Linn Park

- This article is about the current downtown park. For the first park in Birmingham, see Linn's Park. There is also a Lynn Park in East Lake.

Charles Linn Park (formerly Central Park, Capitol Park, and Woodrow Wilson Park) anchors the municipal center of downtown Birmingham. It occupies Block 21, a 610-foot by 400-foot block bounded by 20th Street North and the Birmingham City Hall to the west, Park Place to the south, 8th Avenue North, with Boutwell Auditorium and the Birmingham Museum of Art to the north, and the Linn-Henley Research Library and the Jefferson County Courthouse to the east.

As Birmingham's primary civic space, Linn Park contains numerous monuments and memorials, and hosts several public events such as the Birmingham Christmas tree lighting ceremony, the Magic City Art Connection, Magic City Blues Fest and other gatherings. It was also the home of the City Stages music festival held from 1989 to 2009.

History

The site was one of three parks included in the Elyton Land Company's original plans for Birmingham, as drafted by William Barker. Labeled "Park" on the original plat, it came to be called "Central Park" as it crowned the central spine of 20th Street and lay midway between "East Park" (now Marconi Park) and "West Park" (now Kelly Ingram Park).

On February 21, 1883, in exchange for $90, Elyton Company president Henry Caldwell handed over the deeds to those three parks to Mayor A. O. Lane, on the condition that the city also reimburse the company for the cost of a newly-installed iron fence and for the costs associated with the conveyance, fund public improvements to the property immediately, and agree to relinquish the site to the State should the city succeed in having the capital moved to Birmingham from Montgomery.

In 1886 James Powell inserted the name "Capitol Park" into a map being produced by Beers, Ellis and Company for the "Atlas of the City of Birmingham and Suburbs". The map, published in 1887, showed a conjectured T-shaped building just south of the park's center as a stand-in for a future capitol building. Though Governor Joseph Johnston briefly conducted state business from a rented store in the city during a yellow fever outbreak in Montgomery, no other steps toward relocating the capital from Montgomery were ever accomplished.

By the time the Beers map was printed, the lots surrounding the park were built up with large fashionable houses, many in the ornate and complex Queen Anne style with effusions of brightly-painted wood porches, balconies, turrets, oriels, gables and bays.

Monuments

A large cast-iron fountain, donated to the city in the 1880s by T. L. Hudgins, was moved to the park in 1891. An obelisk-style Confederate Soldiers & Sailors Monument was erected between 1894 and 1905 at the park's southern end. In 1904 and 1908 two monuments sculpted by GIuseppi Moretti were dedicated at Capitol Park, the first to physician William Elias B. Davis and the second to school teacher Mary Cahalan. The city constructed various curvilinear sidewalks connecting to those points of interest and planted trees between them.

The rather haphazard result was described thus by visitor Julian Street in 1917:

"[N]ot far from the majestic Tutwiler Hotel, and the imposing apartment building called the Ridgely, the front of which occupies a full block, is a park so ill kept that it would be a disgrace to the city but for the obvious fact that the city is growing and wide-awake, and will, of course, attend to the park when it can find the time. Here are, I believe, the only public monuments Birmingham contains. One is a Confederate monument in the form of an obelisk, and the other two are statues erected in memory of Mary A. Cahalan, for many years principal of the Powell School, and of William Elias B. Davis, a distinguished surgeon. Workers in these fields are too seldom honored in this way, and the spirit which prompted the erection of these monuments is particularly creditable; sad to say, however, both effigies are wretchedly placed and are in themselves exceedingly poor things. Art is something, indeed, about which Birmingham has much to learn.

On December 3, 1918 the park was officially renamed for Woodrow Wilson, then in his second term as President and the spokesman of the terms of peace following World War I. The honor was likely bestowed in combined admiration for his handling of the war and its conclusion, as well as for his Democratic party alliegiance. Specifically he supported the Southern Democrats who were increasingly concerned about Federal interference in the enforcement of Jim Crow laws requiring racial segregation. The Commisison then in power was headed by nativist Nathaniel Barrett, who rode the support of the "True Americans" into office in 1917. The new name was not always recognized. in his "Love Story of Vulcan and Electra", published in the Birmingham Post in 1921, Dr. B. U. L. Conner continued to use the name "Capitol Park".

