Alabama Theatre: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:Alabama_Theater_in_2018.jpg|800px|center]] | ||

'''The Alabama Theatre''', is a 2, | '''The Alabama Theatre''', is a 2,000 seat "movie palace" opened by Paramount Studios in [[1927]] at 1817 [[3rd Avenue North]], and a major landmark in downtown [[Birmingham]]'s "[[Theater District]]". | ||

Paramount constructed the theater as its first-run showplace, overtaking the [[Strand Theater|Strand]] and [[Galax Theater|Galax]] in that role. It was constructed to showcase the silent films of the era, with staging for live performances which Publix produced to accompany feature screenings at its largest theaters. A feature of the house is | Paramount constructed the theater as its first-run showplace, overtaking the [[Strand Theater|Strand]] and [[Galax Theater|Galax]] in that role. It was constructed to showcase the silent films of the era, with staging for live performances which Publix produced to accompany feature screenings at its largest theaters. A feature of the house is its "[[Mighty Wurlitzer]]" theater organ, the console of which can be raised to stage level for recitals or lowered out of sight to accompany films. | ||

Now painstakingly restored, the Alabama is operated by [[Birmingham Landmarks]], a non-profit corporation founded by [[Cecil Whitmire]]. The Alabama hosts numerous live concerts and classic movie screenings, as well as weddings and private events throughout the year. | Now painstakingly restored, the Alabama is operated by [[Birmingham Landmarks]], a non-profit corporation founded by [[Cecil Whitmire]] in [[1987]]. The Alabama Theatre hosts numerous live concerts and classic movie screenings, as well as recitals, weddings and private events throughout the year. | ||

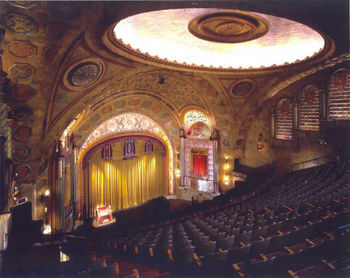

[[Image:Alabama_Theatre_interior.jpg|right|thumb|350px|Interior of the Alabama Theatre after its recent resotration. Photograph by [[M. Lewis Kennedy]].]] | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

[[Image:Alabama Theatre construction.jpg|left|thumb|375px|View of framing (1927) by [[A. C. Keily]]]] | [[Image:Alabama Theatre construction.jpg|left|thumb|375px|View of framing (1927) by [[A. C. Keily]]]] | ||

The Alabama was built by Paramount Studio's Publix Theater division as an opulent "movie palace" for screening silent films. It is one of two extant theaters, along with Knoxville's Tennessee Theatre (1928), known to have been designed by the Chicago architecture firm of Graven and Mayger. Arthur G. Larson was the architect responsible for the design.<!--a June 24, 1927 ad for Brunswick-Kroeschell Refrigeration air conditioning equipment lists "C. W. & Geo. L. Rapp" as the architects ([http://ia601205.us.archive.org/BookReader/BookReaderImages.php?zip=/20/items/motion35moti/motion35moti_jp2.zip&file=motion35moti_jp2/motion35moti_1404.jp2 link])--> Construction plans for the Alabama were announced in [[1926]], but ground breaking was delayed until [[April 1]], [[1927]]. | The Alabama was built by Paramount Studio's Publix Theater division as an opulent "movie palace" for screening silent films. It is one of two extant theaters, along with Knoxville's Tennessee Theatre (1928), known to have been designed by the Chicago architecture firm of Graven and Mayger. Arthur G. Larson was the architect responsible for the design.<!--a June 24, 1927 ad for Brunswick-Kroeschell Refrigeration air conditioning equipment lists "C. W. & Geo. L. Rapp" as the architects ([http://ia601205.us.archive.org/BookReader/BookReaderImages.php?zip=/20/items/motion35moti/motion35moti_jp2.zip&file=motion35moti_jp2/motion35moti_1404.jp2 link])--> Construction plans for the Alabama were announced in [[1926]], but ground breaking was delayed until [[April 1]], [[1927]]. Paramount had planned to include the space now occupied by the [[Goldstein building]] at the corner of the block as part of the Alabama, but the owners refused to sell, forcing Paramount to redesign the Alabama as an L-shaped building instead of a rectangle. | ||

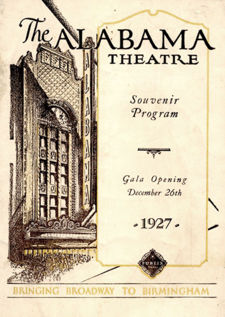

[[Image:1927 Alabama Theatre program.jpg|right|thumb|225px|Program from opening night]] | [[Image:1927 Alabama Theatre program.jpg|right|thumb|225px|Program from opening night]] | ||

After opening, then-2,500-seat theater eclipsed the year-old [[Ritz Theatre]], which seated 2,000, as the largest in the city, and replaced the [[Strand Theatre]] as the primary outlet for Paramount offerings. An opening preview for invited guests was held, as scheduled, on [[December 25|Christmas Day]], [[1927]], while the first feature, ''The Spotlight'', starring Esther Rawlson and Neil Hamilton, was screened on on [[December 26]]. Paramount President Adolph Zukor proclaimed it "'''The Showplace of the South'''", an appellation that soon appeared in gilt letters under the marquee. | |||

At its opening, the theater was managed by [[Sidney Dannenberg]], assisted by [[Steven Barutio]] and advertising promoter [[Larry Cowen]]. Feature film screenings were accompanied by live stage acts produced by Publix' team of John Murray Anderson, Frank Cambria, and Jack Partington. [[Ralph Pollack]] conducted the stage band, while [[Bruce Brummit]] led the pit orchestra and [[Joe Alexander]] manned the Wurlitzer organ. | At its opening, the theater was managed by [[Sidney Dannenberg]], assisted by [[Steven Barutio]] and advertising promoter [[Larry Cowen]]. Feature film screenings were accompanied by live stage acts produced by Publix' team of John Murray Anderson, Frank Cambria, and Jack Partington. [[Ralph Pollack]] conducted the stage band, while [[Bruce Brummit]] led the pit orchestra and [[Joe Alexander]] manned the Wurlitzer organ. | ||

