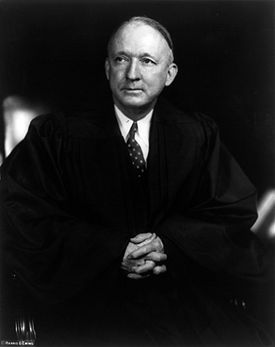

Hugo Black

- This article is about the U.S. Senator and Supreme Court Justice. For his son and grandson, both attorneys, see Hugo Black, Jr and Hugo Black III.

Hugo LaFayette Black (born February 27, 1886 in Wilcox County, died September 25, 1971 in Bethesda Naval Hospital) was an attorney, politician and jurist. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices in the 20th century, serving the fourth longest term, from 1937 to 1971. He also represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1926 to 1937, and worked previously as a lawyer and, briefly as a municipal judge for the Birmingham Police Department.

On the Supreme Court, Black is remembered for his literal reading of the Constitution and the position that the liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights were imposed on the states ("incorporated") by the 14th Amendment.

Early years

Hugo LaFayette Black was the youngest of the eight children born to William Lafayette Black and Martha Toland Black in a small wooden farmhouse in Harlan, an isolated town in Clay County.

Hugo decided at first to follow in the footsteps of his brother, Orlando, a physician. At age seventeen he left school in Ashland and enrolled in the 1902–03 term at Birmingham Medical School. Orlando later suggested that Hugo should enroll in law school. Black graduated the University of Alabama School of Law in June 1906, and moved back to Ashland to establish his legal practice. His office, located above a grocery store on the courthouse square, burned to the ground after 18 months of meager practice. Black then moved back to Birmingham in 1907 and staked out a specialty in labor law and personal injury cases.

Following his defense of an African American forced into a form of commercial slavery following incarceration, Black was befriended by A. O. Lane, then a judge who was connected with the case. When Lane was later elected to the Birmingham City Commission, he asked Black to serve as a police court judge, an experience that would be his only judicial experience prior to the Supreme Court. In 1912 Black resigned that seat in order to return to practicing law full-time. In 1914 he began a four-year term as the Jefferson County prosecutor.

Three years later, during World War I, Black resigned in order to join the Army. He enrolled in the Officers Training School at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, eventually reaching the rank of captain. He served in the 81st Field Artillery Unit near Chattanooga, Tennessee, but never participated in armed combat. In September 1918 shortly before the war ended, he returned to his practice in Birmingham.1

On February 23, 1921, he married Josephine Foster, with whom he would have three children: Hugo (born 1922), Sterling Foster (born 1924), and Martha Josephine (born 1933). The couple resided in the large home on Niazuma Avenue built by Josephine's father, the Presbyterian theologian Sterling Foster. As the Foster's fortunes declined, Black took over responsibility for the house, which he sold in the 1940s.

Josephine died after a long illness on December 6, 1951. Six years later, Black married Elizabeth Seay DeMeritte.

Black was a member of First Baptist Church of Birmingham.

Ku Klux Klan

In the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan re-emerged as a political force in defiance of waves of immigration to the United States. Some estimates put as many as 85,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama, wielding substantial influence over the state's elections.

On August 11, 1921, Black was asked to defend the Reverend Edwin Stephenson, a Klansman who had been accused of killing Father James Coyle, pastor of St Paul's Cathedral, on the steps of his rectory. In a trial where the presiding judge as well as several members of the jury were Klansmen. Black is reported to have approached prosecution witnesses with the question "You're a Catholic, aren't you?". The jury acquitted Stephenson.

Black became a member of the Robert E. Lee Klan No. 1 at a massive rally held at Edgewood Park in September 1923.2. Though he claimed to have attended only four meetings of the KKK, and to have quit the group in 1925. According to a published version of the Hugo Black Symposium, "Herman Beck, a leading Jewish merchant in Birmingham, encouraged his young friend Black to become a Klansman so that he could help contain the trouble-making element just coming to the fore of the organization in Alabama."3.

Former Grand Dragon James Esdale showed a handwritten note to Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Ray Sprigle dated July 9, 1925 and reading "Dear Sir Klansman, Beg to tender you herewith my resignation as a member of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, effective from this date on. Yours I.T.S.U.B. Hugo L. Black." ("I.T.S.U.B." stands for "In the Sacred, Unfailing Bond" in Klan lingo.)

