Lyric Theatre: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Mark Taylor (talk | contribs) |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

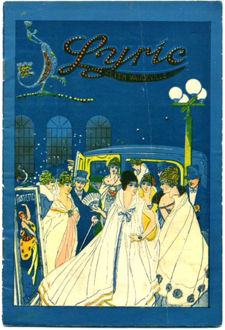

[[Image:Lyric_Theatre_1930.jpg|right| | :''This article is about the landmark theater opened in 1914 on 3rd Avenue North, for the former cinema on 2nd Avenue, see [[Lyric Theatre (2nd Avenue)]].'' | ||

[[Image:Lyric_Theatre_1930.jpg|right|575px|thumbnail|The Lyric in 1930 {{BPL permission caption|http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll6,1354}}]] | |||

The '''Lyric Theatre''' is a former vaudeville and movie theater constructed in [[1914]] at 1800 [[3rd Avenue North]] on the corner of [[18th Street North]]. The theater is adjoined by a [[Lyric Building|Lyric Office Building]], which was constructed simultaneously. | The '''Lyric Theatre''' is a former vaudeville and movie theater constructed in [[1914]] at 1800 [[3rd Avenue North]] on the corner of [[18th Street North]]. The theater is adjoined by a [[Lyric Building|Lyric Office Building]], which was constructed simultaneously. | ||

| Line 7: | Line 8: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

[[File:Louis Clark.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Louis V. Clark]] | |||

===Opening=== | ===Opening=== | ||

[[Image:Lyric Theatre 1912.jpg|right|thumb| | [[Image:Lyric Theatre 1912.jpg|right|thumb|325px|The theatre's office building under construction in 1912. Photo by O. V. Hunt {{BPL permission caption|http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll6,1657}}]] | ||

[[Image:Lyric interior 1914.jpg|right|thumb| | [[Image:Lyric interior 1914.jpg|right|thumb|325px|The auditorium of the Lyric on opening week]] | ||

The development of the Lyric Theatre began when real-estate developer [[Louis V. Clark]] purchased three adjoining lots and hired the [[Hendon Hetrack Construction Company]]<!--Moore-1922 indicates that the theatre was built by the F. W. Mark Construction Company--> to construct a six-story office building and theater on the property. The office building is a concrete frame and the auditorium is spanned with riveted hot-rolled steel trusses. | The development of the Lyric Theatre began when real-estate developer [[Louis V. Clark]] purchased three adjoining lots and hired the [[Hendon Hetrack Construction Company]]<!--Moore-1922 indicates that the theatre was built by the F. W. Mark Construction Company--> to construct a six-story office building and theater on the property. The office building is a concrete frame and the auditorium is spanned with riveted hot-rolled steel trusses. | ||

Clark formed a partnership with Jake Wells to operate the | Clark formed a partnership with Jake Wells to operate the theater. Wells already owned and managed a number of theaters across the South, including the [[Bijou Theatre|Bijou]] and [[Orpheum Theatre]]s, opposite each other at 3rd Avenue and [[17th Street North]]. Wells had hired architect C. K. Howell of Richmond, Virginia, to design renovations to the Orpheum in [[1912]]. Howell's association with the B. F. Keith circuit and with Wells in particular indicate that he was probably involved in the design of the Lyric. The interior design is also a near-identical match to the Wells Theatre which opened in [[1913]] in Norfolk, Virginia. That building is credited to E. C. Horn & Sons of New York, New York. | ||

The Lyric originally had 1,583 seats spread across the main floor, two steep balconies, and two opera boxes. A center section at the front of the stage had a water tank underneath for aquatic shows (and to hold ice for a rudimentary attempt at providing air conditioning). A gold-leafed and painted asbestos curtain hung on the stage beneath a proscenium featuring a large mural known as ''The Allegory of the Muses'', which was painted by local artist [[Harry Hawkins]]. Beneath the stage are a series of dressing rooms, each about eight feet square with sinks in the corners. | The Lyric originally had 1,583 seats spread across the main floor, two steep balconies, and two opera boxes. A center section at the front of the stage had a water tank underneath for aquatic shows (and to hold ice for a rudimentary attempt at providing air conditioning). A gold-leafed and painted asbestos curtain hung on the stage beneath a proscenium featuring a large mural known as ''The Allegory of the Muses'', which was painted by local artist [[Harry Hawkins]]. Beneath the stage are a series of dressing rooms, each about eight feet square with sinks in the corners. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 31: | ||

"The Lyric Company" with Hoblitzelle as president, secured affiliations with the Orpheum Circuit, B. F. Keith's circuit, United Booking Offices of America, and the Western Vaudeville Manager's Association as well as his own Interstate Amusement Company. Stars such as Sophie Tucker, Gus Edward's Kid Kabaret with George Jessel and Eddie Cantor, Will Rogers, the Keaton Family Acrobats (with Buster Keaton), Milton Berle, Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Belle Baker, the Marx Brothers, Lottie Mayer's "Neptune Gardens" water divers, Marshall Montgomery, Pat Rooney and Marion Bent, and Mae West appeared on stage. | "The Lyric Company" with Hoblitzelle as president, secured affiliations with the Orpheum Circuit, B. F. Keith's circuit, United Booking Offices of America, and the Western Vaudeville Manager's Association as well as his own Interstate Amusement Company. Stars such as Sophie Tucker, Gus Edward's Kid Kabaret with George Jessel and Eddie Cantor, Will Rogers, the Keaton Family Acrobats (with Buster Keaton), Milton Berle, Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Belle Baker, the Marx Brothers, Lottie Mayer's "Neptune Gardens" water divers, Marshall Montgomery, Pat Rooney and Marion Bent, and Mae West appeared on stage. | ||