The Alabama was one of fifteen Southern theaters sold by the Paramount-Publix Corporation in [[1932]] before the company went into receivership. The buyer was the independent Wilby-Kincey Theatres chain, which owned and operated the Alabama until [[1972]]. Theater workers, organized under the [[IATSE Local 78|Stagehands Union]], walked out when the new managers demanded longer working hours and assigned individual workers to operate equipment formerly done in teams of two. The ongoing labor dispute was suspected to be the motive for two bombings in the auditorium on [[October 15]] and [[December 25]] of that year. Neither explosion caused injury, though the second, which went off during a holiday screening of "A Farewell to Arms" with Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes, filled the auditorium with smoke and caused three ladies to faint. | |||

In [[1934]], the | |||

In June [[1933]] manager [[George Nealeans]] launched the Alabama Theatre chapter of the Mickey Mouse Club. | |||

In [[1934]], the [[1899]] [[Loveman's]] department store next door burned to the ground. The three foot thick firewall which Larson designed for that side of the Alabama is credited with saving the theatre from the fire. Stains on the ceiling from smoke that was pulled into the building from the street were visible until the theatre's [[1998]] restoration. | |||

In [[1935]] the Alabama Theatre hosted the [[Miss Alabama]] pageant for the first time. [[Stanleigh Malotte]] began his nearly 20-year career as house organist in [[1937]]. In [[1953]] the theater's projection system and screen were upgraded for CinemaScope presentations. The theatre hosted the world premiere of ''Young and Dangerous'' starring Birmingham native [[Lili Gentle]] on [[October 30]], [[1957]]. [[Cousin Cliff]] hosted the "[[Flying G Savers Club]]" shows on Saturday afternoons beginnning in October [[1959]]. | |||

The 1960s saw the Alabama broaden its horizons. The rescission of the city's [[segregation ordinances]] in [[1963]] meant that the theatre could admit African American patrons for the first time. In September [[1964]] the theater presented an "Electronovision Theatrofilm" simulcast of "Hamlet" with Richard Burton. In [[1965]] the city's first foreign film series, "Cinema Unlimited," was screened at the Alabama. The end of that decade marked the first American Theatre Organ Society project to begin restoring the theatre's pipe organ. | |||

===Decline and Re-opening=== | ===Decline and Re-opening=== | ||

The decline of downtown Birmingham through the | The decline of downtown Birmingham through the 1960s and 1970s saw the closing of most of the downtown's movie theaters. Wilby-Kencey sold the venue to ABC Southeastern Theatres. They contracted with [[A. H. Rogers & Sons Painting & Decorating Co.]] to perform some restoration work on the interior finishes. | ||

They sold it, in July [[1981]], to Plitt Southern Theatre Inc., a division of Chicago's Plitt Theatres chain. Plitt closed the Alabama in December of that year. "Sharky's Machine" starring Burt Reynolds was the last first-run feature to show at the Alabama Theatre. | |||

Plitt sold the Alabama to Birmingham's [[Cobb Theatres]] chain. On [[September 4]] Cobb vice president [[Norm Levinson]] inaugurated a series of current films at discounted ticket prices to lure patrons to the downtown theater, but the promotion was unsuccessful. After a few further attempts, Cobb sold the Alabama to [[Costa & Head]], developers working to [[Downtown revitalization|revitalize the downtown area]], in [[1984]]. Costa & Head initiated series of classic movies at the Alabama with some success, but ultimately filed for bankruptcy in [[1986]]. | |||

With the possibility of abandonment or demolition in sight, the [[Alabama Chapter of the American Theatre Organ Society]] (ATOS) sought permission to remove the pipe organ from the Alabama to save it, but Costa & Head's creditors deemed it the single most valuable item in the building and forbade its removal. In response the Alabama Chapter of ATOS began a fund-raising effort to buy the building, which, with a loan from [[Citizens Federal Savings Bank]], was successful. In [[1987]], Birmingham Landmarks, Inc. was formed to own and operate the Alabama rather than ATOS. The theatre was renamed the '''Alabama Theatre for the Performing Arts''' shortly thereafter. | |||

===Landmark status=== | ===Landmark status=== | ||

[[Image:Alabama Theatre Interior (HABS).jpg|right|thumb|300px|Interior in 1996, prior to restoration. Photograph by Jack Boucher (HABS)]] | [[Image:Alabama Theatre Interior (HABS).jpg|right|thumb|300px|Interior in 1996, prior to restoration. Photograph by Jack Boucher (HABS)]] | ||

On [[December 13]], [[1979]], the Alabama Theatre was added to the [[List of Buildings on the National Register of Historic Places|National Register of Historic Places]]. In [[1993]] the Alabama was designated the "official state historic theatre" by the Alabama legislature. [http://www.archives.state.al.us/kids_emblems/st_theat.html] In [[1998]], the Alabama underwent a complete cleaning and restoration including the seating, carpet and drapes. Smoke stains from the Loveman's fire, visible in the photograph at right, were carefully cleaned and refinished. New York | On [[December 13]], [[1979]], the Alabama Theatre was added to the [[List of Buildings on the National Register of Historic Places|National Register of Historic Places]]. In [[1993]] the Alabama was designated the "official state historic theatre" by the Alabama legislature. [http://www.archives.state.al.us/kids_emblems/st_theat.html] In [[1998]], the Alabama underwent a complete cleaning and restoration including the seating, carpet and drapes. Smoke stains from the Loveman's fire, visible in the photograph at right, were carefully cleaned and refinished. The New York-based firm Evergreene Architectural Arts restored the plaster finishes, stenciling and gilding as part of the $1.5 million project. | ||

Birmingham Landmarks continues to operate the Alabama. The group purchased the adjacent [[Goldstein building]] in [[1992]]. The [[Lyric Theatre]], a [[1914]] vaudeville theatre located across the street from the Alabama, was donated to them in [[1993]]. | Birmingham Landmarks continues to operate the Alabama. The group purchased the adjacent [[Goldstein building]] in [[1992]]. The [[Lyric Theatre]], a [[1914]] vaudeville theatre located across the street from the Alabama, was donated to them in [[1993]]. | ||

In [[2008]] the Alabama Theatre expanded its special-event facilities by opening the [[Hill Arts Center]] in the Goldstein building. The new center, accessible directly from the theater, features a 3,000 square-foot ballroom as well as a catering kitchen and two public lobbies. | In [[2008]] the Alabama Theatre expanded its special-event facilities by opening the [[Hill Arts Center]] in the Goldstein building. The new center, accessible directly from the theater, features a 3,000 square-foot ballroom as well as a catering kitchen and two public lobbies. | ||