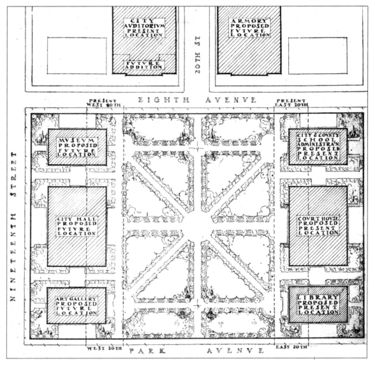

The "City Plan of Birmingham", commissioned from Warren Manning in 1914 by George Ward's City Commission, was finally published in 1919. The plan, which was never adopted, did include a "Civic Center Memorial" scheme, largely the work of local associate Frank Hartley Anderson. The "City Beautiful"-type proposal, like others inspired by the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893, imagined a group of neo-classical buildings in a heroic scale arrayed symmetrically around the park's open space. A central pole would fly the "flag of freedom" and a 450-foot floodlit "Memorial Tower" would hold aloft a bright beacon which could be used to signal important news to the entire city, presumably by Morse code. Manning, himself, was skeptical of the civic center idea. Nevertheless, it was published alongside his comprehensive regional plan, and was perhaps the most nearly-realized of the plan's recommendations.

Anderson, working with local architects William Warren and Eugene Knight, elaborated on the Civic Center idea with a plan published in the Birmingham News in 1921. Perhaps betraying the interests of Robert Jemison Jr, the plan placed the 1913 Ridgely Apartments at a prominent corner of the park, which would be extended to 6th Avenue North. The north end of the park would house a City Hall and Court House, with a massive 450-foot "Memorial Tower" occupying a "Court D'Honneur" between them. The park itself was indicated with parterres and automobile lots, with a 110-foot flagpole in the center and the existing Confederate monument pushed southward to anchor its southern end. Hill Ferguson, then an associate of Jemison's, pushed hard for the realization of the plan and succeeded in securing the endorsements of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce and the Birmingham Real Estate Exchange. He was also successful in lobbying the city to purchase property around the park.

The publication of the Manning plan coincided with the Chamber of Commerce's proposal for a Municipal Auditorium. A bond sale for the purpose of building such a structure passed in 1918. By the time construction began in 1924 a site at the northwestern corner of Wilson Park had been selected and secured. A World War I memorial, donated to the American Legion, Birmingham Post No. 1 by the city's Greek-American citizens, was displayed prominently at the front entrance.

Civic Center plans

Landscape architect W. B. Marquis visited the city in July 1924 on behalf of the Olmsted Brothers, who had been commissioned by the Birmingham Board of Parks and Recreation to prepare a comprehensive plan for "A Park System for Birmingham." Marquis' report on Capitol Park [sic] noted that it was "very probable that it will become the center of a group of civic buildings." He continued:

As one approaches from the south, the profile of 20th St. is very pleasant and and is almost equally so as one approaches from the north. It seems rather obvious that this park should be developed as formally as possible taking into consideration the existing trees, some of which are very good. There is very little else of value in it. The Confederate Monument located on the axis of 20th St. at the south end of the park probably must be retained although there may be some possibility of changing its position. There are three other monuments, one of a Doctor, one to the soldiers of the late war, erected by the American Legion, and another of a well-known school teacher…The Confederate Monument is not unpleasant in design but the other three are all mediocre.

Marquis mentions hope expressed by parks superintendent Charles Connell that the Mary Cahalan statue could be moved onto the grounds of the Powell School. That August, Miller & Martin architects, working on a design for the Jefferson County Courthouse, advised Connell that in their present scheme, they would relocate the Confederate Monument to one end of a terrace in front of the new building, with a War Monument to balance it on the other end.

With the auditorium under construction, a revised Civic Center plan, attributed to Mel Drennen and Erskine Ramsay and probably delineated by William Welton, appeared in the September 28, 1924 edition of the Birmingham News. This plan indicated the auditorium site and was the first to show the proposed locations for the Birmingham Public Library, Jefferson County Courthouse, and Birmingham City Hall as they were effected in 1927, 1931 and 1950, respectively. The library board had hoped to build closer to the center of the park and only reluctantly accepted relegation to a corner after the Olmsted Brothers, then engaged in a plan for A Park System for Birmingham, ruled in favor of preserving the open space. A compromise solution, requiring the abandonment of East 20th Street, was accepted. The specific sites indicated for an armory, museum, art gallery, and school administration building were not used, although the Birmingham Museum of Art (1959) and Birmingham Board of Education Building (1965) were constructed later on other sites facing the park.