[[W. S. Crosbie]] was the local manager in charge, with [[Al Plante]] as musical director of the '''Lyric Wonder Orchestra'''. Daily performances were scheduled for 2:30, 7:15 and 9:10, with two matinees (1:15 and 3:15) on Saturdays. Under Hoblitzelle's orders, all performances were guaranteed to be free of offensive words, expressions and situations. After motion pictures became popular, the Lyric pared its live schedule down to five new acts per week. | [[W. S. Crosbie]] was the local manager in charge, with [[Al Plante]] as musical director of the '''Lyric Wonder Orchestra'''. Daily performances were scheduled for 2:30, 7:15 and 9:10, with two matinees (1:15 and 3:15) on Saturdays. Under Hoblitzelle's orders, all performances were guaranteed to be free of offensive words, expressions and situations. With shows prohibited on Sundays, the Lyric hosted sermons by [[Independent Presbyterian Church]] pastor [[Henry Edmonds]] at 8:00 PM each week. After motion pictures became popular, the Lyric pared its live schedule down to five new acts per week. | ||

[[Image:Lyric lobby 1924.jpg|right|thumb|275px|1924 lobby advertisement for a screening of ''The Iron Horse'']] | [[Image:Lyric lobby 1924.jpg|right|thumb|275px|1924 lobby advertisement for a screening of ''The Iron Horse'']] | ||

In the early 1920s the Lyric started to see more competition. The [[Masonic Temple Theater]] was completed in [[1922]] and the [[Ritz Theater|Ritz]] and [[Empire Theater]]s opened in [[1926]]. After the completion of the larger air-conditioned Ritz, the Lyric permanently lost its status the grandest Vaudeville hall in Birmingham. One of its last major shows was the Birmingham premiere of "[[Men of Steel]]", a silent feature that had been filmed in [[Ensley]], accompanied by an "augmented orchestra". Bob O'Donnell of the Interstate Amusement Company reported to the distributor that it was breaking every record for receipts with standing room only from 2:00 PM until closing with immediate plans to hold the picture over for a second week. | In the early 1920s the Lyric started to see more competition. The [[Masonic Temple Theater]] was completed in [[1922]] and the [[Ritz Theater|Ritz]] and [[Empire Theater]]s opened in [[1926]]. The Keith circuit continued to bring weekly touring acts to the Lyric, with Pathé newsreels and Fox Film Corp. comedies screened before the stage show. | ||

After the completion of the larger air-conditioned Ritz, the Lyric permanently lost its status the grandest Vaudeville hall in Birmingham. One of its last major shows was the Birmingham premiere of "[[Men of Steel]]", a silent feature that had been filmed in [[Ensley]], accompanied by an "augmented orchestra". Bob O'Donnell of the Interstate Amusement Company reported to the distributor that it was breaking every record for receipts with standing room only from 2:00 PM until closing with immediate plans to hold the picture over for a second week. | |||

On Sunday evenings the theatre was used by the newly-formed [[Independent Presbyterian Church]]. A Kilgen opus 3459 size 2/4 theater organ was installed in [[1925]]. The touring "A. B. Marcus Revue" held court at the Lyric in [[1926]] with a large cast and chorus line. The Lyric hosted its own stock dramatic troupes in the off-season, including one with [[John McFarland]] and [[Katherine Comeges]]<!--or "Kathleen Connegs"--> as its stars. [[Russell Filmore]]'s [[Favorite Players]] with [[Jerome Cowan]] took to the stage with their popular light comedy from [[1927]] to [[1930]]. | On Sunday evenings the theatre was used by the newly-formed [[Independent Presbyterian Church]]. A Kilgen opus 3459 size 2/4 theater organ was installed in [[1925]]. The touring "A. B. Marcus Revue" held court at the Lyric in [[1926]] with a large cast and chorus line. The Lyric hosted its own stock dramatic troupes in the off-season, including one with [[John McFarland]] and [[Katherine Comeges]]<!--or "Kathleen Connegs"--> as its stars. [[Russell Filmore]]'s [[Favorite Players]] with [[Jerome Cowan]] took to the stage with their popular light comedy from [[1927]] to [[1930]]. | ||

===Decline=== | ===Decline=== | ||

The Lyric continued to operate successfully up until the [[Great Depression]]. With his funds overextended, Wells lost his chain of theaters and ultimately committed suicide. Ownership of the Lyric reverted to the mortgage company which leased it to the | The Lyric continued to operate successfully up until the [[Great Depression]]. With his funds overextended, Wells lost his chain of theaters and ultimately committed suicide. Ownership of the Lyric reverted to the mortgage company which leased it to the Shubert organization. The Lyric continued to present vaudeville acts, but the Depression and competition from movies and radio led to its decline and closure in [[1930]] or [[1931]]. | ||

In [[1932]], brothers Ben and [[L. A. Stein]] of Jacksonville, Florida reopened the Lyric as a movie theater. They installed a new Western Electric sound system and other refurbishments and scheduled four feature films each week, beginning with Will Rogers in "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" on [[April 25]] of that year. Ben returned to Florida while his brother remained in Birmingham as manager. Later the same year it was leased to the Paramount and the Wilby-Kincey circuit to operate it as a second run theater, often showing movies that had their local premieres across the street at the [[Alabama Theatre|Alabama]]. | In [[1932]], brothers Ben and [[L. A. Stein]] of Jacksonville, Florida reopened the Lyric as a movie theater. They installed a new Western Electric sound system and other refurbishments and scheduled four feature films each week, beginning with Will Rogers in "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" on [[April 25]] of that year. Ben returned to Florida while his brother remained in Birmingham as manager. Later the same year it was leased to the Paramount and the Wilby-Kincey circuit to operate it as a second run theater, often showing movies that had their local premieres across the street at the [[Alabama Theatre|Alabama]]. | ||