Black is known, though, to have addressed the delegates to a statewide Klan "Klorero", as the Democratic nominee for U.S. Senate in September 1926 . A transcription of his remarks, also kept by Esdale, includes the statement, "I realize that I was elected by men who believe in the principles that I have sought to advocate and which are the principles of this organization."

Black did later publicly disavow the group.

Senate career

In 1926, Black sought election to the United States Senate from Alabama, following the retirement of Senator Oscar Underwood. He easily defeated his Republican opponent, E. H. Dryer, in the general election with 81% of the vote. He was reelected in 1932, winning 86% of the vote against Republican J. Theodore Johnson.4.

Senator Black gained a reputation as a tenacious and talented investigator. In 1934, for example, he chaired the committee that looked into the contracts awarded to air mail carriers under Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown, an inquiry which uncovered the Air Mail Scandal. In order to correct these abuses, he introduced the Black-McKellar Bill, later the Air Mail Act of 1934. The following year he participated in a Senate committee's investigation of lobbying practices. He publicly denounced the "highpowered, deceptive, telegram-fixing, letterframing, Washington-visiting" lobbyists, and advocated legislation requiring them to publicly register their names and salaries.5.

In 1935, Black became chairman of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor, a position he would hold for the remainder of his Senate career. In 1937 he sponsored the Black-Connery Bill, which sought to establish a national minimum wage and a maximum workweek of forty hours. Although the bill was initially rejected in the House of Representatives, a weakened version passed in 1938 (after Black left the Senate), becoming the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Black was an ardent supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. In particular, he was an outspoken advocate of the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937, popularly known as the court-packing bill, FDR's unpopular and unsuccessful plan to stack a hostile Supreme Court in his favor by adding more associate justices.

Supreme Court career

Soon after the failure of the court-packing plan, President Roosevelt obtained his first opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court Justice when conservative Willis Van Devanter retired. On August 12, 1937, Roosevelt nominated Black to fill the vacancy. By tradition, a senator nominated for an executive or judicial office was confirmed immediately and without debate. However, when Black was nominated, the Senate departed from this tradition for the first time since 1888; instead of confirming him immediately, it referred the nomination to the Judiciary Committee.

Republican Senator Warren Austin, objected to Black's nomination on constitutional grounds. Article I, Section 6 of the Constitution provides that "No Senator or Representative shall, during the Time for which he was elected, be appointed to any civil Office under the Authority of the United States which shall have been created, or the emoluments whereof shall have been increased during such time." Austin argued that since retirement benefits for Supreme Court Justices over 70 had recently been increased, Black was constitutionally barred from taking the post. Black's defenders responded that he was then 51 and would not receive the increased pension until he turned seventy — long after his senatorial term would have expired. Ultimately, Austin's objections were set aside, and the Judiciary Committee recommended Black's confirmation by a vote of 13–4 on August 16 of that year.6.

The next day the full Senate considered Black's nomination. Rumors relating to Black's Klan involvement the surfaced, and Democratic Senators Royal S. Copeland and Edward R. Burke urged their colleagues to defeat the nomination. However, with no conclusive evidence of Black's involvement available at the time, the Senate voted 63-13 to confirm Black's nomination after six hours of debate.7. He resigned from the Senate and was sworn in as an Associate Justice three days later. Alabama Governor Bibb Graves appointed his wife, Dixie, to fill Black's vacated Senate seat.

The next month, Ray Sprigle, a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published an in-depth exposé of Black's KKK past in a series of Pulitzer Prize-winning articles. Facing an inflamed public, Black delivered a nationally broadcast radio address in which he explained his decision to join and subsequently resign from the KKK.8. The controversy, kept alive in the press, only subsided after Black contributed to a ruling in favor of a group of African American defendents in the 1940 Chambers v. Florida case.

During his early years on the Supreme Court, Black helped reverse several earlier court decisions taking a narrow interpretation of federal power. Many New Deal laws that would have been struck down under earlier precedents were thus upheld. In 1939 Black was joined on the Supreme Court by fellow Roosevelt appointees Felix Frankfurter and William O. Douglas. Douglas voted alongside Black in several cases, especially those involving the First Amendment, while Frankfurter soon became one of Black's ideological foes.