In [[2011]], the Alabama was given the Building of the Year Award from the [[Alabama Architectural Foundation]] as the "building statewide that best exemplifies how architecture can provide a meaningful impact on the citizens of Alabama in the past, present and future." [https://alabamatheatre.com/about-the-alabama/] | |||

In [[2018]], Birmingham Landmarks had the original carpet pattern rewoven in wool, as the original had been. This new carpet was then put down throughout the non-stair areas of the mezzanine and balcony. Prior to that, only the uppermost hallway on the second balcony, outside the men's and ladies' lounges, still had a section of the original carpet. The carpet on the first balcony hallway was from the 1950s. The rest of the carpet had been replaced in the 1970s and again in [[1998]]. | |||

===Managers=== | ===Managers=== | ||

* [[Sidney Dannenberg]], [[ | * [[Sidney Dannenberg]], 1927– | ||

* [[ | * [[Vernon Reaver]], 1931 | ||

* [[Norris Hadaway]], | * [[Rolin Stonebrook]], September 1932– | ||

* [[Mack Russell]], | * [[George Nealeans]], June 1933 | ||

* [[Cecil McGlohon]], | * [[Francis Falkenburg]], 1936–1950 | ||

* [[Gary Tucker]], | * [[Norris Hadaway]], 1950–1956 | ||

* [[Cecil Whitmire]], | * [[Mack Russell]], 1956–1958 | ||

* [[Brant Beene]], | * [[Cecil McGlohon]], 1958–? | ||

* [[Gary Tucker]], 1972–1977 | |||

* [[Cecil Whitmire]], 1987–2010 | |||

* [[Brant Beene]], 2010–present | |||

==Mighty Wurlitzer Theatre Organ== | ==Mighty Wurlitzer Theatre Organ== | ||

{{Main|Mighty Wurlitzer Theatre Organ}} | |||

[[Image:Cecil Whitmire at organ.jpg|left|thumb|275px|Cecil Whitmire at the Mighty Wurlitzer in 2005. Photo by Hayneyz]] | [[Image:Cecil Whitmire at organ.jpg|left|thumb|275px|Cecil Whitmire at the Mighty Wurlitzer in 2005. Photo by Hayneyz]] | ||

[[Image:Alabama_Theater_Wurlitzer_keyboards.jpg|right|thumb|275px|Mighty Wurlitzer keyboards. Photo by Robert Matthews]] | [[Image:Alabama_Theater_Wurlitzer_keyboards.jpg|right|thumb|275px|Mighty Wurlitzer keyboards. Photo by Robert Matthews]] | ||

In order to provide music and sound effects for silent films, the Alabama was outfitted with a 4 manual, 20-rank Crawford Special-Publix One Mighty Wurlitzer theater organ from the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company of North Tonawanda, New York to the specifications of Jesse Crawford. | In order to provide music and sound effects for silent films, the Alabama was outfitted with a 4 manual, 20-rank Crawford Special-Publix One Mighty Wurlitzer theater organ (Opus 1783) from the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company of North Tonawanda, New York to the specifications of Jesse Crawford. | ||

Dubbed "Big Bertha", or simply "The Mighty Wurlitzer", it is one of 17 of its type ever built, and one of only three still installed in their original sites (The Denver Paramount and The Seattle Paramount have their original Publix 1's). The organ console is mounted on a screw lift that can bring it up to stage level or lower it out of sight to orchestra-floor level. Since its debut, Big Bertha has been expanded to 32 ranks and has seen the addition of multiple percussive and other mechanical effects. | Dubbed "Big Bertha", or simply "The Mighty Wurlitzer", it is one of 17 of its type ever built, and one of only three still installed in their original sites (The Denver Paramount and The Seattle Paramount have their original Publix 1's). The organ console is mounted on a screw lift that can bring it up to stage level or lower it out of sight to orchestra-floor level. Since its debut, Big Bertha has been expanded to 32 ranks and has seen the addition of multiple percussive and other mechanical effects. | ||

[[Joe Alexander]] was the first person to hold the title "house organist," but it was [[Lillian Truss]] who first played for the Mighty Wurlitzer for the public, during a preview on December 25, 1927. From the [[1936]] to [[1955]], the primary house organist was [[Stanleigh Malotte]]. When the Alabama began its classic movie series under Costa and Head in the mid-1980's, Cecil Whitmire became the house organist, a position he continued to hold until his retirement as organist in [[2007]]. Currently, [[Gary W. Jones]] is the House Organist. | |||

The organ is maintained by a crew of volunteers led by [[Larry Donaldson]]. Other crew members include [[Tom Cronier]], [[Andy Fox]], [[Lex Sorensen]], [[Karl Sorensen]], [[Bob Yuill]], [[Sabrina Summers]], [[Andy Gallien]], [[Pat Seitz]], and [[Garrett Godbey]]. | |||

==Architecture== | ==Architecture== | ||

[[Image:Alabama Theatre front.jpg|right|thumb|275px|Exterior of the theatre]] | [[Image:Alabama Theatre front.jpg|right|thumb|275px|Exterior of the theatre]] | ||

The front façade of the Alabama was intended as a tribute to New York's Paramount Theatre. It is composed of a monumental arch inset with terra-cotta detailing and surrounded by patterned brick. The elaborate interior, a highly-theatrical themed environment drawing liberally from many styles of architecture, is most heavily influenced by the Hispano-Moresque style. Materials used included marbles from Belgium, France and Italy, granite from Minnesota, terra-cotta fabricated in New York, and woodwork from Wisconsin, Florida and Louisiana. Interior furnishings include original paintings in oil and gilt decorative objects. Much of the plaster ornament is gilt or marbled. Elaborate light fixtures decorate the auditorium and | The front façade of the Alabama was intended as a tribute to New York's Paramount Theatre. It is composed of a monumental arch inset with terra-cotta detailing and surrounded by patterned brick. The elaborate interior, a highly-theatrical themed environment drawing liberally from many styles of architecture, is most heavily influenced by the Hispano-Moresque style. Materials used included marbles from Belgium, France and Italy, granite from Minnesota, terra-cotta fabricated in New York, and woodwork from Wisconsin, Florida and Louisiana. Interior furnishings include original paintings in oil and gilt decorative objects. Much of the plaster ornament, cast on site by Jacobson & Company of New York, is gilt or marbled. Elaborate light fixtures decorate the auditorium and lobbies. | ||