In October 1932, the [[Communist Party USA District 17]] hosted a rally for the [[1932 general election]] at the Lyric. Scheduled speaker Clarence Hathaway did not appear because of his arrest the previous night in New Orleans, Louisiana. In his stead [[Fred Keith]] spoke on issues relating to the election, the party's [[Unemployed Workers Movement]], and the trial of the [[Scottsboro boys]]. The meeting was interrupted by a smoke bomb tossed into the auditorium by a [[Ku Klux Klan]] member. | |||

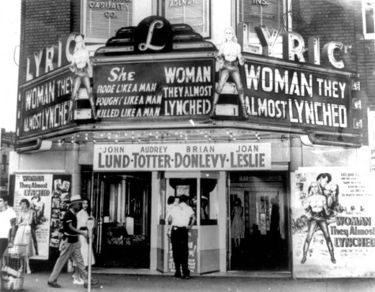

[[Image:Lyric marquee 1953.jpg|left|thumb|375px|The Lyric's marquee in 1953]] | [[Image:Lyric marquee 1953.jpg|left|thumb|375px|The Lyric's marquee in 1953]] | ||

The Lyric received another major renovation with new projection equipment in the early 1940s while [[Oliver Naylor]] was manager. In June [[1945]] [[Ervin Jackson & Associates]] bought the Lyric out of foreclosure for $400,000. They extended its lease it to the [[Waters Theater Company]], headed by [[Newman Waters, Sr]]. which continued its association with Paramount as a second-run house. In [[1950]] Waters turned the lease over to the [[Acme | The Lyric received another major renovation with new projection equipment in the early 1940s while [[Oliver Naylor]] was manager. In June [[1945]] [[Ervin Jackson & Associates]] bought the Lyric out of foreclosure for $400,000. They extended its lease it to the [[Waters Theater Company]], headed by [[Newman Waters, Sr]]. which continued its association with Paramount as a second-run house. In [[1950]] Waters turned the lease over to the [[Acme Theatres]] chain which also operated the [[Melba Theater]], [[Empire Theater]], [[Galax Theater]] and [[Royal Theater]]. | ||

The opera boxes were removed in [[1954]] under [[Bill O'Neill]]'s tenure as manager in order to accommodate a 15' tall by 36' wide screen for CinemaScope films. O'Neill also brought back live performances, with a weekly 11 PM "Saturday Night Jamboree" hosted by "Uncle" [[Jim Atkins]] and broadcast live on [[WBRC-AM]]. Among the musicians taking the stage in the 1950s were Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. | The opera boxes were removed in [[1954]] under [[Bill O'Neill]]'s tenure as manager in order to accommodate a 15' tall by 36' wide screen for CinemaScope films. O'Neill also brought back live performances, with a weekly 11 PM "Saturday Night Jamboree" hosted by "Uncle" [[Jim Atkins]] and broadcast live on [[WBRC-AM]]. Among the musicians taking the stage in the 1950s were Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. | ||

The theater closed its doors again | [[Henry Hury]] took over management for Acme some time later. The theater closed its doors again when the exhibitor lost its lease. The last day of operation was Sunday, [[October 2]], [[1960]]. The adjoining office building remained active with businesses such as the [[House of $8.50 Eyeglasses]]. [[Congress of Racial Equality]] photographer Bob Adelman documented the leftover "Colored Balcony" sign on [[18th Street North]] in [[1963]]. | ||

===Later life=== | ===Later life=== | ||

[[Image:Grand Bijou ad.jpg|right|thumb| | [[Image:Grand Bijou ad.jpg|right|thumb|175px|1973 ad for the opening of the "Grand Bijou"]] | ||

[[Rebecca Jennings]] began courting interest in restoring the Lyric Theater in the early 1960s, arranging for the [[Women's Committee of 100]] to attend a special stage show emceed by [[Everett Holle]] in [[1962]]. | |||

In [[ | In [[1964]] the Women's Committee of 100 helped put together a steering committee to study the possibility of renovating the Lyric as a non-profit civic hall, and as a boost to [[Downtown revitalization|revitalization of the downtown area]]. The committee was chaired by [[Virginia Simpson]] and included [[Eleanor Bridges]], [[Virginia Samford]], [[Nancy Smith]], [[Stuart Mims]], architects [[William Vogtle]] and [[Fritz Woehle]], and playwright [[Arnold Powell]]. | ||

The Bijou lasted only a short time. | The committee developed a range of estimates, varying from $150,000 to $500,000, of how much would have to be raised. They incorporated a '''Lyric Civic Theater Association''' and hired Nashville architect Clinton E. Brush III to advise them on needed repairs and requirements for re-use. Brush advised that, "it would be financially more feasible to remodel the Lyric than to build a new building of comparable size," and suggested that the basement could be divided between dressing rooms and a "rathskeller" restaurant. Despite the committee's efforts, the project never materialized. | ||

In [[1972]], friends and old movie buffs, ''[[North Jefferson News]]'' editor [[Dee Sloan]] and x-ray technician [[Robert Whorton]] acquired the theater for a revival house showing pre-1940s pictures. They refurbished the main floor with a red and gold color scheme and new lobby furnishings, including Victorian sofas and a Czechoslovakian chandelier. They reopened as the '''Grand Bijou Motion Picture Theater''' with a screening of "The Jazz Singer", starring Al Jolson, on [[April 19]], [[1973]]. The $1.75 feature was preceded by a Keystone Kops short and a 1920s-era newsreel. | |||