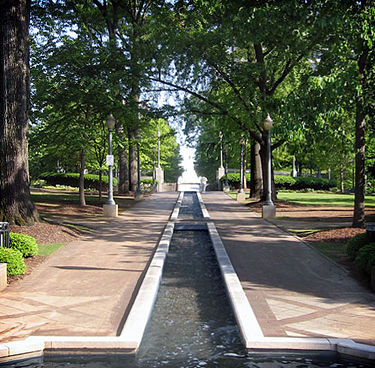

Along with the construction of the Courthouse in 1926-1931, landscape architect William Kessler provided designs for improvements to the park which were executed by Works Progress Administration crews. Kessler's scheme introduced broad axial paths dividing the park into quadrants. The east-west axis was marked with four reflecting pools between the center cross-axis and the courthouse. Large flower beds on terraces stepped down toward Short 20th Street.

Several new large trees were planted in the park at that time. Most of the new arrivals were elms, but one of them, a large Gingko on the western side of the park, stood as a "representative of the world's oldest species of trees." A March 10, 1932 Birmingham Post account of the plantings noted that, "Because of the lack of space, it was not possible to lay out these trees in a symmetrical design, but they have been placed in the most advantageous points possible."

A marble Zero mile marker was also placed in the park by the Alabama Motorists Association in 1927, signifying the point from which distances to Birmingham were calculated.

Mid-century developments

The block west of Short 20th Street finally became the site for a new Birmingham City Hall which opened in 1950. That same year, the Boy Scouts' Birmingham Area Council donated "To Strengthen the Arm of Liberty", a pressed copper replica of the Statue of Liberty, which was displayed on a limestone plinth in the central reflecting pool. In 1963 a proposal for a "Venus fountain" was made, but never realized.

Several magnolia trees, donated by a nursery, were used to line the 7th Avenue and Short 20th Street edges of the park.

Over the years the planting bed closest to City Hall has been used to create a "Floral Map of Alabama" depicting the outline of the state with its major rivers and cities planted with contrasting-color flowers.

1980s renovation

In 1982 the "Friends of Woodrow Wilson Park" began raising funds for renovations and improvements in the park. Landscape architects Nimrod Long & Associates preserved and enhanced Kessler's axial scheme with a new central fountain, pavements, benches, steps, low walls, and a metal gazebo. In 1985 the project was budgeted at $1.5 million, of which $600,000 was set aside by the city, $400,000 by Jefferson County, and $250,000 raised through private donations. Tentative plans then included a concert stage and six pushcarts to be rented by food vendors. Ultimately, the project cost was increased to $2.5 million, split between private donations and public funds. Brasfield & Gorrie served as general contractor. When the park was rededicated on October 4, 1988, it was renamed again to honor Charles Linn. Linn was a pioneer industrialist and banker, who created the first landscaped park in the city and promoted the planting of trees to beautify 20th Street. A statue of Linn was added to the park in 2013.

In 2015 the city ended the practice of waiving fees for public services related to events held at the park. The Magic City Art Connection, notified of the policy change only weeks in advance, began charging a $5 admission for adults.

Linn Park, specifically the Confederate Memorial, became a target for vandalism during the 2020 George Floyd protests. On the evening of May 31 a large group, many of whom had attended an earlier protest at Kelly Ingram Park, answered a call by speaker Jermaine Johnson to meet him at Linn Park to take down the memorial. Efforts to topple the 52-foot obelisk using hand tools and rope tied to a pick-up truck failed and some, prepared with spray paint and crowbars, turned their attention to the statue of Linn, who had attempted to run blockades on behalf of the Confederacy before becoming a banker and investor in Birmingham. The Spirit of the American Doughboy statue and the Thomas Jefferson statue in the park were also damaged before Mayor Randall Woodfin arrived at the scene and asked the crowd to disperse, promising to remove the Confederate Memorial himself within 24 hours. In fact Woodfin made good on that promise as crews arrived the next night to dismantle and haul away the monument.