Like its predecessor, the [[Ritz Theatre]], the Alabama was one of the first air-conditioned buildings in Alabama. A cooling plant supplied by the Brunswick-Kroeschell Company pulled ambient air through grilles beneath the orchestra seats so it could be "washed, dried and then forced down through high overhead ducts". | |||

===Exterior signage=== | ===Exterior signage=== | ||

| Line 60: | Line 83: | ||

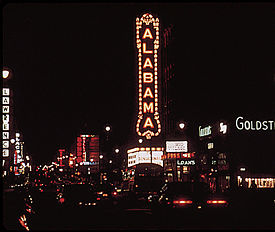

The Alabama Theatre originally featured two, identical, multi-story tall vertical signs spelling out "Alabama," one above the entrance on 3rd Avenue North and the other on the back of the theater along [[18th Street North|18th Street]]. Both signs were 60 feet tall by 12 feet wide with 4½-foot-tall letters illuminated by 2,338 lamps. | The Alabama Theatre originally featured two, identical, multi-story tall vertical signs spelling out "Alabama," one above the entrance on 3rd Avenue North and the other on the back of the theater along [[18th Street North|18th Street]]. Both signs were 60 feet tall by 12 feet wide with 4½-foot-tall letters illuminated by 2,338 lamps. | ||

In [[1957]], the sign on 3rd Avenue was taken down and reworked "to give new display effects." It is unknown precisely when the sign on 18th Street was permanently removed. | In [[1957]], the sign on 3rd Avenue was taken down and reworked "to give new display effects." It is unknown precisely when the sign on 18th Street was permanently removed. In [[2017]] Birmingham Landmarks partnered with [[REV Birmingham]] to compete in a grant program from Partners in Preservation for funds to restore the 18th street sign. The project was awarded $120,000 from the program, adding to locally-raised funds to commission [[Fravert Services]] to recreate the second sign for installation by [[December 31]]. | ||

The Alabama's marquee, used to advertise the current and upcoming shows, hangs between the entrance and the vertical sign on 3rd Avenue. The original 12-foot tall by 35-foot wide marquee projected 12 feet over the sidewalk and was very ornate, featuring hundreds of individual incandescent light bulbs. It was replaced by a much simpler marquee in [[1960]], featuring fluorescent lighting that makes it brighter and easier to maintain. It features two strips of chasing bulbs on red backgrounds, one at the top and one at the bottom, both wrapping around the entire marquee. | The Alabama's marquee, used to advertise the current and upcoming shows, hangs between the entrance and the vertical sign on 3rd Avenue. The original 12-foot tall by 35-foot wide marquee projected 12 feet over the sidewalk and was very ornate, featuring hundreds of individual incandescent light bulbs. It was replaced by a much simpler marquee in [[1960]], featuring fluorescent lighting that makes it brighter and easier to maintain. It features two strips of chasing bulbs on red backgrounds, one at the top and one at the bottom, both wrapping around the entire marquee. | ||

In June of 2018, the light bulbs in the 3rd Avenue marquee sign were replaced with LEDs. | |||

===Lobby areas=== | ===Lobby areas=== | ||

[[Image:Ala Theatre box office.jpg|right|thumb|325px| | [[File:1957-05 Alabama Theatre Sweet Shoppe.jpg|right|thumb|325px|The Sweet Shoppe in May 1957]] | ||

Patrons enter the Alabama through its ticket lobby, featuring a small, two-person ticket booth in the center and two sets of decorative mirror designs surrounded by lights. On the west wall is a larger ticket booth which is used for large, reserved seat events. This is the original location of the theatre concession stand. | [[Image:Ala Theatre box office.jpg|right|thumb|325px|The Alabama's enclosed ticket lobby in 2010]] | ||

Patrons enter the Alabama through its ticket lobby, featuring a small, two-person ticket booth in the center and two sets of decorative mirror designs surrounded by lights. On the west wall is a larger ticket booth which is used for large, reserved seat events. This is the original location of the theatre "Sweet Shoppe" concession stand. | |||

Upon purchasing their tickets, patrons proceed through the doors into the Hall of Mirrors. | Upon purchasing their tickets, patrons proceed through the doors into the three-story "Hall of Mirrors". Hanging from the center of the ceiling is a large, three dimensional, star-shaped chandelier made of strings of glass beads. The area also features a staircase up to the mezzanine. | ||

Straight ahead from the Hall of Mirrors, after passing under a "bridge" area where the current concession stand is located, is the main lobby. It is also three stories tall and features a large chandelier and gold-leafed ceiling. Here the main staircase goes up to the mezzanine, while another staircase descends under it to the lounge, where the main restrooms are located. An additional pair of restrooms are located under the second balcony. | Straight ahead from the Hall of Mirrors, after passing under a "bridge" area where the current concession stand is located, is the main lobby. It is also three stories tall and features a large chandelier and gold-leafed ceiling. Here the main staircase goes up to the mezzanine, while another staircase descends under it to the lounge, where the main restrooms are located. An additional pair of restrooms are located under the second balcony. | ||

| Line 93: | Line 119: | ||

===Phantom of the Opera=== | ===Phantom of the Opera=== | ||

{{main|Phantom of the Opera}} | {{main|Phantom of the Opera}} | ||

In [[1979]], the Alabama Chapter of ATOS held their first showing of the silent movie ''The Phantom of the Opera'', a [[1925]] film starring Lon Chaney. Accompaning the film on the Mighty Wurlitzer organ was Tom Helms, who wrote his own score for the movie. The movie and Helms have been back every year since then except [[1981]], when he performed it in Knoxville and New Orleans. The show usually takes place on the | In [[1979]], the Alabama Chapter of ATOS held their first showing of the silent movie ''The Phantom of the Opera'', a [[1925]] film starring Lon Chaney. Accompaning the film on the Mighty Wurlitzer organ was Tom Helms, who wrote his own score for the movie. The movie and Helms have been back every year since then except [[1981]], when he performed it in Knoxville and New Orleans. The show usually takes place on the weekend before Halloween. | ||