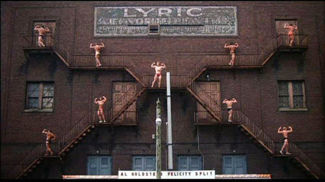

The Bijou lasted only a short time. The theater soon reopened as the '''Foxy Adult Cinema''' and later the '''Roxy Adult Cinema''', run by Water Enterprises. In [[1975]], the Lyric's twin fire escapes on [[18th Street North]] were populated by bodybuilders posing for the final scene of ''[[Stay Hungry]]''. In [[1979]] a special program of live performances was staged by a group led by [[Rebecca Jennings]] as a demonstration of the potential for rehabilitating the theater. [[Everett Holle]] emceed the program, which included [[Richard Englund]] from the [[Birmingham Civic Ballet]], [[Pam Walbert]] reading a scene from "Joan of Arc", and [[Bernadine Seay]] playing the accordion. The theater closed down for good in the early 1980s. | |||

[[Image:Lyric in Stay Hungry.jpg|left|thumb|325px|Bodybuilders pose on the Lyric's fire escape in the 1976 feature film ''Stay Hungry'']] | [[Image:Lyric in Stay Hungry.jpg|left|thumb|325px|Bodybuilders pose on the Lyric's fire escape in the 1976 feature film ''Stay Hungry'']] | ||

On [[August 31]], [[1993]], the Waters family sold the building for $10 to Birmingham Landmarks, a nonprofit organization that had taken ownership of the [[Alabama Theatre]] across the street from the Lyric a few years earlier. Although the theater itself had not been used since the 1970s, the adjoining office building housed operating retail spaces at street-level along 3rd Avenue, including [[Lyric Hot Dogs]] and [[Place Design Studio]]. The auditorium was in dire disrepair and had no climate control system, leading to further deterioration. | |||

[[Image:Lyric Theatre interior.jpg|right|thumb|275px|Interior of the theatre in 2009]] | [[Image:Lyric Theatre interior.jpg|right|thumb|275px|Interior of the theatre in 2009]] | ||

| Line 63: | Line 73: | ||

==Restoration== | ==Restoration== | ||

In [[2009]] | [[Image:Lyric_Theater_entrance,_before_and_after_renovation.jpg|left|thumb|425px|Before and after shots of the exterior renovation work. Photos by Robert Matthews.]] | ||

In [[2009]] another effort to restore the theater was launched. The City of Birmingham provided $200,000 to study the feasibility of the project, which was estimated to require approximately $16.5 million for restoration of the theater and office building. The study indicated that the redevelopment could generate as much as $3.5 million in annual economic impact. Birmingham Landmarks began a "Lyric Lobby" campaign to showcase the potential of the theater's renovation by starting work in the theater lobby. A few public open-house events were held in advance of the fundraising drive to broaden public interest in the venue. In fall [[2010]] efforts to identify hazardous materials in the building were undertaken, with the possibility of a federal brownfield grant to help fund their removal. | |||

The momentum from that effort waned and a new "campaign cabinet" was assembled to launch a renewed public outreach effort in late [[2013]]. The "Light Up The Lyric" campaign began with a goal of raising $7 million, and in mid-[[2014]] Birmingham Landmarks announced that, with $7.4 million raised, interior renovations could begin in hopes of reopening in the summer of [[2015]]. | |||

Westlake Reed Leskosky of Cleveland, Ohio collaborated with [[Davis Architects]] on the architectural design of the renovations. [[Stewart Perry Construction]] was awarded the construction management contract for the work. The main auditorium, reconfigured to seat 750, is named the "Regions Auditorium", and the lobby "Kaul Hall". | |||

The renovated Lyric Theater reopened on [[January 14]], [[2016]] with a [[2016 Lyric Theatre Moderne Vaudeville show|three-day Vaudeville-style variety show]] featuring local performers. | As work progressed, unanticipated costs arose, and the fundraisers labored to solicit donations to cover what became an $11.8 million renovation budget. That giving was supplemented by an [[Historic Preservation Tax Credit|Alabama Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit]] of $2,435,000 in [[2016]]. The completely renovated Lyric Theater reopened on [[January 14]], [[2016]] with a [[2016 Lyric Theatre Moderne Vaudeville show|three-day Vaudeville-style variety show]] featuring local performers. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* "[http://archive.org/stream/variety33-1914-01#page/n75/mode/2up Birmingham opening stopped by Hoblitzelle injunction]" (January 14, 1914) ''Variety'' - accessed December 29, 2013 | * "[http://archive.org/stream/variety33-1914-01#page/n75/mode/2up Birmingham opening stopped by Hoblitzelle injunction]" (January 14, 1914) ''Variety'' - accessed December 29, 2013 | ||

* Mandy, Charles H. (January 14, 1914) "Lyric Opening is Most Auspicious". {{BN}} | * Mandy, Charles H. (January 14, 1914) "Lyric Opening is Most Auspicious". {{BN}} | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1520 Lyric to open with pictures]" (April 24, 1932) {{BN}} - via | * "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1520 Lyric to open with pictures]" (April 24, 1932) {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1525 Lyric is Old Theater, Yet Very Modern]" (October 17, 1945) ''Birmingham Post'' - via | * "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1525 Lyric is Old Theater, Yet Very Modern]" (October 17, 1945) ''Birmingham Post'' - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1535 Lyric Theater to install screen for CinemaScope]" (September 21, 1954) {{BPH}} - via | * "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1535 Lyric Theater to install screen for CinemaScope]" (September 21, 1954) {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1536 Lyric Theater to present live musical shows]" (November 24, 1954) {{BPH}} - via | * "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1536 Lyric Theater to present live musical shows]" (November 24, 1954) {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1521 Lyric restoration boosted as architect takes look]" (June 4, 1964) {{BN}}- via | * Caldwell, Lily May (October 2, 1960) "Movies in the News" {{BN}}, p. E4 | ||