Justice Black became involved in a bitter dispute with Justice Robert H. Jackson as a result of Jewell Ridge Coal Corp. v. Local 6167, United Mine Workers (1945). In this case the Court ruled 5–4 in favor of the union; Black voted with the majority, while Jackson dissented. However, the coal company requested the Court rehear the case on the grounds that Justice Black should have recused himself, as the mine workers were represented by Black's former law partner. Under the Supreme Court's rules, each Justice was entitled to determine the propriety of disqualifying himself. A statement accompanying the court's denial of rehearing, penned by Jackson and signed by Frankfurter, affirmed the Court's rules without endorsing Black's participation in the judgment.

During the ensuing decades, marked by Cold War fervor, the Supreme Court considered, and upheld, the validity of numerous anti-communist laws. For example, in American Communications Association v. Douds (1950), the Court upheld a law that required labor union officials to forswear membership in the Communist Party. Black dissented, claiming that the law violated the First Amendment's free speech clause. Similarly, in Dennis v. United States (1951), the Court upheld the Smith Act, which made it a crime to "advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States." The law was often used to prosecute individuals for joining the Communist Party. Black again dissented, writing:

"Public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the conviction of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that, in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society."

Beginning in the late 1940s, Black wrote for the Court in several cases relating to the establishment clause, where it had historically insisted on the strict separation of church and state. The most notable of these was Engel v. Vitale (1962), which declared state-sanctioned prayer in public schools unconstitutional. This provoked considerable opposition, especially in the South.

In 1953 Chief Justice Vinson died and was replaced by Earl Warren. Black was often regarded as a member of the liberal wing of the Court, together with Warren, Douglas, William Brennan, and Arthur Goldberg. Yet while he often voted with them on the Warren Court, he occasionally took his own line, most notably Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which established that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. Black's most prominent ideological opponent on the Warren Court was John Marshall Harlan II, who replaced Justice Jackson in 1955. Black and Harlan disagreed on several issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the scope of the due process clause, and the "one man, one vote" principle.

Jurisprudence

Because of Black's his insistence on a strict textual analysis of Constitutional issues, as opposed to the process-oriented jurisprudence of many of his colleagues, it is difficult to characterize Black as a liberal or a conservative as those terms are generally understood in the current political discourse United States. On the one hand, his literal reading of the Bill of Rights and his theory of incorporation often translated into support for strengthening civil rights and civil liberties. On the other hand, Black consistently opposed the doctrine of substantive due process and believed that there was no constitutionally-protected right to privacy.

Black was noted for his advocacy of a textualist approach to constitutional interpretation. He took a "literal" or absolutist reading of the provisions of the Bill of Rights and believed that the text of the Constitution is absolutely determinative on any question calling for judicial interpretation, leading to his reputation as a "strict constructionist".

Thus, Black refused to join in the efforts of the justices on the Court who sought to abolish capital punishment, efforts that succeeded (temporarily) in the term immediately following Black's death. He claimed that the Fifth and 14th Amendments' references to taking of "life" meant that approval of the death penalty was implicit in the Bill of Rights. He also was not persuaded that a right of privacy was implicit in the 9th or 14th amendments, and dissented from the Court's 1965 Griswold decision which invalidated criminal convictions for the sale of contraceptives.

In his dissent, Black wrote:

The idea is that the Constitution must be changed from time to time, and that this Court is charged with a duty to make those changes. For myself, I must, with all deference, reject that philosophy. The Constitution makers knew the need for change, and provided for it. Amendments suggested by the people's elected representatives can be submitted to the people or their selected agents for ratification. That method of change was good for our Fathers, and, being somewhat old-fashioned, I must add it is good enough for me.

Federalism

Like the other Justices appointed by President Roosevelt, Black held an expansive view of federal power, especially under the commerce clause. Previously, during the 1920s and 1930s, the Court had interpreted this clause narrowly, often striking down laws on the grounds that Congress had overstepped its authority. After 1937, however, the Supreme Court overturned several precedents and affirmed a broader interpretation of the commerce clause. Black consistently voted with the majority in these decisions; for example, he joined United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941), Wickard v. Filburn (1942), Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States (1964), and Katzenbach v. McClung (1964).