===Christmas at the Alabama=== | ===Christmas at the Alabama=== | ||

| Line 100: | Line 126: | ||

==Trivia== | ==Trivia== | ||

* The Alabama had 2,500 seats when it first opened in 1927. Later renovations replaced the seats on the main floor with larger ones, reducing the seat count to 2,200. (Source: Showplace of the South flyer, Birmingham Landmarks, 1991) | * The Alabama had 2,500 seats when it first opened in 1927. Later renovations replaced the seats on the main floor with larger ones, reducing the seat count to 2,200. (Source: Showplace of the South flyer, Birmingham Landmarks, 1991) | ||

* The Alabama's 22' x 40' screen is the largest in the state. | * The Alabama's 22' x 40' screen is the largest traditional (that is, non-IMAX style), indoor screen in the state. | ||

* For many years, the street address of the Alabama was mistakenly thought by the owners to be 1811 3rd Avenue North. Around 1991, Birmingham Landmarks discovered the error and corrected it to 1817. Street number 1811 | * For many years, the street address of the Alabama was mistakenly thought by the owners to be 1811 3rd Avenue North. Around 1991, Birmingham Landmarks discovered the error and corrected it to 1817. Street number 1811 actually belonged to the [[Goldstein's Furs]] retail space in the [[Goldstein building]] a few doors down from the Alabama entrance. That space is now operated by Birmingham Landmarks as the [[Hill Event Center]]. | ||

* The theater is rumored to be haunted by one or more [[Alabama Theatre ghosts|ghosts]]. | * The theater is rumored to be haunted by one or more [[Alabama Theatre ghosts|ghosts]]. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* "[http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/motionnew37moti_0163 Publix' New Birmingham Theatre Holds Formal Opening]" (January 14, 1928) ''Motion Picture News'' | * "[http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/motionnew37moti_0163 Publix' New Birmingham Theatre Holds Formal Opening]" (January 14, 1928) ''Motion Picture News'' | ||

* "Sign of the Times" (October 25, 1957) {{BPH}} | * Hadaway, R. Norris (November 7, 1952) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p4017coll2/id/434 Guided Tour Information]". typescript - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p4017coll2/id/462 Sign of the Times]" (October 25, 1957) {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Weaver, Emmett. "Alabama's Marquee Will Shed New Light" (May 12, 1960) {{BPH}} | * Weaver, Emmett. "Alabama's Marquee Will Shed New Light" (May 12, 1960) {{BPH}} | ||

* {{Satterfield-1976}} | * {{Satterfield-1976}} | ||

* Reeves, Garland (February 12, 1978) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p4017coll2/id/9928 Great Alabama Theatre battles to keep afloat]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Moore, Sally (September 20, 1979) "[http://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/63455a2d-f4fe-4f13-8bc2-724869820f8b/ Alabama Theatre]". National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form | |||

* Ingram, Charlie (March 12, 1987) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p4017coll2/id/9933 Society seeks to buy Alabama Theatre, needs $100,000 quickly]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Ryan, Shawn (April 23, 1987) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p4017coll2/id/9944 A Scrapbook filled with memories from the Alabama Theatre]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Whitmire, Cecil and Jeannie Hanks (2002) ''The Alabama Theatre: Showplace of the South''. Birmingham Landmarks ISBN 0310975124 | * Whitmire, Cecil and Jeannie Hanks (2002) ''The Alabama Theatre: Showplace of the South''. Birmingham Landmarks ISBN 0310975124 | ||

* "[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alabama_Theatre Alabama Theatre]" (April 27, 2006) Wikipedia - accessed April 27, 2006 | * "[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alabama_Theatre Alabama Theatre]" (April 27, 2006) Wikipedia - accessed April 27, 2006 | ||

* "Phantom of Alabama Theatre makes the occasional cameo." (October 30, 2006) {{BN}} | * "Phantom of Alabama Theatre makes the occasional cameo." (October 30, 2006) {{BN}} | ||

* Bennett, Jim (Fall 2013) "[http://www.jeffcohistory.com/newsletter_Oct_13_pg1.html Bomb Explodes In Sunday Show]" ''The Jefferson Journal''. Jefferson County Historical Society | |||

* Brock, Glenny (2015) ''The Alabama Theatre: Showplace of the South.'' Birmingham: Birmingham Landmarks Inc. ISBN 0996253556 | |||

* Carlton, Bob (November 2, 2017) "Alabama Theatre wins grant to reinstall historic sign." {{BN}} | |||

* Colurso, Mary (December 27, 2017) "[http://www.al.com/entertainment/index.ssf/2017/12/alabama_theatre_wurlitzer_orga_1.html Longtime volunteer's wizardly ways keep Alabama Theatre (and its Mighty Wurlitzer) running smooth]" {{BN}} | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 121: | Line 156: | ||

* [http://www.alabamatheatre.com Alabama Theatre] official website | * [http://www.alabamatheatre.com Alabama Theatre] official website | ||

* [http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/search/searchterm/Alabama%20Theatre/field/subjec/mode/exact/conn/and/order/nosort Alabama Theatre photographs and clippings] at the Birmingham Public Library archives. | * [http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/search/searchterm/Alabama%20Theatre/field/subjec/mode/exact/conn/and/order/nosort Alabama Theatre photographs and clippings] at the Birmingham Public Library archives. | ||

* [http:// | * [http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/al1203/ Alabama Theatre photographs and drawings] at the Historic American Buildings Survey. | ||

* [http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/bhamtheaters_main.htm Showplaces of the South] at Birmingham Rewound | * [http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/bhamtheaters_main.htm Showplaces of the South] at Birmingham Rewound | ||

* [http://www.archives.state.al.us/emblems/st_theat.html Alabama Historic Theatre] at the Alabama Department of Archives & History | * [http://www.archives.state.al.us/emblems/st_theat.html Alabama Historic Theatre] at the Alabama Department of Archives & History | ||

| Line 130: | Line 165: | ||

[[Category:1927 buildings]] | [[Category:1927 buildings]] | ||

[[Category:1927 establishments]] | [[Category:1927 establishments]] | ||

[[Category:National Register of Historic Places]] | [[Category:National Register of Historic Places in Birmingham]] | ||

[[Category:Fallout shelters]] | [[Category:Fallout shelters]] | ||

[[Category:Haunts]] | [[Category:Haunts]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:40, 5 September 2023

The Alabama Theatre, is a 2,000 seat "movie palace" opened by Paramount Studios in 1927 at 1817 3rd Avenue North, and a major landmark in downtown Birmingham's "Theater District".

