage of [[Civil Rights laws]] and bring an end to public [[segregation]]. | ||

==Current park== | ==Current park== | ||

In [[ | In [[1990]], during the early stages of planning for the [[Birmingham Civil Rights Institute]], Mayor [[Richard Arrington]] attended a Mayors' Institute on City Design session hosted by Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he presented the project to professional planners. The group, led by Tulane Regional Urban Design Center director Grover Mouton, quickly identified the potential of using the open space of Kelly Ingram Park as a major component of a larger [[Civil Rights District]]. The concept evolved into redesigning the park as "A Place of Revolution and Reconciliation," and using art to enhance the interpretive program of the Institute. [[Grover Harrison Grover]] prepared the landscape design. | ||

Opened in [[1992]], the park is the setting for an ever-growing number of memorial sculptures related to the Civil Rights Movement. Besides a central fountain and a large commemorative statue of [[Martin Luther King, Jr]], there are three powerfully charged installations by artist [[James Drake]] which flank a circular "[[Freedom Walk]]" and bring the visitor inside the portrayals of terror and sorrow of the 1963 confrontations. [[Ronald McDowell]]'s "[[The Foot Soldier]]" is also located on the circular path on the south side of the park. Through the efforts of businessman [[A. G. Gaston]], monuments honoring public health worker [[Pauline Fletcher]] and educator [[Carrie Tuggle]] were installed in the park in [[1979]]. Additional markers honor [[Poro School of Beauty Culture]] founder [[Ruth Jackson]], attorney [[Arthur Shores]] and Pearl Harbor casualty [[Julius Ellsberry]]. | |||

A limestone [[Kneeling | A limestone [[Three Ministers Kneeling|sculpture by Raymond Kaskey]] depicts three ministers, [[John Thomas Porter]], [[Nelson Smith Jr]] and [[A. D. King]], kneeling in prayer. One corner of the park remembers other "unsung heroes"' of Birmingham's underrepresented. | ||

[[Image:Kelly Ingram Park birdseye.jpg|center|thumb|800px|Birds-eye view of Kelly Ingram Park in Spring, 1993 by HABS photographer Jet Lowe]] | |||

Currently the park hosts several local family festivals and cultural and entertainment events throughout the year. The Civil Rights Institute provides audio-tour guides for the park which feature remembrances by many of the figures directly involved in the confrontations. [[Urban Impact, Inc.]] also provides guided tours by appointment. | Currently the park hosts several local family festivals and cultural and entertainment events throughout the year. The Civil Rights Institute provides audio-tour guides for the park which feature remembrances by many of the figures directly involved in the confrontations. [[Urban Impact, Inc.]] also provides guided tours by appointment. | ||

In June [[2008]] two homeless men, Juan Perkins and Reginald Sanders, were arrested for "impersonating public servants" by trying to charge visitors for tours of the park. In November [[2009]] demonstrators with the "Tea Party Express II" caused controversy by selecting the park as the scene of their protests against the legitimacy of the Obama administration and against congressional plans to expand public healthcare coverage. | In June [[2008]] two homeless men, Juan Perkins and Reginald Sanders, were arrested for "impersonating public servants" by trying to charge visitors for tours of the park. In November [[2009]] demonstrators with the "Tea Party Express II" caused controversy by selecting the park as the scene of their protests against the legitimacy of the Obama administration and against congressional plans to expand public healthcare coverage. | ||

In [[2010]] BCRI board member [[Joel Rotenstreich]] led a drive to plant an [[Anne Frank tree]] in Kelly Ingram Park. Another group raised funds for a [[Four Spirits (memorial)|Four Spirits]] memorial to the girls killed in the [[1963 church bombing]]. That work, by [[Elizabeth MacQueen]], was dedicated on [[September 15]], [[2013]], the 50th anniversary of the tragedy. | |||

In part because of its role in the Civil Rights Movement, Kelly Ingram Park has been chosen as the site of many other public demonstrations and rallies, including the [[2015 Restoring Unity Rally]], the [[2017 Women's March]], and a major rally during the [[2020 George Floyd protests]]. On the evening after that [[May 31]], [[2020]] rally, a wave of "civil unrest" broke out at [[Linn Park]] and led to vandalism across [[downtown Birmingham]]. The city began enforcing a curfew and restrictions on public demonstrations, and temporarily erected fencing around the perimeter of both parks. The remnants of an art installation that incorporated nooses alarmed some passersby on [[June 15]], but investigators found no malicious intent. | |||