* Weaver, Emmett (June 5, 1964) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1534 Lyric Remodelling Plans Discussed]" {{BPH}} - via | * {{BPH}} (April 4, 1964) | ||

* Keith, Walling (June 22, 1964) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1522 Brighter times at Lyric]" {{BN}} - via | * "Effort To Restore Lyric For A New Civic Theatre" (April 16, 1964) {{BN}} | ||

* Haarbauer, Donald Ward (1973) ''A critical history of the non-academic theatre in Birmingham, Alabama.'' | * "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1521 Lyric restoration boosted as architect takes look]" (June 4, 1964) {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Weaver, Emmett (April 18, 1973) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1518 2 old-film buffs restore the Lyric]" {{BN}} - via | * Weaver, Emmett (June 5, 1964) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1534 Lyric Remodelling Plans Discussed]" {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Carter, Lane (April 19, 1973) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1519 Bijou opens with movie great of yesteryear]" {{BN}} - via | * Keith, Walling (June 22, 1964) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1522 Brighter times at Lyric]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Cornelius, Donna (November 8, 1978) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1538 Lyric Theatre had checkered past]. ''Metro Magazine'' - via | * "[https://cdm16044.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4017coll2/id/1524 Lyric featured Vaudeville]" (December 19, 1971) {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Weaver, Emmett (November 1979) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1537 Lyric Theater Comes To Life]" {{BPH}} - via | * Haarbauer, Donald Ward (1973) ''A critical history of the non-academic theatre in Birmingham, Alabama.'' PhD dissertation. University of Wisconsin. | ||

* Weaver, Emmett (April 18, 1973) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1518 2 old-film buffs restore the Lyric]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Carter, Lane (April 19, 1973) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1519 Bijou opens with movie great of yesteryear]" {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Cornelius, Donna (November 8, 1978) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1538 Lyric Theatre had checkered past]. ''Metro Magazine'' - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* Weaver, Emmett (November 1979) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1537 Lyric Theater Comes To Life]" {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* "A Lyrical Development." (June 1993) ''Black & White'' | * "A Lyrical Development." (June 1993) ''Black & White'' | ||

* Colburn, Sarah (June 5, 1998) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1532 Plan could make Lyric Theatre sing]." {{BPH}} - via | * Colburn, Sarah (June 5, 1998) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1532 Plan could make Lyric Theatre sing]." {{BPH}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* Hollis, Tim (August 16, 2006) "[http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/bhamtheaters_part2.htm Showplaces of the South, Part 2]." Birmingham Rewound - accessed July 10, 2008. | * Hollis, Tim (August 16, 2006) "[http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/bhamtheaters_part2.htm Showplaces of the South, Part 2]." Birmingham Rewound - accessed July 10, 2008. | ||

* Chambers, Jesse (July 3, 2008) "The voice of the theatre." ''Birmingham Weekly'' | * Chambers, Jesse (July 3, 2008) "The voice of the theatre." ''Birmingham Weekly'' | ||

* Tomberlin, Michael (January 4, 2009) "Push continues for new projects in Birmingham's theater district." {{BN}} | * Tomberlin, Michael (January 4, 2009) "Push continues for new projects in Birmingham's theater district." {{BN}} | ||

* Harvey, Alec (September 25, 2010) "Birmingham's Lyric Theatre: As films roll, curtain rises on entertainment history | * Harvey, Alec (September 25, 2010) "[https://www.al.com/scenesource/2010/09/birminghams_lyric_theatre_as_f.html Birmingham's Lyric Theatre: As films roll, curtain rises on entertainment history]" {{BN}} | ||

* Tomberlin, Michael (January 26, 2014) "Lyric Theatre exceeds $7 million fundraising goal, renovations to begin in February." {{BN}} | * Tomberlin, Michael (January 26, 2014) "Lyric Theatre exceeds $7 million fundraising goal, renovations to begin in February." {{BN}} | ||

* Davis, Bryan (June 11, 2014) "Lyric on schedule to open next summer." {{BBJ}} | * Davis, Bryan (June 11, 2014) "Lyric on schedule to open next summer." {{BBJ}} | ||

| Line 100: | Line 117: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* [http://lightupthelyric.com/ Light Up the Lyric] website | * [https://lyricbham.com/ Lyric Theatre] website | ||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20160128095344/http://lightupthelyric.com/ Archive] of the [http://lightupthelyric.com/ Light Up the Lyric] website | |||

* [http://restorethelyric.com/ Restore the Lyric] blog by Stewart Perry Construction | * [http://restorethelyric.com/ Restore the Lyric] blog by Stewart Perry Construction | ||

* [http://www.flickr.com/groups/magic_city/pool/tags/lyrictheatre/ Photos of the Lyric] in the [[Magic City Flickr Group]] | * [http://www.flickr.com/groups/magic_city/pool/tags/lyrictheatre/ Photos of the Lyric] in the [[Magic City Flickr Group]] | ||

* "[http://vimeo.com/14463725 She's a Lady]" short film, 2006 [[Digital City Films|UAB Digital City Films]] | * "[http://vimeo.com/14463725 She's a Lady]" short film, 2006 [[Digital City Films|UAB Digital City Films]] | ||

[[Category:Lyric Building| | [[Category:Lyric Theatre|*]] | ||

[[Category:Lyric Building|Theatre]] | |||

[[Category:1914 buildings]] | [[Category:1914 buildings]] | ||

[[Category:2015 buildings]] | [[Category:2015 buildings]] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:48, 14 February 2024

- This article is about the landmark theater opened in 1914 on 3rd Avenue North, for the former cinema on 2nd Avenue, see Lyric Theatre (2nd Avenue).