Paramount constructed the theater as its first-run showplace, overtaking the Strand and Galax in that role. It was constructed to showcase the silent films of the era, with staging for live performances which Publix produced to accompany feature screenings at its largest theaters. A feature of the house is its "Mighty Wurlitzer" theater organ, the console of which can be raised to stage level for recitals or lowered out of sight to accompany films.

Now painstakingly restored, the Alabama is operated by Birmingham Landmarks, a non-profit corporation founded by Cecil Whitmire in 1987. The Alabama Theatre hosts numerous live concerts and classic movie screenings, as well as recitals, weddings and private events throughout the year.

History

The Alabama was built by Paramount Studio's Publix Theater division as an opulent "movie palace" for screening silent films. It is one of two extant theaters, along with Knoxville's Tennessee Theatre (1928), known to have been designed by the Chicago architecture firm of Graven and Mayger. Arthur G. Larson was the architect responsible for the design. Construction plans for the Alabama were announced in 1926, but ground breaking was delayed until April 1, 1927. Paramount had planned to include the space now occupied by the Goldstein building at the corner of the block as part of the Alabama, but the owners refused to sell, forcing Paramount to redesign the Alabama as an L-shaped building instead of a rectangle.

After opening, then-2,500-seat theater eclipsed the year-old Ritz Theatre, which seated 2,000, as the largest in the city, and replaced the Strand Theatre as the primary outlet for Paramount offerings. An opening preview for invited guests was held, as scheduled, on Christmas Day, 1927, while the first feature, The Spotlight, starring Esther Rawlson and Neil Hamilton, was screened on on December 26. Paramount President Adolph Zukor proclaimed it "The Showplace of the South", an appellation that soon appeared in gilt letters under the marquee.

At its opening, the theater was managed by Sidney Dannenberg, assisted by Steven Barutio and advertising promoter Larry Cowen. Feature film screenings were accompanied by live stage acts produced by Publix' team of John Murray Anderson, Frank Cambria, and Jack Partington. Ralph Pollack conducted the stage band, while Bruce Brummit led the pit orchestra and Joe Alexander manned the Wurlitzer organ.

The Alabama was one of fifteen Southern theaters sold by the Paramount-Publix Corporation in 1932 before the company went into receivership. The buyer was the independent Wilby-Kincey Theatres chain, which owned and operated the Alabama until 1972. Theater workers, organized under the Stagehands Union, walked out when the new managers demanded longer working hours and assigned individual workers to operate equipment formerly done in teams of two. The ongoing labor dispute was suspected to be the motive for two bombings in the auditorium on October 15 and December 25 of that year. Neither explosion caused injury, though the second, which went off during a holiday screening of "A Farewell to Arms" with Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes, filled the auditorium with smoke and caused three ladies to faint.

In June 1933 manager George Nealeans launched the Alabama Theatre chapter of the Mickey Mouse Club.

In 1934, the 1899 Loveman's department store next door burned to the ground. The three foot thick firewall which Larson designed for that side of the Alabama is credited with saving the theatre from the fire. Stains on the ceiling from smoke that was pulled into the building from the street were visible until the theatre's 1998 restoration.

In 1935 the Alabama Theatre hosted the Miss Alabama pageant for the first time. Stanleigh Malotte began his nearly 20-year career as house organist in 1937. In 1953 the theater's projection system and screen were upgraded for CinemaScope presentations. The theatre hosted the world premiere of Young and Dangerous starring Birmingham native Lili Gentle on October 30, 1957. Cousin Cliff hosted the "Flying G Savers Club" shows on Saturday afternoons beginnning in October 1959.

The 1960s saw the Alabama broaden its horizons. The rescission of the city's segregation ordinances in 1963 meant that the theatre could admit African American patrons for the first time. In September 1964 the theater presented an "Electronovision Theatrofilm" simulcast of "Hamlet" with Richard Burton. In 1965 the city's first foreign film series, "Cinema Unlimited," was screened at the Alabama. The end of that decade marked the first American Theatre Organ Society project to begin restoring the theatre's pipe organ.

Decline and Re-opening

The decline of downtown Birmingham through the 1960s and 1970s saw the closing of most of the downtown's movie theaters. Wilby-Kencey sold the venue to ABC Southeastern Theatres. They contracted with A. H. Rogers & Sons Painting & Decorating Co. to perform some restoration work on the interior finishes.

They sold it, in July 1981, to Plitt Southern Theatre Inc., a division of Chicago's Plitt Theatres chain. Plitt closed the Alabama in December of that year. "Sharky's Machine" starring Burt Reynolds was the last first-run feature to show at the Alabama Theatre.

Plitt sold the Alabama to Birmingham's Cobb Theatres chain. On September 4 Cobb vice president Norm Levinson inaugurated a series of current films at discounted ticket prices to lure patrons to the downtown theater, but the promotion was unsuccessful. After a few further attempts, Cobb sold the Alabama to Costa & Head, developers working to revitalize the downtown area, in 1984. Costa & Head initiated series of classic movies at the Alabama with some success, but ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 1986.

With the possibility of abandonment or demolition in sight, the Alabama Chapter of the American Theatre Organ Society (ATOS) sought permission to remove the pipe organ from the Alabama to save it, but Costa & Head's creditors deemed it the single most valuable item in the building and forbade its removal. In response the Alabama Chapter of ATOS began a fund-raising effort to buy the building, which, with a loan from Citizens Federal Savings Bank, was successful. In 1987, Birmingham Landmarks, Inc. was formed to own and operate the Alabama rather than ATOS. The theatre was renamed the Alabama Theatre for the Performing Arts shortly thereafter.

Landmark status

On December 13, 1979, the Alabama Theatre was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1993 the Alabama was designated the "official state historic theatre" by the Alabama legislature. [1] In 1998, the Alabama underwent a complete cleaning and restoration including the seating, carpet and drapes. Smoke stains from the Loveman's fire, visible in the photograph at right, were carefully cleaned and refinished. The New York-based firm Evergreene Architectural Arts restored the plaster finishes, stenciling and gilding as part of the $1.5 million project.