In September [[2023]] the park hosted the signing of a [[Wales-Birmingham International Friendship Pact]] by Mayor [[Randall Woodfin]] and Vaughan Gething, Minister of the Economy for the nation of Wales. Four trees were planted at the park in honor of the pact, and in memory of the four girls who died in the 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church. The ceremony was highlighted by a premier performance by [[Elias Hendricks III]] and [[Byron Thomas]] of a commemorative song by Welsh vocal arranger Christian Phillips. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* " | * "[http://cdm16044.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p4017coll2/id/32 3 parks 'given' to city are now worth $2 million]" (August 18, 1858) {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Gray, Jeremy (June 19, 2008) "Homeless men attempt to charge for Kelly Ingram Park tours." | * Moore, Geraldine (October 2, 1979) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4017coll2/id/1543 Monuments honoring black women unveiled in ceremony]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Gordon, Robert K. (November 9, 2009) "Tea Party Express makes stop in Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park." | * "[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kelly_Ingram_Park Kelly Ingram Park]" (March 29, 2006) Wikipedia - accessed March 29, 2006 | ||

* Gray, Jeremy (June 19, 2008) "Homeless men attempt to charge for Kelly Ingram Park tours." {{BN}} | |||

* Gordon, Robert K. (November 9, 2009) "Tea Party Express makes stop in Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park." {{BN}} | |||

* Gilchrist, William (June 18, 2014) remarks at "ULI’s 2002 Study on Downtown Birmingham – Then and Now". Urban Land Institute, Atlanta chapter. Terrific New Theater, Birmingham. panel discussion. | |||

* Robinson, Carol (June 15, 2020) "Sighting of noose in Kelly Ingram Park part of art exhibition, police say." {{BN}} | |||

* Bryant, Joseph D. (September 17, 2023) "Why Welsh students, leaders traveled 4,000 miles to Birmingham this week." {{AL}} | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

{{Locate address|address=Kelly+Ingram+Park}} | |||

* [http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/travel/civilrights/al10.htm National Park Service Page] | * [http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/travel/civilrights/al10.htm National Park Service Page] | ||

* [http://bcri.org/ Birmingham Civil Rights Institute] | * [http://bcri.org/ Birmingham Civil Rights Institute] | ||

* [http://www.heritagepreservation.org/PROGRAMS/SOS/4KIDS/arthist/policdog.htm Drake's sculptures] | * [http://www.heritagepreservation.org/PROGRAMS/SOS/4KIDS/arthist/policdog.htm Drake's sculptures] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Kelly Ingram Park|*]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:1871 establishments]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:1992 buildings]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Block 44]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:51, 22 October 2023

Kelly Ingram Park is a four acre park located on Block 44 in between 16th and 17th Streets and 5th and 6th Avenue North in the Birmingham's Civil Rights District. The park, just outside the doors of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, served as a central staging ground for large-scale demonstrations during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

History

First known as West Park, the block was set aside as a park by the Elyton Land Company as part of the original Plat of Birmingham created by William Barker. Along with two other park blocks (Linn Park (Central Park) and Marconi Park (East Park), it was sold to the City of Birmingham on February 21, 1883 for a nominal price of $10.

In the early days the park featured a stone grotto. 16th Street Baptist Church, Henley School, and Temple Emanu-El, at 1631 5th Avenue North were prominent landmarks surrounding the park at the turn of the century. West Park was sometimes called West End Park, though there is some confusion with another park, an athletic field where 7th Street North reached the railroad tracks west of Alice Furnace, that was also commonly referred to as Slag Pile Field.

West Park was renamed in 1932 for local firefighter Osmond Kelly Ingram, who was the first sailor in the United States Navy to be killed in World War I. A monument to Ingram, consisting of a massive boulder with attached bronze plaques, was erected in the northwest corner of the park.

Civil Rights Movement

Reverends Martin Luther King Jr. and Fred Shuttlesworth directed the organized boycotts and protests of 1963 which centered on Kelly Ingram Park. It was here, during the first week of May 1963 that Birmingham police and firemen, under orders from Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor, confronted demonstrators, many of them children, first with mass arrests and then with police dogs and firehoses. Images from those confrontations, broadcast nationwide, spurred a public outcry which turned the nation's attention to the struggle for racial equality and helped insure the passage of Civil Rights laws and bring an end to public segregation.