The Lyric Theatre is a former vaudeville and movie theater constructed in 1914 at 1800 3rd Avenue North on the corner of 18th Street North. The theater is adjoined by a Lyric Office Building, which was constructed simultaneously.

During its peak in the late 1910s and early 1920s, the Lyric hosted major touring shows under the B. F. Keith Big Time Vaudeville banner. In later years the theater was used for cinema screenings, mostly second-run and alternative releases. It is the only surviving vaudeville theater in Birmingham.

Vacant since the late 1970s, the deteriorating structure was acquired for $10 by Birmingham Landmarks in 1993. Extensive preservation and renovation efforts were renewed in 2009. The "Light Up The Lyric" campaign raised more than $8 million, allowing the auditorium to be re-opened on the 102nd anniversary of its debut, on January 14, 2016.

History

Opening

The development of the Lyric Theatre began when real-estate developer Louis V. Clark purchased three adjoining lots and hired the Hendon Hetrack Construction Company to construct a six-story office building and theater on the property. The office building is a concrete frame and the auditorium is spanned with riveted hot-rolled steel trusses.

Clark formed a partnership with Jake Wells to operate the theater. Wells already owned and managed a number of theaters across the South, including the Bijou and Orpheum Theatres, opposite each other at 3rd Avenue and 17th Street North. Wells had hired architect C. K. Howell of Richmond, Virginia, to design renovations to the Orpheum in 1912. Howell's association with the B. F. Keith circuit and with Wells in particular indicate that he was probably involved in the design of the Lyric. The interior design is also a near-identical match to the Wells Theatre which opened in 1913 in Norfolk, Virginia. That building is credited to E. C. Horn & Sons of New York, New York.

The Lyric originally had 1,583 seats spread across the main floor, two steep balconies, and two opera boxes. A center section at the front of the stage had a water tank underneath for aquatic shows (and to hold ice for a rudimentary attempt at providing air conditioning). A gold-leafed and painted asbestos curtain hung on the stage beneath a proscenium featuring a large mural known as The Allegory of the Muses, which was painted by local artist Harry Hawkins. Beneath the stage are a series of dressing rooms, each about eight feet square with sinks in the corners.

The theater's debut was set for Monday, January 12, with Wells publishing announcements that the eight B. F. Keith acts booked for the Orpheum that week would be "transferred" to the "New Lyric". As the opening approached, Wells received congratulatory telegrams from many of his peers in other cities, including Sam and Lee Shubert, William Brady, Oscar Hammerstein, George M. Cohan, A. W. Savage, Klaw & Erlanger, and John M. Slaton. The Orpheum's operator, Karl Hoblitzelle of the Interstate Company, objected and rushed to Birmingham to get a restraining order. The result was a two-day delay in opening.

It was Wednesday, January 14, 1914, then, that hosted the Lyric's debut. The acts booked for the opening performances included the Jesse Lasky company's performance of Gertrude Jennings' The Rest Cure", cartoonist Rube Goldberg, Willard and Bond, Four Bards, Claudius and Scarlet, Loraine and Dudley, Walter Van Brunt, and Archie and Gertie Falls. According to a review by Charles Mandy (who did not mention Goldberg's performance), the opening night crowd was "large, responsive, and representative of the best element of the city,", though the "girl ushers, neatly uniformed…proved very acceptable…the crowd made the addition of one or two 'boys' necessary."

Originally the theater offered a program of seven different acts each week, with three nightly performances and matinees on Saturday. The Four Marx Brothers brought a company of 16 to headline a program on Thanksgiving Day, November 26, 1914.

Heyday

In its heyday, the theater was operated jointly by Wells and Karl Hoblitzelle, who had bought a share in the business and brought acts from his Interstate Amusement Company. Their disagreements brought frequent turmoil to the theater. After a sudden closure in early 1915, the former Vaudeville house reopened with a less-prestigious "Three-A-Day" variety program. Soon after, even that format was dropped and the stage began hosting continuous run programs with a house repertory company. The crisis was averted when the rival Jefferson Theatre ran into financial troubles and the Lyric once again assumed the mantle of the city's premier Vaudeville hall.

"The Lyric Company" with Hoblitzelle as president, secured affiliations with the Orpheum Circuit, B. F. Keith's circuit, United Booking Offices of America, and the Western Vaudeville Manager's Association as well as his own Interstate Amusement Company. Stars such as Sophie Tucker, Gus Edward's Kid Kabaret with George Jessel and Eddie Cantor, Will Rogers, the Keaton Family Acrobats (with Buster Keaton), Milton Berle, Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Belle Baker, the Marx Brothers, Lottie Mayer's "Neptune Gardens" water divers, Marshall Montgomery, Pat Rooney and Marion Bent, and Mae West appeared on stage.

W. S. Crosbie was the local manager in charge, with Al Plante as musical director of the Lyric Wonder Orchestra. Daily performances were scheduled for 2:30, 7:15 and 9:10, with two matinees (1:15 and 3:15) on Saturdays. Under Hoblitzelle's orders, all performances were guaranteed to be free of offensive words, expressions and situations. With shows prohibited on Sundays, the Lyric hosted sermons by Independent Presbyterian Church pastor Henry Edmonds at 8:00 PM each week. After motion pictures became popular, the Lyric pared its live schedule down to five new acts per week.

In the early 1920s the Lyric started to see more competition. The Masonic Temple Theater was completed in 1922 and the Ritz and Empire Theaters opened in 1926. The Keith circuit continued to bring weekly touring acts to the Lyric, with Pathé newsreels and Fox Film Corp. comedies screened before the stage show.