Birmingham Landmarks continues to operate the Alabama. The group purchased the adjacent Goldstein building in 1992. The Lyric Theatre, a 1914 vaudeville theatre located across the street from the Alabama, was donated to them in 1993.

In 2008 the Alabama Theatre expanded its special-event facilities by opening the Hill Arts Center in the Goldstein building. The new center, accessible directly from the theater, features a 3,000 square-foot ballroom as well as a catering kitchen and two public lobbies.

In 2011, the Alabama was given the Building of the Year Award from the Alabama Architectural Foundation as the "building statewide that best exemplifies how architecture can provide a meaningful impact on the citizens of Alabama in the past, present and future." [2]

In 2018, Birmingham Landmarks had the original carpet pattern rewoven in wool, as the original had been. This new carpet was then put down throughout the non-stair areas of the mezzanine and balcony. Prior to that, only the uppermost hallway on the second balcony, outside the men's and ladies' lounges, still had a section of the original carpet. The carpet on the first balcony hallway was from the 1950s. The rest of the carpet had been replaced in the 1970s and again in 1998.

Managers

- Sidney Dannenberg, 1927–

- Vernon Reaver, 1931

- Rolin Stonebrook, September 1932–

- George Nealeans, June 1933

- Francis Falkenburg, 1936–1950

- Norris Hadaway, 1950–1956

- Mack Russell, 1956–1958

- Cecil McGlohon, 1958–?

- Gary Tucker, 1972–1977

- Cecil Whitmire, 1987–2010

- Brant Beene, 2010–present

Mighty Wurlitzer Theatre Organ

In order to provide music and sound effects for silent films, the Alabama was outfitted with a 4 manual, 20-rank Crawford Special-Publix One Mighty Wurlitzer theater organ (Opus 1783) from the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company of North Tonawanda, New York to the specifications of Jesse Crawford.

Dubbed "Big Bertha", or simply "The Mighty Wurlitzer", it is one of 17 of its type ever built, and one of only three still installed in their original sites (The Denver Paramount and The Seattle Paramount have their original Publix 1's). The organ console is mounted on a screw lift that can bring it up to stage level or lower it out of sight to orchestra-floor level. Since its debut, Big Bertha has been expanded to 32 ranks and has seen the addition of multiple percussive and other mechanical effects.

Joe Alexander was the first person to hold the title "house organist," but it was Lillian Truss who first played for the Mighty Wurlitzer for the public, during a preview on December 25, 1927. From the 1936 to 1955, the primary house organist was Stanleigh Malotte. When the Alabama began its classic movie series under Costa and Head in the mid-1980's, Cecil Whitmire became the house organist, a position he continued to hold until his retirement as organist in 2007. Currently, Gary W. Jones is the House Organist.

The organ is maintained by a crew of volunteers led by Larry Donaldson. Other crew members include Tom Cronier, Andy Fox, Lex Sorensen, Karl Sorensen, Bob Yuill, Sabrina Summers, Andy Gallien, Pat Seitz, and Garrett Godbey.

Architecture

The front façade of the Alabama was intended as a tribute to New York's Paramount Theatre. It is composed of a monumental arch inset with terra-cotta detailing and surrounded by patterned brick. The elaborate interior, a highly-theatrical themed environment drawing liberally from many styles of architecture, is most heavily influenced by the Hispano-Moresque style. Materials used included marbles from Belgium, France and Italy, granite from Minnesota, terra-cotta fabricated in New York, and woodwork from Wisconsin, Florida and Louisiana. Interior furnishings include original paintings in oil and gilt decorative objects. Much of the plaster ornament, cast on site by Jacobson & Company of New York, is gilt or marbled. Elaborate light fixtures decorate the auditorium and lobbies.

Like its predecessor, the Ritz Theatre, the Alabama was one of the first air-conditioned buildings in Alabama. A cooling plant supplied by the Brunswick-Kroeschell Company pulled ambient air through grilles beneath the orchestra seats so it could be "washed, dried and then forced down through high overhead ducts".

Exterior signage

The Alabama Theatre originally featured two, identical, multi-story tall vertical signs spelling out "Alabama," one above the entrance on 3rd Avenue North and the other on the back of the theater along 18th Street. Both signs were 60 feet tall by 12 feet wide with 4½-foot-tall letters illuminated by 2,338 lamps.

In 1957, the sign on 3rd Avenue was taken down and reworked "to give new display effects." It is unknown precisely when the sign on 18th Street was permanently removed. In 2017 Birmingham Landmarks partnered with REV Birmingham to compete in a grant program from Partners in Preservation for funds to restore the 18th street sign. The project was awarded $120,000 from the program, adding to locally-raised funds to commission Fravert Services to recreate the second sign for installation by December 31.

The Alabama's marquee, used to advertise the current and upcoming shows, hangs between the entrance and the vertical sign on 3rd Avenue. The original 12-foot tall by 35-foot wide marquee projected 12 feet over the sidewalk and was very ornate, featuring hundreds of individual incandescent light bulbs. It was replaced by a much simpler marquee in 1960, featuring fluorescent lighting that makes it brighter and easier to maintain. It features two strips of chasing bulbs on red backgrounds, one at the top and one at the bottom, both wrapping around the entire marquee.

In June of 2018, the light bulbs in the 3rd Avenue marquee sign were replaced with LEDs.

Lobby areas

Patrons enter the Alabama through its ticket lobby, featuring a small, two-person ticket booth in the center and two sets of decorative mirror designs surrounded by lights. On the west wall is a larger ticket booth which is used for large, reserved seat events. This is the original location of the theatre "Sweet Shoppe" concession stand.

Upon purchasing their tickets, patrons proceed through the doors into the three-story "Hall of Mirrors". Hanging from the center of the ceiling is a large, three dimensional, star-shaped chandelier made of strings of glass beads. The area also features a staircase up to the mezzanine.

Straight ahead from the Hall of Mirrors, after passing under a "bridge" area where the current concession stand is located, is the main lobby. It is also three stories tall and features a large chandelier and gold-leafed ceiling. Here the main staircase goes up to the mezzanine, while another staircase descends under it to the lounge, where the main restrooms are located. An additional pair of restrooms are located under the second balcony.