Current park

In 1990, during the early stages of planning for the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, Mayor Richard Arrington attended a Mayors' Institute on City Design session hosted by Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he presented the project to professional planners. The group, led by Tulane Regional Urban Design Center director Grover Mouton, quickly identified the potential of using the open space of Kelly Ingram Park as a major component of a larger Civil Rights District. The concept evolved into redesigning the park as "A Place of Revolution and Reconciliation," and using art to enhance the interpretive program of the Institute. Grover Harrison Grover prepared the landscape design.

Opened in 1992, the park is the setting for an ever-growing number of memorial sculptures related to the Civil Rights Movement. Besides a central fountain and a large commemorative statue of Martin Luther King, Jr, there are three powerfully charged installations by artist James Drake which flank a circular "Freedom Walk" and bring the visitor inside the portrayals of terror and sorrow of the 1963 confrontations. Ronald McDowell's "The Foot Soldier" is also located on the circular path on the south side of the park. Through the efforts of businessman A. G. Gaston, monuments honoring public health worker Pauline Fletcher and educator Carrie Tuggle were installed in the park in 1979. Additional markers honor Poro School of Beauty Culture founder Ruth Jackson, attorney Arthur Shores and Pearl Harbor casualty Julius Ellsberry.

A limestone sculpture by Raymond Kaskey depicts three ministers, John Thomas Porter, Nelson Smith Jr and A. D. King, kneeling in prayer. One corner of the park remembers other "unsung heroes"' of Birmingham's underrepresented.

Currently the park hosts several local family festivals and cultural and entertainment events throughout the year. The Civil Rights Institute provides audio-tour guides for the park which feature remembrances by many of the figures directly involved in the confrontations. Urban Impact, Inc. also provides guided tours by appointment.

In June 2008 two homeless men, Juan Perkins and Reginald Sanders, were arrested for "impersonating public servants" by trying to charge visitors for tours of the park. In November 2009 demonstrators with the "Tea Party Express II" caused controversy by selecting the park as the scene of their protests against the legitimacy of the Obama administration and against congressional plans to expand public healthcare coverage.

In 2010 BCRI board member Joel Rotenstreich led a drive to plant an Anne Frank tree in Kelly Ingram Park. Another group raised funds for a Four Spirits memorial to the girls killed in the 1963 church bombing. That work, by Elizabeth MacQueen, was dedicated on September 15, 2013, the 50th anniversary of the tragedy.

In part because of its role in the Civil Rights Movement, Kelly Ingram Park has been chosen as the site of many other public demonstrations and rallies, including the 2015 Restoring Unity Rally, the 2017 Women's March, and a major rally during the 2020 George Floyd protests. On the evening after that May 31, 2020 rally, a wave of "civil unrest" broke out at Linn Park and led to vandalism across downtown Birmingham. The city began enforcing a curfew and restrictions on public demonstrations, and temporarily erected fencing around the perimeter of both parks. The remnants of an art installation that incorporated nooses alarmed some passersby on June 15, but investigators found no malicious intent.

In September 2023 the park hosted the signing of a Wales-Birmingham International Friendship Pact by Mayor Randall Woodfin and Vaughan Gething, Minister of the Economy for the nation of Wales. Four trees were planted at the park in honor of the pact, and in memory of the four girls who died in the 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church. The ceremony was highlighted by a premier performance by Elias Hendricks III and Byron Thomas of a commemorative song by Welsh vocal arranger Christian Phillips.

References

- "3 parks 'given' to city are now worth $2 million" (August 18, 1858) Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Moore, Geraldine (October 2, 1979) "Monuments honoring black women unveiled in ceremony" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Kelly Ingram Park" (March 29, 2006) Wikipedia - accessed March 29, 2006

- Gray, Jeremy (June 19, 2008) "Homeless men attempt to charge for Kelly Ingram Park tours." The Birmingham News

- Gordon, Robert K. (November 9, 2009) "Tea Party Express makes stop in Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park." The Birmingham News

- Gilchrist, William (June 18, 2014) remarks at "ULI’s 2002 Study on Downtown Birmingham – Then and Now". Urban Land Institute, Atlanta chapter. Terrific New Theater, Birmingham. panel discussion.

- Robinson, Carol (June 15, 2020) "Sighting of noose in Kelly Ingram Park part of art exhibition, police say." The Birmingham News

- Bryant, Joseph D. (September 17, 2023) "Why Welsh students, leaders traveled 4,000 miles to Birmingham this week." AL.com