After the completion of the larger air-conditioned Ritz, the Lyric permanently lost its status the grandest Vaudeville hall in Birmingham. One of its last major shows was the Birmingham premiere of "Men of Steel", a silent feature that had been filmed in Ensley, accompanied by an "augmented orchestra". Bob O'Donnell of the Interstate Amusement Company reported to the distributor that it was breaking every record for receipts with standing room only from 2:00 PM until closing with immediate plans to hold the picture over for a second week.

On Sunday evenings the theatre was used by the newly-formed Independent Presbyterian Church. A Kilgen opus 3459 size 2/4 theater organ was installed in 1925. The touring "A. B. Marcus Revue" held court at the Lyric in 1926 with a large cast and chorus line. The Lyric hosted its own stock dramatic troupes in the off-season, including one with John McFarland and Katherine Comeges as its stars. Russell Filmore's Favorite Players with Jerome Cowan took to the stage with their popular light comedy from 1927 to 1930.

Decline

The Lyric continued to operate successfully up until the Great Depression. With his funds overextended, Wells lost his chain of theaters and ultimately committed suicide. Ownership of the Lyric reverted to the mortgage company which leased it to the Shubert organization. The Lyric continued to present vaudeville acts, but the Depression and competition from movies and radio led to its decline and closure in 1930 or 1931.

In 1932, brothers Ben and L. A. Stein of Jacksonville, Florida reopened the Lyric as a movie theater. They installed a new Western Electric sound system and other refurbishments and scheduled four feature films each week, beginning with Will Rogers in "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" on April 25 of that year. Ben returned to Florida while his brother remained in Birmingham as manager. Later the same year it was leased to the Paramount and the Wilby-Kincey circuit to operate it as a second run theater, often showing movies that had their local premieres across the street at the Alabama.

In October 1932, the Communist Party USA District 17 hosted a rally for the 1932 general election at the Lyric. Scheduled speaker Clarence Hathaway did not appear because of his arrest the previous night in New Orleans, Louisiana. In his stead Fred Keith spoke on issues relating to the election, the party's Unemployed Workers Movement, and the trial of the Scottsboro boys. The meeting was interrupted by a smoke bomb tossed into the auditorium by a Ku Klux Klan member.

The Lyric received another major renovation with new projection equipment in the early 1940s while Oliver Naylor was manager. In June 1945 Ervin Jackson & Associates bought the Lyric out of foreclosure for $400,000. They extended its lease it to the Waters Theater Company, headed by Newman Waters, Sr. which continued its association with Paramount as a second-run house. In 1950 Waters turned the lease over to the Acme Theatres chain which also operated the Melba Theater, Empire Theater, Galax Theater and Royal Theater.

The opera boxes were removed in 1954 under Bill O'Neill's tenure as manager in order to accommodate a 15' tall by 36' wide screen for CinemaScope films. O'Neill also brought back live performances, with a weekly 11 PM "Saturday Night Jamboree" hosted by "Uncle" Jim Atkins and broadcast live on WBRC-AM. Among the musicians taking the stage in the 1950s were Gene Autry and Roy Rogers.

Henry Hury took over management for Acme some time later. The theater closed its doors again when the exhibitor lost its lease. The last day of operation was Sunday, October 2, 1960. The adjoining office building remained active with businesses such as the House of $8.50 Eyeglasses. Congress of Racial Equality photographer Bob Adelman documented the leftover "Colored Balcony" sign on 18th Street North in 1963.

Later life

Rebecca Jennings began courting interest in restoring the Lyric Theater in the early 1960s, arranging for the Women's Committee of 100 to attend a special stage show emceed by Everett Holle in 1962.

In 1964 the Women's Committee of 100 helped put together a steering committee to study the possibility of renovating the Lyric as a non-profit civic hall, and as a boost to revitalization of the downtown area. The committee was chaired by Virginia Simpson and included Eleanor Bridges, Virginia Samford, Nancy Smith, Stuart Mims, architects William Vogtle and Fritz Woehle, and playwright Arnold Powell.

The committee developed a range of estimates, varying from $150,000 to $500,000, of how much would have to be raised. They incorporated a Lyric Civic Theater Association and hired Nashville architect Clinton E. Brush III to advise them on needed repairs and requirements for re-use. Brush advised that, "it would be financially more feasible to remodel the Lyric than to build a new building of comparable size," and suggested that the basement could be divided between dressing rooms and a "rathskeller" restaurant. Despite the committee's efforts, the project never materialized.

In 1972, friends and old movie buffs, North Jefferson News editor Dee Sloan and x-ray technician Robert Whorton acquired the theater for a revival house showing pre-1940s pictures. They refurbished the main floor with a red and gold color scheme and new lobby furnishings, including Victorian sofas and a Czechoslovakian chandelier. They reopened as the Grand Bijou Motion Picture Theater with a screening of "The Jazz Singer", starring Al Jolson, on April 19, 1973. The $1.75 feature was preceded by a Keystone Kops short and a 1920s-era newsreel.

The Bijou lasted only a short time. The theater soon reopened as the Foxy Adult Cinema and later the Roxy Adult Cinema, run by Water Enterprises. In 1975, the Lyric's twin fire escapes on 18th Street North were populated by bodybuilders posing for the final scene of Stay Hungry. In 1979 a special program of live performances was staged by a group led by Rebecca Jennings as a demonstration of the potential for rehabilitating the theater. Everett Holle emceed the program, which included Richard Englund from the Birmingham Civic Ballet, Pam Walbert reading a scene from "Joan of Arc", and Bernadine Seay playing the accordion. The theater closed down for good in the early 1980s.

On August 31, 1993, the Waters family sold the building for $10 to Birmingham Landmarks, a nonprofit organization that had taken ownership of the Alabama Theatre across the street from the Lyric a few years earlier. Although the theater itself had not been used since the 1970s, the adjoining office building housed operating retail spaces at street-level along 3rd Avenue, including Lyric Hot Dogs and Place Design Studio. The auditorium was in dire disrepair and had no climate control system, leading to further deterioration.