In several other federalism cases, however, Black ruled against the federal government. For instance, he partially dissented from South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966), in which the Court upheld the validity of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In an attempt to protect the voting rights of African Americans, the act required any state whose population was at least 5% African American to obtain federal approval before changing its voting laws. Black wrote that the law, "... by providing that some of the States cannot pass state laws or adopt state constitutional amendments without first being compelled to beg federal authorities to approve their policies, so distorts our constitutional structure of government as to render any distinction drawn in the Constitution between state and federal power almost meaningless." 9. Similarly, in Oregon v. Mitchell (1970), he delivered the opinion of the court holding that the federal government was not entitled to set the voting age for state elections.

In the law of federal jurisdiction, Black made a large contribution by authoring the majority opinion in Younger v. Harris. This case, decided during Black's last year on the Court, has given rise to what is now known as Younger abstention. According to this doctrine, an important principle of federalism called "comity"—that is, respect by federal courts for state courts—dictates that federal courts abstain from intervening in ongoing state proceedings, absent the most compelling circumstances. The case is also famous for its discussion of what Black calls "Our Federalism," a discussion in which Black insists on "proper respect for state functions, a recognition of the fact that the entire country is made up of a Union of separate state governments, and a continuance of the belief that the National Government will fare best if the States and their institutions are left free to perform their separate functions in their separate ways." 10.

Civil Rights

During his tenure on the bench, Black established a record sympathetic to the civil rights movement. He joined the majority in Shelley v. Kramer (1948), which invalidated the judicial enforcement of racially restrictive covenants. Similarly, he was part of the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education (1954) Court that struck down racial segregation in public schools. For this, he was burnt in effigy by segregationists back in Alabama.

Black also wrote the court's majority opinion in Korematsu v. United States, which validated Roosevelt's decision to inter Japanese Americans on the West Coast during World War II, a decision roundly criticized today. He stated that, while race-based internment was "constitutionally suspect", it was permissible during "circumstances of direst emergency and peril." In dissent Justice Frank Murphy accused the government of "fall[ing] into the ugly abyss of racism."

1st Amendment

Black took an absolutist approach to 1st Amendment jurisprudence, as reflected by his famous aphorism, "No law means no law." As a result he often found himself in dissent, although he was usually joined by Justice William O. Douglas. However, his interpretation of the establishment clause was (for the most part) shared by his colleagues, especially during the tenure of Chief Justice Warren.

Black took a dim view of government entanglement with religion. He believed that the First Amendment erected a "wall of separation" between church and state. During his career Black wrote several important opinions relating to church-state separation. He delivered the opinion of the court in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), which held that the establishment clause was applicable not only to the federal government, but also to the states. His majority opinion in McCollum v. Board of Education (1948) held that the government could not provide religious instruction in public schools. In Torasco v. Watkins (1961), he delivered an opinion which affirmed that the states could not use religious tests as qualifications for public office. Similarly, he authored the majority opinion in Engel v. Vitale (1962), which declared it unconstitutional for states to require the recitation of official prayers in public schools.

Justice Black is often regarded as a leading defender of 1st Amendment rights such as the freedom of speech and of the press. He refused to accept the doctrine that the freedom of speech could be curtailed on national security grounds. Thus, in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), he voted to allow newspapers to publish the Pentagon Papers despite the Nixon Administration's contention that publication would have security implications. In his concurring opinion, Black stated, "The word 'security' is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment." 11. He rejected the idea that the government was entitled to punish "obscene" speech. Likewise, he argued that defamation laws abridged the freedom of speech and were therefore unconstitutional. Most members of the Supreme Court rejected both of these views. However, Black's interpretation did attract the support of Justice Douglas.

However he did not believe that individuals had the right to speak wherever they pleased. He delivered the majority opinion in Adderley v. Florida (1966), controversially upholding a trespassing conviction for protestors who demonstrated on government property. He also dissented from Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), in which the Supreme Court ruled that students had the right to wear armbands (as a form of protest) in schools, writing, "While I have always believed that under the 1st and 14th Amendments neither the State nor the Federal Government has any authority to regulate or censor the content of speech, I have never believed that any person has a right to give speeches or engage in demonstrations where he pleases and when he pleases." 12.

Moreover, Black took a narrow view of what constituted "speech" under the 1st Amendment. For example, he did not believe that flag burning was protected speech; in Street v. New York (1969), he wrote: "It passes my belief that anything in the Federal Constitution bars a State from making the deliberate burning of the American flag an offense." 13. Similarly, he dissented from Cohen v. California (1971), in which the Court held that wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" was speech protected by the 1st Amendment. He agreed that this activity "was mainly conduct, and little speech."