In early August activist Frank Matthews made a public call to the Birmingham Parks & Recreation Board to rename the park in honor of Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights founder Fred Shuttlesworth and the late John Lewis, a Troy native and veteran of the Civil Rights Movement who was serving his 17th term in the U.S. House of Representatives when he died on July 17, 2020. The board voted unanimously to proceed with the suggestion during their August 7 meeting.

2020s Re-Visioning

In 2022 REV Birmingham began convening for a "Re-Visioning" process, using $350,000 in funds provided by the Friends of Linn Park and the Philip Morris Fund for Design Arts at the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham. OJB Landscape Architecture of Houston, Texas and Trahan Architects of New Orleans, Louisiana were hired to collect community input in collaboration with CBG Strategies, Macknally Land Design, and KHAFRA civil engineers. Other community partners included the Birmingham Park and Recreation Board, the Mayor's Office of Social Justice and Racial Equity, and the Birmingham Museum of Art. Kelleigh Gamble and Anne Rygiel, co-chairs of the Neighborhood Housing and Homelessness subcommittee of Mayor Randall Woodfin's transition team, also participated in the process.

After a public workshops and several surveys, Re-Vision Linn Park arrived at a short list of desired amenities for the park, including community space, a shade structure, a park café, and children's play area. A setting for Equal Justice Initiative's Jefferson County Memorial to lynching victims was also part of the program. The team prepared three design concepts for further discussion, which was combined into a single proposal revealed on October 4.

See Also

Gallery

William Elias B. Davis statue in 1905

1957 rendering of the Oscar Wells Memorial Building

"To Strengthen the Arm of Liberty" statue in the late 1970s

Reflecting pool with "To Strengthen the Arm of Liberty" statue in the late 1970s

Birmingham Christmas Tree in 2005

Charles Linn statue in 2014

Nina Miglionico statue in 2018

References

- Street, Julian (1917) American Adventures: A Second Trip "Abroad at Home" New York: The Century Co.

- "Woodrow Wilson Park, Central & Capitol" unsigned typescript (n.d.) from the collection of M. R. Henckell - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Garret, Harry (June 25, 1947) "Woodrow Wilson Park, Purchased For $30, Scene Of Many Events Through The Years" Birmingham Post - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Flower Lecture Proceeds Will Beautify City" (December 4, 1949) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "3 parks 'given' to city are now worth $2 million" (August 18, 1958) Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Buchanan, John (July 16, 1968) "Birmingham's 15th Annual Independence Day Celebration." The Congressional Record, 90th Congress. 2nd Session. Vol. 114, Part 16, p. 21642

- White, Marjorie Longenecker, ed. (1980) Downtown Birmingham: Architectural and Historical Walking Tour Guide, second edition. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society

- Ellis, Holly (February 1985) "Money pushes park plans closer to goal." Magic City News, Vol. 2, No. 5

- Reuse, Ruth (September 1985) "Old, new trees dot city streets" Magic City News, Vol. 2, No. 12

- Campbell, Cathryn S. "A History of Central - Capitol - Woodrow Wilson - Linn Park" in Morris, Philip A. and Marjorie Longenecker White, eds. (1989) Designs on Birmingham: A Landscape History of a Southern City and Its Suburbs Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society

- Hand Down Unharmed: Olmsted Files on Birmingham Parks 1920-1925 (2008) Birmingham Historical Society. ISBN 0943994322

- Shelby, Thomas Mark (2009) D. O. Whilldin: Alabama Architect. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society ISBN 0943994330

- Fazio, Michael W. (2010) Landscape of Transformations: Architecture and Birmingham, Alabama. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 9781572336872

- Beahm, Anna (August 7, 2020) "Birmingham’s Linn Park could honor civil rights leaders after board OK." The Birmingham News

- Jefferson County Memorial Project (2021) Contested Terrain: A Historical Walk Through Birmingham's Linn Park"

- Robinson, Carol (July 21, 2021) "1 person suffers minor injuries when tree falls in Linn Park." The Birmingham News

- Parker, Illyshia (May 10, 2022) "Planning and design for Re-Vision Linn Park is underway." Birmingham Business Journal

- Parker, Illyshia (September 28, 2022) "Renderings reveal potential plans for Linn Park." Birmingham Business Journal

- Garrison, Greg (October 4, 2022) "Birmingham will mow Linn Park with robots." The Birmingham News