In 1998 the Birmingham Art Association opened a gallery in the theater's office building while the Metropolitan Arts Council worked on plans to restore and reopen the entire facility for $10 million as a community arts center. The plans were part of the $600 million Metropolitan Area Project Strategy (MAPS) proposal which was defeated in a county-wide public referendum. $2.5 million of the anticipated restoration cost was raised privately, but the failure of MAPS put the project on hold.

Restoration

In 2009 another effort to restore the theater was launched. The City of Birmingham provided $200,000 to study the feasibility of the project, which was estimated to require approximately $16.5 million for restoration of the theater and office building. The study indicated that the redevelopment could generate as much as $3.5 million in annual economic impact. Birmingham Landmarks began a "Lyric Lobby" campaign to showcase the potential of the theater's renovation by starting work in the theater lobby. A few public open-house events were held in advance of the fundraising drive to broaden public interest in the venue. In fall 2010 efforts to identify hazardous materials in the building were undertaken, with the possibility of a federal brownfield grant to help fund their removal.

The momentum from that effort waned and a new "campaign cabinet" was assembled to launch a renewed public outreach effort in late 2013. The "Light Up The Lyric" campaign began with a goal of raising $7 million, and in mid-2014 Birmingham Landmarks announced that, with $7.4 million raised, interior renovations could begin in hopes of reopening in the summer of 2015.

Westlake Reed Leskosky of Cleveland, Ohio collaborated with Davis Architects on the architectural design of the renovations. Stewart Perry Construction was awarded the construction management contract for the work. The main auditorium, reconfigured to seat 750, is named the "Regions Auditorium", and the lobby "Kaul Hall".

As work progressed, unanticipated costs arose, and the fundraisers labored to solicit donations to cover what became an $11.8 million renovation budget. That giving was supplemented by an Alabama Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit of $2,435,000 in 2016. The completely renovated Lyric Theater reopened on January 14, 2016 with a three-day Vaudeville-style variety show featuring local performers.

References

- "Birmingham opening stopped by Hoblitzelle injunction" (January 14, 1914) Variety - accessed December 29, 2013

- Mandy, Charles H. (January 14, 1914) "Lyric Opening is Most Auspicious". The Birmingham News

- "Lyric to open with pictures" (April 24, 1932) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Lyric is Old Theater, Yet Very Modern" (October 17, 1945) Birmingham Post - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Lyric Theater to install screen for CinemaScope" (September 21, 1954) Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Lyric Theater to present live musical shows" (November 24, 1954) Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Caldwell, Lily May (October 2, 1960) "Movies in the News" The Birmingham News, p. E4

- Birmingham Post-Herald (April 4, 1964)

- "Effort To Restore Lyric For A New Civic Theatre" (April 16, 1964) The Birmingham News

- "Lyric restoration boosted as architect takes look" (June 4, 1964) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Weaver, Emmett (June 5, 1964) "Lyric Remodelling Plans Discussed" Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Keith, Walling (June 22, 1964) "Brighter times at Lyric" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Lyric featured Vaudeville" (December 19, 1971) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Haarbauer, Donald Ward (1973) A critical history of the non-academic theatre in Birmingham, Alabama. PhD dissertation. University of Wisconsin.

- Weaver, Emmett (April 18, 1973) "2 old-film buffs restore the Lyric" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Carter, Lane (April 19, 1973) "Bijou opens with movie great of yesteryear" The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Cornelius, Donna (November 8, 1978) "Lyric Theatre had checkered past. Metro Magazine - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Weaver, Emmett (November 1979) "Lyric Theater Comes To Life" Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "A Lyrical Development." (June 1993) Black & White

- Colburn, Sarah (June 5, 1998) "Plan could make Lyric Theatre sing." Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Hollis, Tim (August 16, 2006) "Showplaces of the South, Part 2." Birmingham Rewound - accessed July 10, 2008.

- Chambers, Jesse (July 3, 2008) "The voice of the theatre." Birmingham Weekly

- Tomberlin, Michael (January 4, 2009) "Push continues for new projects in Birmingham's theater district." The Birmingham News

- Harvey, Alec (September 25, 2010) "Birmingham's Lyric Theatre: As films roll, curtain rises on entertainment history" The Birmingham News

- Tomberlin, Michael (January 26, 2014) "Lyric Theatre exceeds $7 million fundraising goal, renovations to begin in February." The Birmingham News

- Davis, Bryan (June 11, 2014) "Lyric on schedule to open next summer." Birmingham Business Journal

- Stewart, Merrill (n. d.) "Frozen in Time: Structural Analysis in a Historical Renovation" Planting Acorns weblog. Stewart Perry Construction

- Archibald, John (October 18, 2015) "'Best theater in America' tunes to reopen in Alabama." The Birmingham News

- Colurso, Mary (December 1, 2015) "Birmingham's Lyric Theatre to open in January with 3 vaudeville shows, followed by concert series." The Birmingham News

- Huebner, Michael (December 9, 2015) "Power of compromise: Lyric Theatre’s detours leading to auspicious rebirth" ArtsBham.com

- Chambers, Jesse (January 1, 2016) "Miracle on Third Avenue" B-Metro

- Colurso, Mary (January 13, 2016) "How the historic Lyric Theatre was saved: 'Beautiful ruin' gets glittering rebirth." The Birmingham News

External links

- Lyric Theatre website

- Archive of the Light Up the Lyric website

- Restore the Lyric blog by Stewart Perry Construction

- Photos of the Lyric in the Magic City Flickr Group

- "She's a Lady" short film, 2006 UAB Digital City Films