Criminal procedure

Black adopted a narrower interpretation of the 4th Amendment than many of his colleagues on the Warren Court. He dissented from Katz v. United States (1967), in which the Court held that warrantless wiretapping violated the Fourth Amendment's guarantee against unreasonable search and seizure. He argued that the 4th Amendment only protected tangible items from physical searches or seizures. Thus, he concluded that telephone conversations were not within the scope of the amendment, and that warrantless wiretapping was consequently permissible.

Justice Black originally believed that the Constitution did not require the exclusion of illegally seized evidence at trials. In his concurrence to Wolf v. Colorado (1949), he claimed that the exclusionary rule was "not a command of the 4th Amendment but ... a judicially created rule of evidence." 14. But he later changed his mind and joined the majority in Mapp v. Ohio (1961), which applied it to state as well as federal criminal investigations. In his concurrence, he indicated that his support was based on the 5th Amendment's guarantee of the right against self-incrimination, not on the 4th Amendment's guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures. He wrote, "I am still not persuaded that the Fourth Amendment, standing alone, would be enough to bar the introduction into evidence ... seized ... in violation of its commands." 15.

In other instances Black took a fairly broad view of the rights of criminal defendants. He joined the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), which required law enforcement officers to warn suspects of their rights prior to interrogations, and consistently voted to apply the guarantees of the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 8th Amendments at the state level.

Incorporation

One of the most notable aspects of Justice Black's jurisprudence was the view that the entirety of the federal Bill of Rights was applicable to the states. Originally, the Bill of Rights was binding only upon the federal government, as the Supreme Court ruled in Barron v. Baltimore (1833). According to Black the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, "incorporated" the Bill of Rights, or made it binding upon the states as well. In particular, he pointed to the Privileges or Immunities Clause, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States." He proposed that the term "privileges or immunities" encompassed the rights mentioned in the first eight amendments to the Constitution.

Black first expounded this theory of incorporation when the Supreme Court ruled in Adamson v. California (1947) that the 5th Amendment's guarantee against self-incrimination did not apply to the states. In an appendix to his dissenting opinion, Justice Black analyzed statements made by those who framed the 14th Amendment, reaching the conclusion that "the 14th Amendment, and particularly its privileges and immunities clause, was a plain application of the Bill of Rights to the states." 16.

This theory sparked an extended debate within the Court and the academic legal community. It attracted the support of Justices such as Frank Murphy and William O. Douglas. However, it never achieved the support of a majority of the Court. The most prominent opponents of Black's theory were Justices Frankfurter and Harlan, who argued that the 14th Amendment did not incorporate the Bill of Rights per se, but merely protected rights that are "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty."

The Supreme Court never accepted the argument that the 14th Amendment incorporated the entirety of the Bill of Rights. However, it did agree that some "fundamental" guarantees were made applicable to the states. For the most part, during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, only 1st Amendment rights were deemed sufficiently fundamental by the Supreme Court to be so incorporated.

However, during the 1960s the Court under Chief Justice Warren took the process much further, making almost all guarantees of the Bill of Rights binding upon the states. Thus, although the Court failed to accept Black's theory of total incorporation, the end result of its jurisprudence is very close to what Black advocated.

Due process clause

Justice Black was well-known for his rejection of the doctrine of substantive due process. Most Supreme Court Justices accepted the view that the due process clause encompassed not only procedural guarantees, but also "fundamental fairness" and fundamental rights. Thus, it was argued that due process included a "procedural" component as well as a "substantive component."

Black advocated a much narrower interpretation of the clause. In his dissent to In Re Winship, he analyzed the history of the term "due process of law", and concluded: "For me, the only correct meaning of that phrase is that our Government must proceed according to the 'law of the land'—that is, according to written constitutional and statutory provisions as interpreted by court decisions." 17.

None of Black's colleagues shared this interpretation of the due process clause. Harlan in particular was highly critical of it, indicating his "continued bafflement at my Brother Black's insistence that due process ... does not embody a concept of fundamental fairness" in his Winship concurrence. 18. Since Black's death the Court has continued to apply the doctrine of substantive due process (most notably in Roe v. Wade, which proclaimed that abortion was a constitutionally protected right).