Auditorium

The auditorium is five stories tall at its highest point and the brown plaster walls and ceiling are decorated predominantly in red and green. The ceiling features several lit domes, the largest at the top of the ceiling. Additional domes are found at the rear of the balcony at the projection booth and under the main balcony above the mezzanine and main floor. All domes, the proscenium arch around the stage, the front of the organ pipe chambers, and other areas are lit with red, blue, and amber light bulbs. Each color of bulb can be individually dimmed to provide a variety of colors in these areas.

The auditorium features three seating levels: the main floor, the mezzanine, and the balcony. The balcony is further divided by level walkways into the dress circle (the first three rows), the first balcony, and the second balcony. The final row of the balcony is about two stories above the first row and 180 feet from the movie screen.

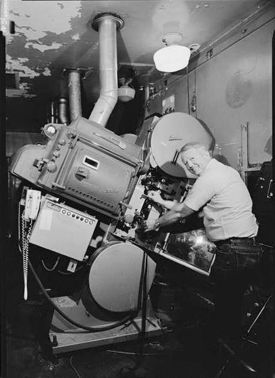

Projection room

The theatre's projection room, located behind the top-most level of the auditorium, above the lobbies, originally housed four massive carbon arc lamp projectors and at least two carbon arc lamp spotlights. The number of projectors was later reduced to two. The projection room features its own bathroom and access to both the roof and theatre attic, from which the light bulbs for the auditorium domes are changed.

Recurring events

The Alabama has been home to many recurring events of which Birmingham residents have fond memories.

Mickey Mouse Club

One of the things the Alabama was known for in its early days was its Mickey Mouse Club, which was formed in 1933. Meetings were held every Saturday, where the children would perform for each other, watch Mickey Mouse cartoons, and participate in other activities. The Club also sponsored food and toy drives for the underprivileged. By 1935, the Club had over 7,000 members, making it the biggest Mickey Mouse Club in the world. Membership eventually peaked at over 18,000 before the Club closed almost ten years after it was formed.

Miss Alabama Pageant

Another regular event at the Alabama was the Miss Alabama pageant. From 1935 to 1948, the rules of the Miss America pageant allowed multiple contestants per state. The Alabama Theatre hosted the Miss Birmingham pageant in those years. When the rules were changed in 1949, the Alabama became host to the Miss Alabama pageant and continued to do so through 1966.

Phantom of the Opera

In 1979, the Alabama Chapter of ATOS held their first showing of the silent movie The Phantom of the Opera, a 1925 film starring Lon Chaney. Accompaning the film on the Mighty Wurlitzer organ was Tom Helms, who wrote his own score for the movie. The movie and Helms have been back every year since then except 1981, when he performed it in Knoxville and New Orleans. The show usually takes place on the weekend before Halloween.

Christmas at the Alabama

In the late 1980s, Birmingham Landmarks started an annual Christmas show. It was divided into two acts. One act told the story of Jesus' birth, narrated straight from the Books of Matthew and Luke and interspersed with performances of traditional Christmas hymns and inspirational songs. The second act was of a more secular nature, the storyline being of a child wishing for snow on Christmas in Birmingham — an unlikely event. The show generally closed with his or her wish coming true and Santa leading the entire audience and cast singing "White Christmas" while thousands of white Christmas tree lights lit the auditorium. Birmingham Landmarks ceased production on the show in the mid-1990s.

Trivia

- The Alabama had 2,500 seats when it first opened in 1927. Later renovations replaced the seats on the main floor with larger ones, reducing the seat count to 2,200. (Source: Showplace of the South flyer, Birmingham Landmarks, 1991)

- The Alabama's 22' x 40' screen is the largest traditional (that is, non-IMAX style), indoor screen in the state.

- For many years, the street address of the Alabama was mistakenly thought by the owners to be 1811 3rd Avenue North. Around 1991, Birmingham Landmarks discovered the error and corrected it to 1817. Street number 1811 actually belonged to the Goldstein's Furs retail space in the Goldstein building a few doors down from the Alabama entrance. That space is now operated by Birmingham Landmarks as the Hill Event Center.

- The theater is rumored to be haunted by one or more ghosts.

References

- "Publix' New Birmingham Theatre Holds Formal Opening" (January 14, 1928) Motion Picture News

- Hadaway, R. Norris (November 7, 1952) "Guided Tour Information". typescript - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Sign of the Times" (October 25, 1957) Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Weaver, Emmett. "Alabama's Marquee Will Shed New Light" (May 12, 1960) Birmingham Post-Herald

- Satterfield, Carolyn Green (1976) Historic Sites of Jefferson County, Alabama. Birmingham: Jefferson County Historical Commission/Gray Printing Company

- Reeves, Garland (February 12, 1978) "Great Alabama Theatre battles to keep afloat" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Moore, Sally (September 20, 1979) "Alabama Theatre". National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

- Ingram, Charlie (March 12, 1987) "Society seeks to buy Alabama Theatre, needs $100,000 quickly" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Ryan, Shawn (April 23, 1987) "A Scrapbook filled with memories from the Alabama Theatre" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Whitmire, Cecil and Jeannie Hanks (2002) The Alabama Theatre: Showplace of the South. Birmingham Landmarks ISBN 0310975124

- "Alabama Theatre" (April 27, 2006) Wikipedia - accessed April 27, 2006

- "Phantom of Alabama Theatre makes the occasional cameo." (October 30, 2006) The Birmingham News

- Bennett, Jim (Fall 2013) "Bomb Explodes In Sunday Show" The Jefferson Journal. Jefferson County Historical Society

- Brock, Glenny (2015) The Alabama Theatre: Showplace of the South. Birmingham: Birmingham Landmarks Inc. ISBN 0996253556

- Carlton, Bob (November 2, 2017) "Alabama Theatre wins grant to reinstall historic sign." The Birmingham News

- Colurso, Mary (December 27, 2017) "Longtime volunteer's wizardly ways keep Alabama Theatre (and its Mighty Wurlitzer) running smooth" The Birmingham News

See also

External links

- Alabama Theatre official website

- Alabama Theatre photographs and clippings at the Birmingham Public Library archives.

- Alabama Theatre photographs and drawings at the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Showplaces of the South at Birmingham Rewound

- Alabama Historic Theatre at the Alabama Department of Archives & History

- Alabama Theatre Organ website