Voting rights

Black was one of the Supreme Court's foremost defenders of the "one man, one vote" principle. He delivered the opinion of the court in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964), holding that the Constitution required congressional districts in any state to be approximately equal in population. He concluded that the Constitution's command "that Representatives be chosen 'by the People of the several States' means that as nearly as is practicable one man's vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another's." 19. Likewise, he voted in favor of Reynolds v. Sims (1965), which extended the same requirement to state legislative districts on the basis of the equal protection clause.

At the same time, Black did not believe that the equal protection clause made poll taxes unconstitutional. Thus, he dissented from the Court's ruling in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966) invalidating the use of the poll tax as a qualification to vote. He criticized the Court for exceeding its "limited power to interpret the original meaning of the Equal Protection Clause" and for "giving that clause a new meaning which it believes represents a better governmental policy." 20.

Resignation and death

Justice Black admitted himself to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, on August 28, 1971, and subsequently resigned from the Court on September 17. He suffered a stroke two days later and died on September 25. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Black had served on the Supreme Court for 34 years, making him the fourth longest-serving Justice in Supreme Court history.

President Richard Nixon first considered nominating Hershel Friday to fill the vacant seat, but changed his mind after the American Bar Association found Friday unqualified. Nixon then nominated Lewis Powell, who was confirmed by the Senate.

In 1986 Black appeared on a postage stamp issued by the United States Postal Service. He is one of only three Associate Justices so honored; the other two are Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr and Thurgood Marshall. 24. In 1987, Congress passed a law designating the new courthouse building for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama in Birmingham, as the "Hugo L. Black United States Court House".

| Preceded by: Oscar Underwood |

U.S. Senator from Alabama March 4, 1927–August 19, 1937 |

Succeeded by: Dixie Graves |

| Preceded by: Willis Van Devanter |

Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court August 19, 1937–September 17, 1971 |

Succeeded by: Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr |

References

- Federal Judicial Center. "Black, Hugo Lafayette"

- Van Der Veer, Virginia. "Hugo Black and the KKK."

- Van Der Veer, Virginia. (1978). Hugo Black and the Bill of Rights: Proceedings of the First Hugo Black Symposium in American History on 'The Bill of Rights and American Democracy.' Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Carr, Adam. "Direct Elections to the United States Senate 1914-98.

- United States Senate. "Lobbyists."

- Van Der Veer - 1978

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Rehnquist, William H. (1987) The Supreme Court. New York:Knopf

- Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951). (Black, J., dissenting).

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). (Black, J., dissenting).

- South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966). (Black, J., concurring and dissenting).

- Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971).</ref>

- New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971). (Black, J., concurring).

- Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969). (Black, J., dissenting).

- Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576 (1969). (Black, J., dissenting).

- Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949). (Black, J., concurring).

- Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). (Black, J., concurring).

- Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 (1947). (Black, J., dissenting

- In Re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970). (Black, J., dissenting).

- In Re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970). (Harlan, J., concurring).

- Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964).

- Harper v. Virginia Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966). (Black, J., dissenting).

- United States Postal Service. Philatelic News.

Additional reading

- Van der Veeer (April 1968) "Hugo Black and the K.K.K." American Heritage, Vol. 19, No. 3

- Ball, Howard. (1992). Of Power and Right : Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and America's Constitutional Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ball, Howard. (1996). Hugo L. Black: Cold Steel Warrior. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Black, Hugo, Jr. (1975). My Father: A Remembrance. New York: Random House.

- Dunne, Gerald T. (1977). Hugo Black and the Judicial Revolution. New York: Simon Schuster.

- Frank, John Paul. (1949). Mr. Justice Black, the Man and His Opinions. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Freyer, Tony Allen. (1990). Hugo L. Black and the Dilemma of American Liberalism. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

- Mr. Justice and Mrs. Black: The Memoirs of Hugo L. Black and Elizabeth Black. (1986). New York: Random House.

- Simon, James F. (1989). The Antagonists: Hugo Black, Felix Frankfurter, and Civil Liberties in America. New York: Simon & Schuster

- Newman, Roger K. (1997) Hugo Black: A Biography. New York: Fordham University Press ISBN 0823217868

- Suitts, Steve. (2005). Hugo Black of Alabama. Montgomery, AL: New South Books.

- Yarbrough, Tinsley E. (1989). Mr. Justice Black and His Critics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.